At a July fundraising event in Chicago, Mrs. Michelle Obama remarked, “So, yeah, there’s too much money in politics. There’s (sic) special interests that have too much influence.” Sen. John McCain has been complaining for years that “there is too much money washing around political campaigns today.” According to a 2012 Reuters poll, “Seventy-five percent of Americans feel there is too much money in politics.” Let’s think about money in politics, but first a few facts.

During the 2012 presidential campaign, Barack Obama raised a little over $1 billion, while Mitt Romney raised a little under $1 billion. Congressional candidates raised over $3.5 billion. In 2013, there were 12,341 registered lobbyists and $3.2 billion was spent on lobbying. During the years the Clintons have been in national politics, they’ve received at least $1.4 billion in contributions, according to Time magazine and the Center for Responsive Politics, making them “The First Family of Fundraising.”

Here are my questions to you: Why do people and organizations cough up billions of dollars to line political coffers? One might answer that these groups and individuals are simply extraordinarily civic-minded Americans who have a deep and abiding interest in encouraging elected officials to live up to their oath of office to uphold and defend the U.S. Constitution. Another possible answer is that the people who spend these billions of dollars on politicians just love participating in the political process. If you believe either of these explanations for coughing up billions for politicians, you’re probably a candidate for psychiatric attention, a straitjacket and a padded cell.

A far better explanation for the billions going to the campaign coffers of Washington politicians and lobbyists lies in the awesome government power and control over business, property, employment and other areas of our lives. Having such power, Washington politicians are in the position to grant special privileges, extend favors, change laws and do other things that if done by a private person would land him in jail. The major component of congressional power is the use of the IRS to take the earnings of one American to give to another.

The Dow Chemical Co. posted record lobbying expenditures last year, spending over $12 million. Joined by Alcoa, who spent $3.5 million, Dow supports the campaigns of congressmen who support natural gas export restrictions. Natural gas is a raw material for both companies. They fear natural gas prices would rise if export restrictions were lifted. Dow and other big users of natural gas make charitable contributions to environmentalists who seek to limit natural gas exploration. Natural gas export restrictions empower Russia’s Vladimir Putin by making Europeans more dependent on Russian natural gas.

General Electric spends tens of millions of dollars lobbying. Part of their agenda was to help get Congress to outlaw incandescent light bulbs so that they could sell their more expensive compact fluorescent bulbs. It should come as no surprise that General Electric is a contributor to global warmers who helped convince Congress that incandescent bulbs were destroying the planet.

These are just two examples, among thousands, of the role of money in politics. Most concerns about money in politics tend to focus on relatively trivial matters such as the costs of running for office and interest-group influence on Congress and the White House. The bedrock problem is the awesome power of Congress. We Americans have asked, demanded and allowed congressmen to ignore their oaths of office and ignore the constitutional limitations imposed on them. The greater the congressional power to give handouts and grant favors and make special privileges the greater the value of being able to influence congressional decision-making. There’s no better influence than money.

You say, “Williams, you’ve explained the problem. What’s your solution?” Maybe we should think about enacting a law mandating that Congress cannot do for one American what it does not do for all Americans. For example, if Congress creates a monopoly for one American, it should create a monopoly for all Americans. Of course, a better solution is for Congress to obey our Constitution.

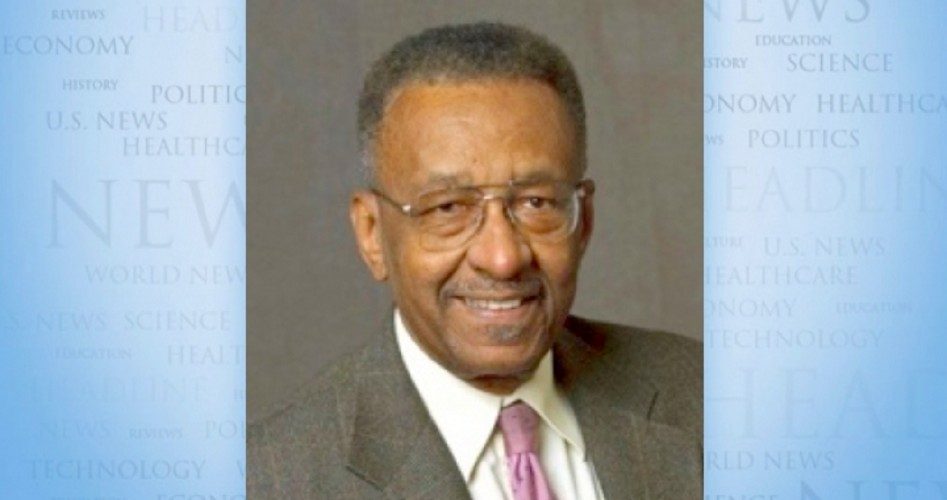

Walter E. Williams is a professor of economics at George Mason University. To find out more about Walter E. Williams and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate Web page at www.creators.com.

COPYRIGHT 2014 CREATORS.COM