Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke’s promise not only to expand the money supply by buying more mortgage-backed securities but to continue doing so until he sees “ongoing sustained improvement in the labor market” has sparked numerous warnings of unintended consequences as a result. The Federal Open Market Committee said on September 13:

If the outlook for the labor market does not improve substantially, the committee will continue its purchases of agency mortgage-backed securities, undertake additional asset purchases, and employ its other policy tools as appropriate until such improvement is achieved in a context of price stability.

One of the people who is most nervous about the Fed’s plan to continue to print until the recovery begins in earnest is Martin Feldstein, former chairman of President Ronald Reagan’s Council of Economic Advisors. Writing in The Financial Times newspaper, Feldstein called Bernanke’s idea a “dangerous” strategy which could lead to high inflation and asset bubbles while waiting for that recovery to begin.

A chart from the Federal Reserve showing just how much new paper money the Federal Reserve has already pumped into the economy in its attempt to jump-start it is unnerving. As recently as 1990, the Fed’s balance sheet was a monstrous $350 billion. Currently it is $2.6 trillion, more than a seven-fold increase. Even children know that when the supply of something increases, each piece is worth less.

At present, however, that new money is residing on the balance sheets of the Fed’s member banks rather than being spun out into the economy. For the moment, that is. Another chart from the Fed shows just how unwilling banks are to lend, and borrowers to borrow, the new money. Turnover of money in the economy before the Great Recession averaged 1.6 (meaning that one dollar in the economy was “turned over” or spent about one-and-a-half times every year). That ratio dropped to a low of 0.7 during the current recession and is still less than 1.0, enough to keep inflation fires under control, for the moment.

Unfortunately, the “trigger” that will ignite spending the new money is obscure. Harry Figgie, in his blockbuster book Bankruptcy 1995, said three things had to be in place before the average citizen finally figured out that it was better to spend his cash rather than hoard it:

1. The federal government can no longer collect enough tax revenue to service its debt.

2. The Federal Reserve begins to buy substantial amounts of the government’s debt.

3. Congress and the administration, while they talk a good game, avoid taking the bold actions needed to bring down the deficit.

One can see that it’s just a matter of time before all three of these conditions are met. No wonder Feldstein is nervous.

In addition, Feldstein is nervous about an “asset bubble” as a result of the continuing Fed actions. Looking around, the most apparent bubble is in the price of bonds, especially long or long-maturity 30-year bonds. As interest rates have dropped from the early 1980s to the present, bond values have jumped. Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business warned back in March that the end of the 30-year bull market in bond prices is over.

As their article acknowledged, “A basket of stocks would have returned a mere 19% from the start of 2000 through 2011, for example, while a basket of bonds would have returned about 113%….”

But now that interest rates have reached historic lows, the only direction from here is up. As Wharton points out, for every one percent rise in interest rates the holder of a 30-year bond will lose 10 percent of his value, and acknowledges that “bonds — and bond funds — are riskier than they have been in recent decades.”

Waiting for the economy to improve before turning off the printing presses is likely to take a very long time. The August numbers on the economy were disheartening for those waiting for such an improvement: U.S. durable goods production fell for the third month in a row, astonishing economists who had predicted much better numbers. GDP continues to slow, and companies such as Caterpillar, the world’s biggest construction and mining equipment manufacturer, cut its earnings outlook because of the continuing slowdown in the world economy.

And jobs? The 96,000 jobs added last month not only were significantly fewer than economists had predicted, they were far below the number necessary to absorb new entrants into the workforce, forcing many people to withdraw altogether from even looking for work. The unemployment rate has remained above eight percent for 43 months, the longest period since records began in 1948, and it would be over nine percent if the workforce itself hadn’t shrunk due to discouraged job seekers giving up.

But the Fed is determined to continue to do the only thing it knows how to do: expand the money supply, buy up additional securities, put newly created money into the hands of its member banks, and hope. Hope that someday, somehow, miraculously, consumers will start to spend again.

It’s a forlorn hope, and likely to be a long wait. In the meantime, the Fed continues to play with fire.

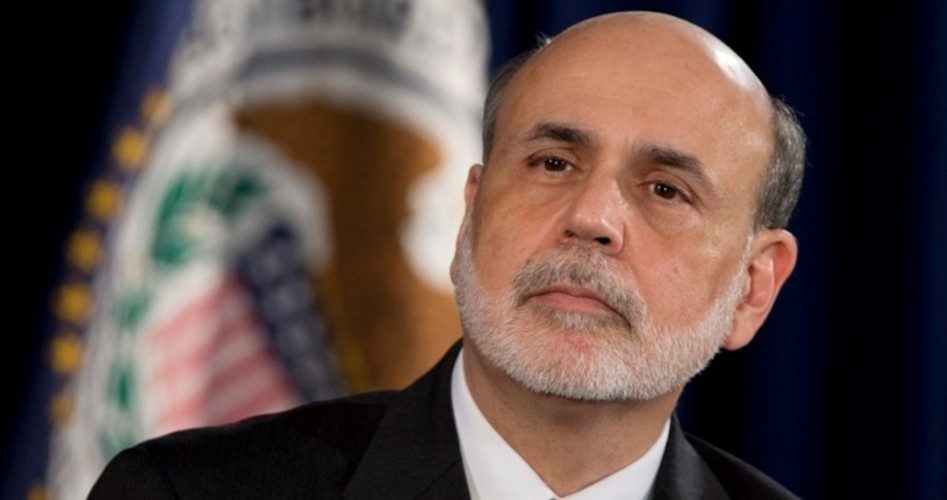

Photo of Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke: AP Images