In Les Misérables, an obsessed French police officer, Javert, relentlessly pursues Jean Valjean, a man who represents no danger to society but whose minor infraction brought down the wrath of the brutal government, including 19 years of hard labor and a lifetime of parole.

America, too, has its Javerts. Zealous and ruthless federal prosecutors have the power to torment people for trivial or imagined offenses, threatening them with decades of barbaric confinement. The consequences can be tragic even when the case is not seen through to completion. Take the example of Aaron Swartz.

Swartz faced 13 counts under the 1984 Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) and, if convicted, could have faced 35 years in federal prison and a million-dollar fine. Earlier this month the U.S. attorney in Massachusetts, Carmen Ortiz, and assistants Stephen P. Heymann and Scott L. Garland refused a plea bargain with no jail time.

On January 11 Swartz hanged himself. He was 26.

“He was killed by the government,” the Chicago Sun-Times quoted Robert Swartz, father of Aaron, as saying after the funeral. (Aaron publicly spoke of being depressed.) A family statement added, “The U.S. Attorney’s office pursued an exceptionally harsh array of charges, carrying potentially over 30 years in prison, to punish an alleged crime that had no victims.”

What did this young man do to prompt this relentless pursuit? Using the MIT computer network, he downloaded too many published scholarly articles (over four million) from JSTOR, a nonprofit database of academic journals, which charges nonacademics for access. Among his methods, Swartz planted a laptop in a closet at MIT without permission.

For this he was threatened with decades of imprisonment and the life-long stigma of being a felon. Perpetrators of financially significant crimes with victims are not treated so harshly. Why did this happen?

“He was being made into a highly visible lesson,” civil-liberties attorney Harvey Silverglate told Declan McCullagh of CNET.com. “He was enhancing the careers of a group of career prosecutors and a very ambitious — politically-ambitious — U.S. attorney who loves to have her name in lights.”

Even though Swartz was charged under an anti-hacking statute, he was not accused of hacking anyone’s computer. With unauthorized software, he simply used his own computer to download more published articles than allowed. According to Wired’s David Kravets, “The government … has interpreted the anti-hacking provisions to include activities such as violating a website’s terms of service or a company’s computer usage policy…. The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, in limiting reach of the CFAA, said that violations of employee contract agreements and websites’ terms of service were better left to civil lawsuits.”

Unfortunately, that ruling applies only in the ninth circuit. “The Obama administration has declined to appeal the ruling to the Supreme Court,” Kravets writes, where it could be affirmed and applied nationwide.

Had that happened, there might have been no case against Swartz, because JSTOR did not want to sue him, even though he crashed its servers, and he agreed not to distribute the material. (MIT had not declined to prosecute.) Subsequently, JSTOR opened its database to the nonacademic public.

So why make an example of Swartz? He was a highly public figure in the movement to safeguard the free flow of information on the Internet. Among his accomplishments was his help in defeating bills in Congress that would have given the executive branch broad authority to shut down websites accused of containing copyrighted material. The Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and the Protect Intellectual Property Act (PIPA) had the backing of powerful industries, such as Hollywood, but a grassroots effort led by Swartz and others forced withdrawal of the bills — a big setback for those who use “intellectual-property” laws to impede the sharing of information.

Swartz previously ran afoul of the government when he provided free access to records in a public federal court database. (The government requires payment by the page.) But no charges were filed.

Swartz was a passionate champion of technology’s power to liberate and democratize. He vowed to fight anything which threatened that potential. This offended powerful vested interests.

A few days after Swartz took his own life, Javert — I mean Ortiz — dropped the charges.

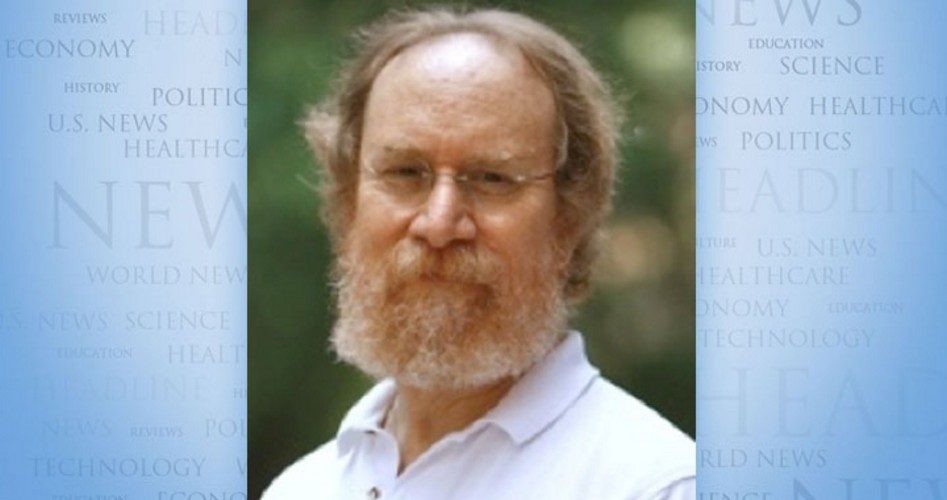

Sheldon Richman is vice president and editor at The Future of Freedom Foundation in Fairfax, Va.