Despite evidence from around the world that minimum wage laws can price low-skilled workers out of jobs, the U.S. Department of Labor is planning to extend minimum wage coverage to domestic workers, such as maids or those who drop in from time to time to do a few household chores for the sick and the elderly.

This coverage is scheduled to begin in January 2015 — that is, after the 2014 elections and nearly two years before the 2016 elections. Politicians show a lot of cleverness in protecting their own interests, even if they show very little wisdom as far as serving the public interest.

If making household workers subject to the minimum wage law is expected to produce good results, why not let those good results begin early, so that voters will know about them before the next election?

But, if this new extension of the minimum wage law opens a whole new can of worms — as is more likely — politicians who support this extension want to insulate themselves from a voter backlash. Hence artfully choosing January 2015 as the effective date, to minimize the political risks to themselves.

The reason this particular extension of the minimum wage law is likely to open a can of worms is that both household workers and those who employ them will face more complications than employers and employees in industry or commerce.

First of all, ill or elderly individuals who need someone to help them from time to time are not like employers who have a business that regularly hires people and may have a personnel department to handle all the paperwork and keep up with all the legal requirements when government bureaucrats are involved.

Often the very reason for hiring part-time household workers is that some ill or elderly individuals have limited energy or capacity for handling things that were easy to handle when they were younger or in better health. Bureaucratic paperwork and legal technicalities are the last thing they need to have to add to their existing problems.

The people being hired to do household chores also have special problems. Often such people have limited education, and may also have limited knowledge of the English language.

Why make it harder for ill or elderly people to get some much-needed help in their homes, and harder for low-skilled people to get some much-needed jobs?

Despite all the talk about how we need more people with high-tech skills, there is also a need for people who can help clean a home or carry groceries or do other things that need doing, and which do not require years of schooling. As the elderly become an ever growing proportion of the population, there will be a growing demand for such people.

More precisely, there would be more jobs for such people if the government did not step in to complicate the hiring process and price potential workers out of jobs, with minimum wages set by third parties who do not, and cannot, know what the economic realities are for either the ill and the elderly or for those whom the ill and the elderly wish to hire.

Minimum wage laws in general are usually set with no real knowledge of the economic realities and alternatives for either employers or employees. Third parties are simply enabled to indulge themselves by imagining what is “fair” — and pay no price for being wrong about the actual economic consequences.

That is why countries with minimum wage laws usually have much higher rates of unemployment than those few places where there have been no minimum wage laws, such as Switzerland or Singapore — or the United States, before the first federal minimum wage law was passed in 1931.

Government interventions in labor markets have already created needless complications, and not just by minimum wage laws. The welfare state has already taken out of the labor market millions of people who could perform work that would be well within the capacity of inexperienced young people or people with limited education.

With welfare, such people can stay home, watch television, do drugs or whatever — or else they can hang out in the streets, often confirming the old adage that the devil finds work for idle hands.

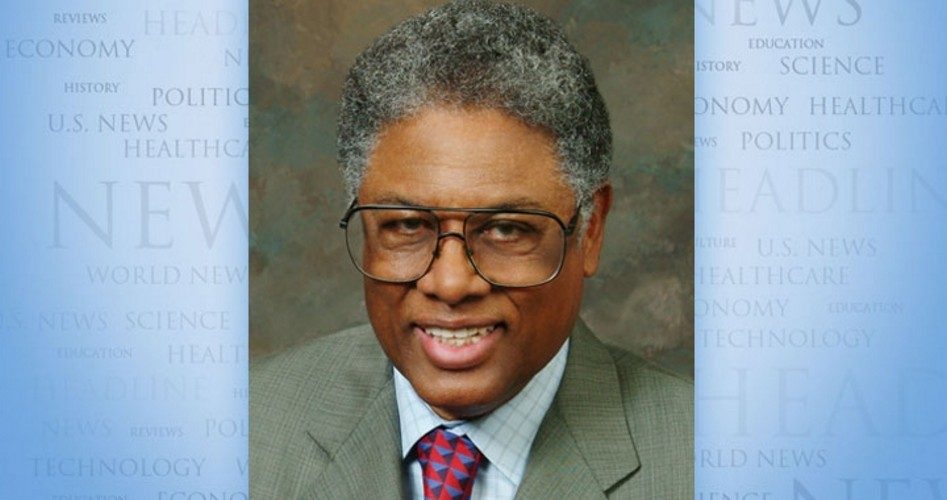

Thomas Sowell is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305. His website is www.tsowell.com. To find out more about Thomas Sowell and read features by other Creators Syndicate columnists and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate Web page at www.creators.com.

COPYRIGHT 2013 CREATORS.COM