A lot of ink has been spilled in the past several days over Sunday’s 40th anniversary of the famous break-in at the Democratic Party headquarters at the Watergate office complex in Washington, D.C. For nearly a year the major media appeared to accept then-Attorney General and future prison inmate John Mitchell’s description of the event as a “third-rate burglary” by some pro-Nixon knight-errants in a vain effort to get some “dirt” on the opposition. Little more was heard of the break-in for the rest of 1972, and it surely did no harm to Nixon’s political fortunes as the President that November carried 49 states, 10 years to the day after losing an election for Governor in California and his announcement to reporters that they would not “have Nixon to kick around anymore.” It was the completion of one of the greatest comebacks in American political history.

By the middle of the following year, however, the scandal known simply as “Watergate” was the subject of daily televised hearings of a special Senate committee, and opinion polls showed Nixon at that point would lose in a rematch with Sen. George McGovern of South Dakota, the same Democrat he buried in an avalanche of Nixon votes only months earlier. On August 9,1974, Nixon resigned rather than face an almost certain impeachment over his part in the coverup of the skullduggery, involving efforts to thwart investigations that amounted to obstruction of justice. While AG Mitchell and other officials went to prison, President Gerald Ford, who succeeded Nixon, issued a blanket pardon of any criminal activities that may have been committed by the former President and the nation’s most prominent “unindicted co-conspirator.”

The accumulation of wrongdoings lumped together under the heading “Watergate” triggered a setback for the Grand Old Party that had come to dominate presidential politics, as had been forecast by Kevin Phillips in his 1969 bestseller, The Emerging Republican Majority. Though Nixon offered little in the way of coattails for Republican congressional candidates in either his squeaker of a victory in 1968 or his landslide reelection of 1972, his victories did inaugurate a Republican era in which GOP candidates won the White House in five out of six consecutive elections. Jimmy Carter was the lone exception, narrowly defeating Ford in 1976, when Watergate and Ford’s pardon of Nixon still overshadowed national politics. Republicans were placed on the defensive, reduced to a “So’s your old man” argument, with frequent references to leading Democrat Sen. Edward M. Kennedy’s midnight ride at Chappaquiddick that resulted in the death of the young, unmarried woman who was his lone passenger. “Nobody drowned in Watergate,” was oft-heard comparison between the two scandals. A more substantial attempt to show Nixon’s transgressions had the power of precedent behind them was made by journalist Victor Lasky, whose compilation of similar offenses by Franklin D. Roosevelt and later Presidents was published under the title It Didn’t Start With Watergate.

But then neither did Nixon’s crimes. Robert Parry, in a well-documented article on Consortium.com, reviewed the abundant evidence that Nixon and his allies in 1968 intervened with the government of South Vietnam to undermine negotiations they feared might lead to an outbreak of peace in Vietnam on the eve of the November election. J. Edgar Hoover was aware of it, and President Lyndon Johnson complained to Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen (R-Ill.) that the interference by the Nixon campaign bordered on treason. After the peace talks fell apart when the Saigon government refused to participate, Nixon won election over Vice President Hubert Humphrey by roughly half a percentage point. Once in office Nixon was eager to put his hands on documentary evidence of his efforts to sabotage the peace talks and did not find them in the White House. Believing they might be in the Brookings Institution, Nixon’s plumbers broke in there in an attempt to lay hold of the documents. They didn’t find them, as Johnson apparently took them with him to the ranch and the secret with him to the big ranch in the sky when he died on January 22, 1973.

But Johnson, while sinned against, was hardly sinless. He inherited from his assassinated predecessor something of a commitment to help South Vietnam defend itself from the communist Viet Cong and North Vietnam’s effort to conquer the South. And Johnson, with his talk of nailing “the coonskin to the wall,” did not want to be the President who lost the war in Vietnam. So he kept looking for opportunities to escalate the war and bring America’s tremendous air, sea, and land forces to bear on the effort to defeat the guerrilla war being waged against the government in Saigon. Throughout the spring of 1964, targets for aerial bombardment were being chosen and plans laid for a “retaliatory response” if only communist North Vietnam would cooperate by providing a pretext.

The break came on August 2 and 4, 1964. American patrol boats were accompanying South Vietnamese boats making attacks on the coast of North Vietnam. The U.S. ship the Maddox exchanged fire with North Vietnamese vessels on August 2. But it was an alleged second attack on August 4 that provoked the response that made history. This is from an internal report of the “incident” by the National Security Agency, finally declassified in 2005, 41 years after the event. Concerning the encounter of August 2, the report said:

At 1500G, Captain Herrick (commander of the Maddox) ordered Ogier’s gun crews to open fire if the boats approached within ten thousand yards. At about 1505G, the Maddox fired three rounds to warn off the communist boats. This initial action was never reported by the Johnson administration, which insisted that the Vietnamese boats fired first.

Concerning August 4, the report said emphatically: “It is not simply that there is a different story as to what happened; it is that no attack happened that night…. In truth, Hanoi’s navy was engaged in nothing that night but the salvage of two of the boats damaged on August 2.”

Yet President Johnson went on the air shortly before the 11 o’clock news to announce that the Maddox and a companion ship, Turner Joy were fired upon by the North Vietnamese and that he had, as a result, ordered a retaliatory air strike on North Vietnam. Within a few days, the Vietnam Resolution, more often referred to as the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, was passed overwhelmingly in both houses of Congress. It authorized the President to take whatever military measures would be necessary to defend South Vietnam and protect the lives of American servicemen stationed there. The resolution would be used as the legal basis for successive escalations of the war until the U.S. troop level in South Vietnam reached 500,000 and daily and nightly air attacks pulverized targets in North Vietnam as well as Viet Cong sanctuaries in the South. In Nixon’s first term, U.S. troops invaded Cambodia to rout communists forces from sanctuaries in that country, prompting widespread protests, including a riotous one at Kent State that resulted in the death of four students and the wounding of more than a dozen others.

When challenged on the constitutionality of waging an undeclared war, Johnson administration officials called the Vietnam Resolution the “functional equivalent of a declaration of war.” Thus, did the administration gain maximum leverage out of an attack on U.S. ships that, in fact, did not occur. The confusion on the evening of August 4 may have resulted from an initial report of radar images that were mistaken for torpedoes, giving rise to the legend of “Tonkin ghosts.” Indeed, a tape of telephone conversations between President Johnson and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara indicates neither man was sure of what happened in the Tonkin Gulf on the night in question. What they agreed on, however, was the timing of a “retaliatory” strike. The planes would be making their attack and Johnson would be making his announcement to the nation in time to be on the 11 o’clock news in the Eastern time zone.

Virtually everyone supported the President’s action, including Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona, Johnson’s Republican opponent. Only two members of the Senate voted against the Vietnam Resolution: Wayne Morse of Oregon and Ernest Gruening of Alaska. In Senate hearings held in 1967, Morse charged that the United States was the provocateur in the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incidents. His was a decidedly minority and, in the eyes of some, unpatriotic position. But history has borne him out.

So if Johnson’s effort to end the war was sabotaged by Nixon just a few days before a successful breakthrough on the peace front might have helped Johnson’s Vice President win the election, perhaps Johnson reaped, and Humphrey suffered, what the old wheeler-dealer had sown when he conjured up a pretext for war in 1964.

The term “Watergate” has always been used to describe far more than the mere break-in at the complex of that name on the night of June 17, 1972. It refers mainly to the coverup and obstruction of justice by the Nixon administration and the President himself, as well as any number of “dirty tricks” played on the Democrats or, indeed, any of the prominent antiwar activists on the President’s “enemies list.” One of the worst was carried out in 1971 when Nixon’s plumbers burglarized the office of the psychiatrist treating Daniel Ellsberg, the Department of Defense official who released the Pentagon Papers to the press. Perhaps when still more documents undergo yet more long overdue declassification, we will learn that confessionals were bugged to gain “dirt” on Catholic dissidents.

Watergate was not an isolated event. Victor Lasky was right: Illegal wiretaps and secret electronic listening devices were employed long before Nixon came to the White House. Indeed, Nixon was said to have discovered one bug under his own bed when he was looking for a misplaced shoe. And Watergate-like events have occurred since Nixon left in disgrace. The manufactured pretext for the war with Iraq in 2003 is one example. And the imprisonment, still without trial, of Bradley Manning and the anticipated prosecution of Daniel Assange over the WikiLeaks scandal appears in many ways to be the Ellsberg case déjà vu. Latin American revolutionary Che Guevera in the 1960s spoke of creating “two, three, many Vietnams.”

Western democratic political leaders have managed to create “two, three, many Watergates.”

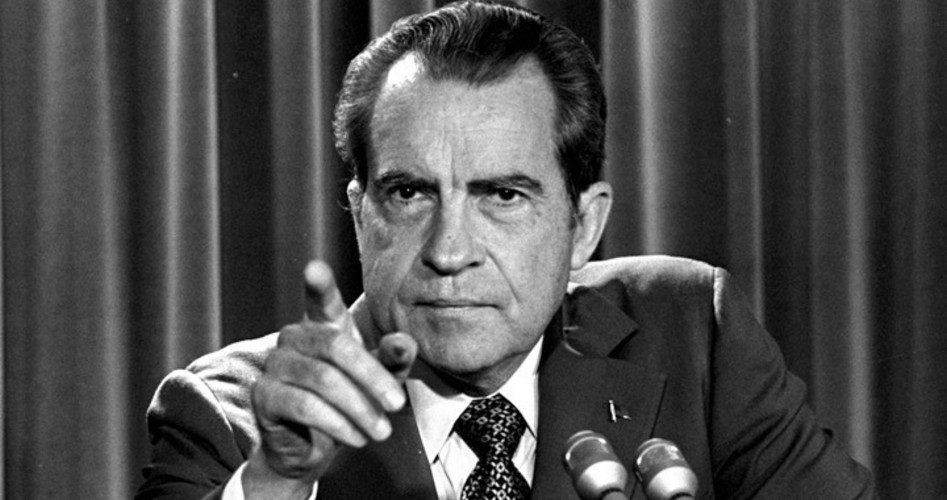

Photo of Richard Nixon: AP Images