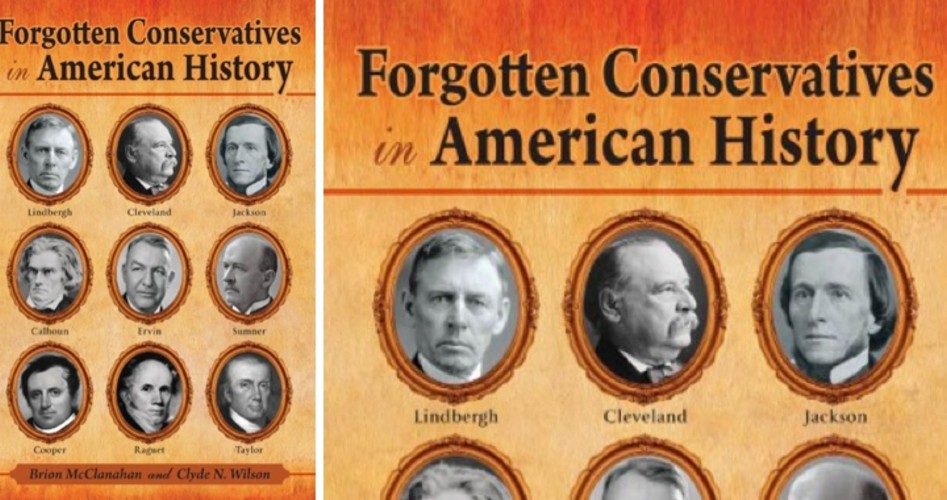

A new book, Forgotten Conservatives in American History, is dedicated to the task of ensuring such conservatives are forgotten no longer. Its authors — noted historian Clyde N. Wilson and one of his former students, Brion McClanahan — have masterfully gathered brief accounts of nearly two dozen men who made their own significant contributions to the American Republic.

The book fills an interesting niche within the realm of the history of American Conservatism. One might describe it as a cross between an appendix to Russell Kirk’s classic The Conservative Mind and Chilton Williamson’s The Conservative Bookshelf. The authors have highlighted many of the more significant writings of the “forgotten conservatives” whom they have elected to profile; on several occasions, this reviewer found their recommendations quite helpful. Indeed, a careful study of Forgotten Conservatives could furnish a reader with ample opportunities for further study of its subjects for years to come. As with Williamson’s book, an attentive reading of this book leaves one buried under a heap of titles that one may never have encountered before, but without which one is no longer content to remain.

The connection between this book and The Conservative Mind is overt; as the authors explain in their introduction, “We have chosen to be guided by Russell Kirk’s classic The Conservative Mind in identifying who is a conservative.” Since the entire purpose of the book is to give attention to those individuals who have been neglected — even forgotten — by modern conservatives, it is necessary that the book has much the feel of a title to be read after a thorough study of Kirk’s classic work.

One aspect of the great service that McClanahan and Wilson have provided to their readers is their clear understanding of what constitutes true conservatism; they have little use for the self-important neoconservatives and the processed puffery that passes for political discourse in modern America. The authors sought out genuine conservatives, and succinctly summarize their lives and contribution to the Republic, offering readers sufficient depth of detail to whet their appetites. If one reads Forgotten Conservatives and is left wondering, first, where such men may be found today and, second, whether we are worthy of those who have contributed so much to these United States in the past, then the labors of McClanahan and Wilson have not been in vain.

The authors’ forgotten conservatives span the history of the Republic from the days immediately following the War of Independence to the present. The unifying theme throughout the chapters is the fundamentally Jeffersonian character of their heroes, and the Hamiltonian hearts of their villains. Such characterizations are hardly a surprise — Clyde Wilson’s Jeffersonian approach to the history of the Republic (e.g., From Union to Empire: Essays in the Jeffersonian Tradition [2003]) is in full force in Forgotten Conservatives. On occasion, there is a repetitive character to the invocation of the American tension between Jeffersonians and Hamiltonians; the hermeneutical key provided by that tension might have been more effective if it had not been invoked in nearly ever chapter. Sometimes the strength of such an insight is more powerful when less-frequently restated.

Another abiding impression throughout Forgotten Conservatives is that the men included in this work were profoundly opposed to the wars in which the Republic was embroiled time and again. They were patriots — in fact, several were distinguished on account of their brave service in times of war — but from the War of 1812, to the War between the States, to the Spanish-American War, to the First and Second World Wars, many of the “forgotten conservatives” were men who endangered their own public standing by opposing the popular wars of their times.

Forgotten Conservatives include among their ranks statesmen, authors, historians, economists, and philosophers. In this reviewer’s opinion, the chapters on Presidents John C. Calhoun and Grover Cleveland are two of the strongest in the entire work — not surprising, perhaps, given the fact that Wilson is the editor of The Papers of John C. Calhoun. The chapters concerning James Fenimore Cooper, James Gould Cozzens, and William Faulkner also offer readers an opportunity to reflect on several of the fine conservative minds who have actively contributed to the literary heritage of these United States.

Still, some of the authors’ selections are odd, to say the least. Consider, for example, “H.L. Mencken as Conservative” — the tentative character of the chapter’s title seems an admission by the authors that the claim that is upholding its central contention is tenuous, at best. Mencken’s cultivated misanthropy and his reviling of traditional American religious belief may seem amusing, on occasion, but the fact that he turned his blade against politicians of the Left is insufficient to redeem Mencken in any sense which comports with Kirk’s definition in The Conservative Mind — which the authors recognize as the standard by which they are operating.

Nevertheless, Forgotten Conservatives is a book worthy of careful study. McClanahan and Wilson have provided a powerful testimony to the enduring strength of conservative principles through the history of these United States.

Forgotten Conservatives in American History, by Brion McClanahan and Clyde N. Wilson, Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing Co., 2012, 199 pages, hardcover.