People in the media and academia are mostly leftists hellbent on growing government and controlling our lives. Black people, their politicians and civil rights organizations have become unwitting accomplices. The leftist pretense of concern for the well-being of black people confers upon them an aura of moral superiority and, as such, gives more credibility to their calls for increasing government control over our lives.

Ordinary black people have been sold on the importance of electing blacks to high public office. After centuries of black people having been barred from high elected office, no decent American can have anything against their wider participation in our political system. For several decades, blacks have held significant political power, in the form of being mayors and dominant forces on city councils in major cities such as Philadelphia, Detroit, Washington, Memphis, Tenn., Atlanta, Baltimore, New Orleans, Oakland, Calif., Newark, N.J., and Cincinnati. In these cities, blacks have held administrative offices such as school superintendent, school principal and chief of police. Plus, there’s the precedent-setting fact of there being 44 black members of Congress and a black president.

What has this political power meant for the significant socio-economic problems faced by a large segment of the black community? Clearly, it has done little or nothing for academic achievement; the number of black students scoring proficient is far below the national average. It is a disgrace — and ought to be a source of shame — to know that the average white seventh- or eighth-grader can run circles around the average black 12th-grader in most academic subjects. The political and education establishment tells us that the solution lies in higher budgets, but the fact of business is that some of the worst public school districts have the highest spending per student. Washington, D.C., for example, spends more than $29,000 per student and scores at nearly the bottom in academic achievement.

Each year, roughly 7,000 — and as high as 9,000 — blacks are murdered. Ninety-four percent of the time, the murderer is another black person. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, between 1976 and 2011, there were 279,384 black murder victims. Contrast this with the fact that black fatalities during the Korean War (3,075), Vietnam War (7,243) and wars since 1980 (about 8,200) total about 18,500. Young black males have a greater chance of reaching maturity on the battlefields than on the streets of Philadelphia, Chicago, Detroit, Oakland, Newark and other cities. Black political power and massive city budgets have done absolutely nothing to ameliorate this problem of black insecurity.

Most of the problems faced by the black community have their roots in a black culture that differs significantly from the black culture of yesteryear. Today only 35 percent of black children are raised in two-parent households, but as far back as 1880, in Philadelphia, 75 percent of black children were raised in two-parent households — and it was as high as 85 percent in other places. Even during slavery, in which marriage was forbidden, most black children were raised with two biological parents. The black family managed to survive several centuries of slavery and generations of the harshest racism and Jim Crow, to ultimately become destroyed by the welfare state. The black family has fallen victim to the vision fostered by some intellectuals that, in the words of a sociology professor in the 1960s, “it has yet to be shown that the absence of a father was directly responsible for any of the supposed deficiencies of broken homes.” The real issue to these intellectuals “is not the lack of male presence but the lack of male income.” That suggests that fathers can be replaced by a welfare check. The weakened black family gives rise to problems such has high crime, predation and other forms of anti-social behavior.

The cultural problems that affect many black people are challenging and not pleasant to talk about, but incorrectly attributing those problems to racism and racial discrimination, a need for more political power, and a need for greater public spending condemns millions of blacks to the degradation and despair of the welfare state.

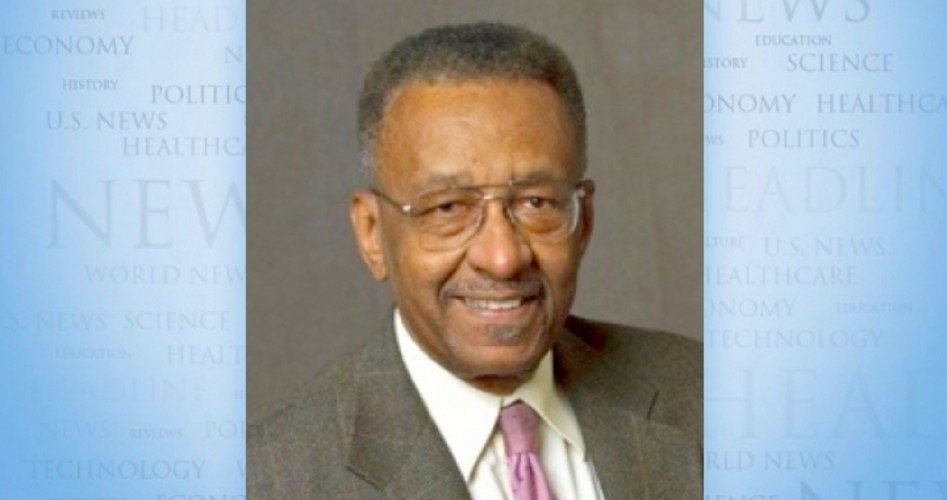

Walter E. Williams is a professor of economics at George Mason University. To find out more about Walter E. Williams and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate Web page at www.creators.com.

COPYRIGHT 2014 CREATORS.COM