“Whether one is a conservative or a radical, a protectionist or a free trader, a cosmopolitan or a nationalist, a churchman or a heathen, it is useful to know the causes and consequences of economic phenomena.” That quotation, from Nobel laureate George J. Stigler, is how Dr. Thomas Sowell begins the fifth edition of Basic Economics. It’s a book that explains complex economic phenomena in a way that many economists cannot. And, I might add, it provides an understanding of some economic phenomena that might prove elusive to a Ph.D. economist.

Basic Economics is a 653-page book, not including the index. One doesn’t have to start reading it at the beginning. Near the book’s end, there’s a section titled “Questions,” and it points the reader to answers. How about this question: How can the prices of baseball bats be affected by the demand for paper or the prices of catcher’s mitts be affected by the demand for cheese? Another question easily answered is: Why would luxury hotels be charging lower rates than economy hotels in the same city? Then there’s: Can government-imposed prices for medical care reduce the cost of that care? I’m not going to give the answers away; you’ll have to read the book. The bottom line is that an understanding of material contained in Basic Economics would prevent us from falling easy prey to charlatans, hustlers and quacks.

Sowell points out that the most basic thing that can be said about economics is that we live in a world of scarcity. That means — whether our policies, practices and institutions are wise or unwise, noble or ignoble — there is never enough of anything to satisfy all of our desires. What are sometimes called “unmet needs” are inherent to any society, whether it’s capitalist, socialist, feudal or any other kind of society.

Economics is not just about goods and services that we enjoy as consumers. It’s more fundamentally about productivity — that is, how the use of land, labor, capital and other inputs that go into producing the volume of output determines a nation’s wealth. Decisions about how to use those inputs may be more important than the resources themselves. There are countries, such as Japan and Switzerland, that have far greater wealth than countries — for example, Uruguay and Venezuela — that are far richer in natural resources.

I would add as an aside to Sowell’s discussion that the human mind is the ultimate resource. I’ve asked students why it was that George Washington didn’t have guided missiles with which to pummel the British or a cellphone to communicate with his troops. After all, the physical resources that are necessary to make missiles and cellphones were around at the time. In fact, the physical resources were also around at the time of the caveman. What wasn’t around was the ingenuity from the human mind to make missiles and cellphones.

One part of Sowell’s introductory chapter deals with the role of economics. A popular misconception is that economics is about opinions, running a business or the ups and downs of stock markets. Economics is a systematic study of cause and effect, showing what happens when you do specific things in specific ways. The path to understanding outcomes is to examine consequences of decisions in terms of incentives they create rather than goals they pursue.

Paying attention to goals rather than incentives has been responsible for disastrous public policy. The minimum wage law is one example. Its goal is to provide “living wages.” It creates incentives for employers to reduce and seek substitutes for labor and thereby causes unemployment for some workers. Rent control laws are enacted to provide “affordable housing.” They provide incentives for landlords to convert apartments to condominiums, create black markets and reduce housing construction in rent-controlled areas.

The fact that Sowell’s Basic Economics has been translated into seven different languages speaks well of its usefulness in transmitting fundamental economic understanding. Reading it can benefit ordinary people, as well as Ph.D. economists.

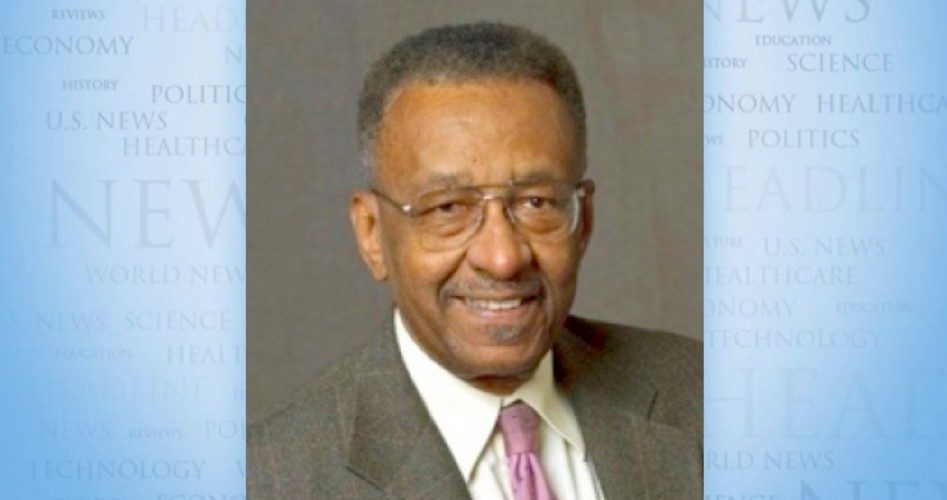

Walter E. Williams is a professor of economics at George Mason University. To find out more about Walter E. Williams and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate Web page at www.creators.com.

COPYRIGHT 2015 CREATORS.COM