And for support of this Declaration, with a firm Reliance on the Protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our Sacred Honor. — Declaration of Independence

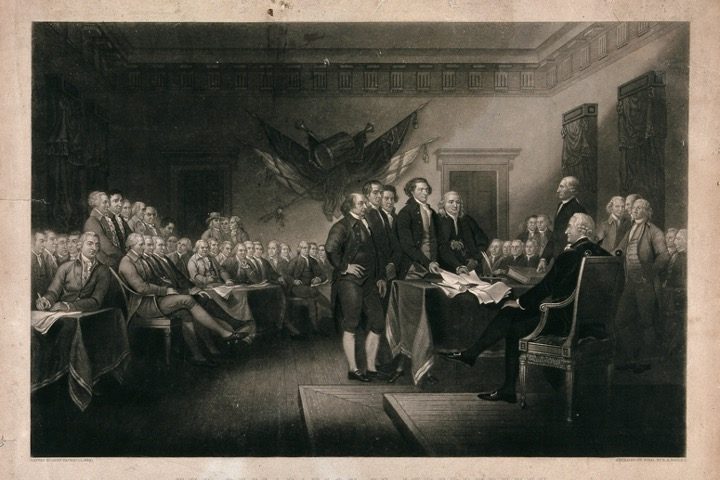

Months before they met to consider Richard Henry Lee’s motion for independence from Great Britain, the representatives of the several states serving in the Second Continental Congress knew that the simple act of sitting in that room in the State House in Philadelphia constituted an act of treason. On August 23 of the previous year, King George III had issued the “Proclamation, For suppressing Rebellion and Sedition” declaring:

[T]hat all Our Subjects of this Realm and the Dominions thereunto belonging are bound by Law to be aiding and assisting in the Suppression of such Rebellion, and to disclose and make known all traitorous Conspiracies and Attempts against Us, Our Crown and Dignity ; And We do accordingly strictly charge and command all Our Officers as well Civil as Military, and all other Our obedient and loyal Subjects, to use their utmost Endeavours to withstand and suppress such Rebellion, and to disclose and make known all Treasons and traitorous Conspiracies which they shall know to be against Us, Our Crown and Dignity ; and for that Purpose, that they transmit to One of Our Principal Secretaries of State, or other proper Officer, due and full Information of all Persons who shall be found carrying on Correspondence with, or in any Manner or Degree aiding or abetting the Persons now in open Arms and Rebellion against Our Government within any of Our Colonies and Plantations in North America, in order to bring the condign Punishment [upon] the Authors, Perpetrators and Abettors of such traitorous Designs.

Simply by meeting together — and particularly by signing the Declaration of Independence — those 56 men understood they were violating that royal proclamation and that they were now branded as traitors to the realm. Furthermore, they were well aware of the punishment to be imposed on them should they be apprehended by the officers — civil or military — of the king:

You are to be drawn on hurdles to the place of execution, where you are to be hanged by the neck, but not until you are dead; for, while you are still living your bodies are to be taken down, your bowels torn out and burned before your faces, your heads then cut off, and your bodies divided each into four quarters, and your heads and quarters to be then at the King’s disposal; and may the Almighty God have mercy on your souls.

Having the courage to sign what amounted to a death warrant is sufficient display of dauntless courage to justify reverence for those 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence as heroes. In 1857, the anonymous author of the essay “American’s Own Book” pleaded with posterity to remember the selfless sacrifice of these men:

The memories of few men will perhaps be cherished, by their posterity, with more jealous and grateful admiration than those of the patriotic individuals, who first signed the political independence of our country. They hazarded by the deed not only their lands and possessions but their personal freedom and their lives, and when it is considered that most of them were in the vigor of existence, gifted with considerable fortune, and with all the offices and emoluments at the disposal of royalty within their reach, the sacrifice which they risked appears magnified, and their disinterested patriotism more worthy of remembrance.

So that their memories might be cherished, we thought it appropriate and timely to provide a very brief overview of a handful of those 56 men whose lives, fortunes, and sacred honor were most severely affected by their patriotism and their unwavering dedication to the inestimable gift of freedom granted to all mankind by a gracious God.

And while neither the list nor the biographies is of a length worthy of their sacrifice, each of these men deserves a bit of your time and all of your thanks as you celebrate the independence that they declared in defiance of a king and heedless of his tyrannical proclamation and its promise of execution.

Thomas Nelson Jr. (Virginia): Suffered financial ruin after pledging his fortune to support the war effort. His home was occupied by British forces, and he personally helped finance the Virginia militia and Continental Army, accumulating significant debts. Nelson’s generosity was never more exemplified than when, as commander of the Virginia militia, he gave money and support to over 100 families of men whose service in the Virginia militia left them in danger of losing their farms. Finally, seeing that British officers had occupied his own home and were eating his food and drinking his wine, he ordered his men to open fire, placing even his own home on the altar of freedom.

Richard Stockton (New Jersey): A lawyer and landowner, Stockton endured immense hardship during the Revolutionary War. As a signer of the Declaration, Stockton became a target of British loyalists. He was captured in 1776, enduring brutal treatment during his imprisonment. His health suffered, and his financial situation deteriorated. Although released in 1777, he faced the loss of his estate and possessions. Despite these setbacks, Stockton demonstrated resilience and continued to serve his country in various capacities after the war.

Thomas Heyward Jr. (South Carolina): A planter and lawyer, Heyward experienced the devastating impact of British occupation and imprisonment. After signing the Declaration, he fell victim to the British invasion of Charleston in 1780. Heyward was captured, enduring the horrors of imprisonment for an extended period. The consequences were severe, and his extensive property was confiscated, leading to financial ruin. The hardships suffered by Heyward and his family underscore the price they paid for the cause of independence.

Arthur Middleton (South Carolina): A wealthy South Carolina plantation owner, Middleton demonstrated unwavering dedication during the Revolutionary War. His vast estate, Middleton Place, was plundered and destroyed during the British invasion of Charleston. Middleton himself was captured and held captive for nearly a year. These hardships resulted in the loss of personal belongings and financial ruin. Despite the profound setbacks, Middleton’s commitment to the revolutionary ideals and his subsequent contributions to his state and nation endure as a testament to his resolute spirit.

Oliver Wolcott (Connecticut): Oliver Wolcott, a Connecticut signer, dedicated himself to the Revolutionary cause. He served in the Continental Army, rising to the rank of brigadier general. Wolcott faced personal hardships when his home was burned down by British forces in 1779. Despite the loss, he continued to serve his country in various capacities.

Francis Lewis (New York): Lewis, a wealthy merchant from New York, suffered greatly during the Revolutionary War. After he signed the Declaration, his property in Long Island was ransacked and destroyed by British forces. Lewis’ wife was captured and imprisoned, enduring harsh treatment. The strain of these hardships took a toll on Lewis’ health, leaving him in poor condition.

Philip Livingston (New York): Another New York signer, Livingston faced significant personal and financial losses during the war. His estates and properties in New York City and the Hudson Valley were occupied and damaged by British troops. Livingston’s sacrifices and contributions to the revolutionary cause left him in dire financial straits.

Thomas McKean (Delaware): McKean, a Delaware signer, faced numerous hardships during the Revolutionary War. He served in the Continental Congress and the Continental Army, often enduring dangerous situations. For his ardent and consistent denunciation of British deprivation of American rights, McKean was pursued by British loyalists and lived under constant threat of imprisonment and execution.

These few examples highlight the diverse hardships experienced by the signers of the Declaration of Independence. They faced the rigors and danger of battlefields, property confiscation, ruinous financial downfalls, irreversible personal losses, and innumerable physical distress as they dedicated themselves to the cause of American independence.

These men, and every one of the others who signed the Declaration of Independence, understood, proclaimed, and practiced the following observation penned by Thomas Paine in December 1776:

What we obtain, too cheap, we esteem too lightly:—’Tis dearness only that gives every thing its value. Heaven knows how to set a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange indeed, if so celestial an article as Freedom should not be highly rated. — (“The American Crisis” No. 1)