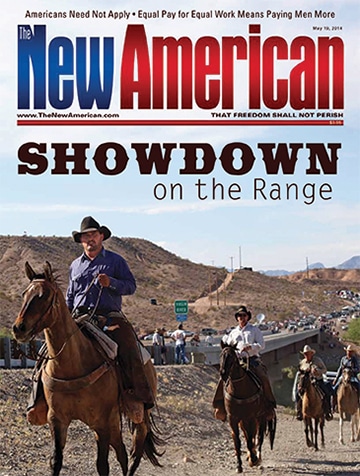

Feds vs. the West

The Nevada cattle rancher in the white cowboy hat and his supporters had massed in defiance of federal policies and agencies that threatened to drive them into extinction. To the cheers of locals, the rancher climbed aboard a Caterpillar bulldozer and plowed open a county road that had been closed by the U.S. Forest Service (USFS). Are we talking about Cliven Bundy in 2014? No, the white-hat rancher to whom we are referring was Richard “Dick” Carver, a longtime county commissioner in Nevada’s sprawling and sparsely populated Nye County, and the date was July 4, 1994 — Independence Day, 20 years ago.

Carver’s act of defiance earned him a cover on Time magazine, which showed Carver and some of his supporters, with a super-imposed headline “Don’t Tread on Me,” followed by the subtitle, “An inside look at the West’s growing rebellion.”

While the federal government claims 84.5 percent of Nevada — the highest of any state — in Nye County the federal footprint covers over 93 percent, and federal bureaucrats in Washington, D.C., dominate virtually every aspect of Nye County inhabitants’ lives. Nye County, the nation’s third largest county, was also home to the late Wayne Hage, the feisty rancher/scholar who, for decades, courageously fought the federal government in court — and won landmark decisions for property rights. Hage was also author of the 1989 book Storm Over Rangelands: Private Rights in Federal Lands, a ground-breaking work on the history of the Western states, particularly as it relates to politics, governance, land use, and property rights. It is not surprising then that Nye County became the face of what is known as the “Sagebrush Rebellion II,” an effort by citizens in Western states to wrest control away from oppressive federal bureaucrats. The efforts by Carver, Hage, and others in the late 1980s-1990s were a continuation and resurgence of earlier efforts in the 1970s-1980s, often referred to as Sagebrush Rebellion I. Carver challenged the federal road closures in court.

In 1866, Congress passed the Mining Act (Revised Statute 2477) providing the right of way for construction of roads over federal “public lands.” For a century this gave protection to county roads, many of which are literally lifelines for small towns and rural communities. But following passage of the 1964 Wilderness Act and the 1976 Federal Land Policy and Management Act, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and USFS began restricting and closing roads, even those that had been grandfathered in for protected legal status owing to their legacy under the 1866 Mining Act.

But in 1996, U.S. District Judge Lloyd D. George decided against Commissioner Carver and Nye County, ruling that the federal government “owns and has the power and authority to manage and administer the unappropriated public lands and National Forest System lands within Nye County, Nev.” Dick Carver died in 2003. Wayne Hage died in 2006. But Judge Lloyd George is still on the bench as a senior judge, and it was he who signed the permanent injunction against Cliven Bundy that initiated the recent standoff with the BLM. And, of course, the BLM, USFS, National Park Service (NPS), and the other federal agencies that dominate the Western public lands are still alive and kicking — more than ever. In fact, even though these agencies already “own” vast swaths of territory covering hundreds of millions of acres, virtually all of them have been on huge acquisition drives to acquire still more land. The map below graphically portrays the enormous fedgov footprint in the Western states.

Even a quick glance easily reveals there is a striking difference between the federal government’s claim to physical real estate in the states of the East and the Midwest versus those of the West. In Maine, for instance, federal agencies occupy only 1.1 percent of the state’s land area; in New York it’s a mere 0.8 percent. The federal government claims only 1.8 percent of Indiana, 1.6 percent of Alabama, and 1.7 percent of Ohio.

But in the Western states, the federal footprint covers from nearly one-third to over four-fifths of the area of the states. Consider and contrast the rest of the country with the federal government’s ownership in the Western states:

Nevada: 84.5 percent

Alaska: 69.1 percent

Utah: 57.4 percent

Oregon: 53.1 percent

Idaho: 50.2 percent

Arizona: 48.1 percent

California: 45.3 percent

Wyoming: 42.4 percent

New Mexico: 41.8 percent

Colorado: 36.6 percent

Washington: 30.3 percent

Montana: 29.9 percent

The Founding Fathers never intended that the federal government would permanently own and control these vast expanses of land in the new territories that would be admitted into the Union. In fact, at the time our nation was being formed, several of the original 13 eastern states (the former colonies) had laid claim to lands to the west. Those states without Western claims knew they would be disadvantaged and argued that the Western lands should be transferred to the federal government for temporary custody, until they could be “disposed” of to settlers, and, later, to what would become states, as the territories were admitted as sovereign states.

Virginia’s Act of Cession of 1784, which became a model for others, stipulated that the ceded lands would be disposed of for revenue for the United States and the creation of new member states, “and shall be faithfully and bona fide disposed of for that purpose, and for no other use or purpose whatsoever.”

Thomas Jefferson insisted that the federal government must dispose of all its vast domain, and that the land should “never after, in any case, revert to the United States.”

However, virtually from the beginning, the powerful East Coast commercial and banking interests sought to keep as much of the Western lands that they were unable to purchase bottled up, so that new dynamic centers of productivity and commerce would not emerge to compete with and challenge their dominance. Although the new states were promised that upon admission the federal government would “extinguish title,” the “Western states” of 1828 (Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, Alabama) had to force the federal government to dispose of the lands, as promised in their Admission Acts or Enabling Acts.

In a speech before Congress in 1828, Representative Joseph Duncan of Illinois reminded Congress of the duty to dispose of federally held lands. He noted:

If these lands are to be withheld, which is the effect of the present system, in vain may the People of these states expect the advantages of well settled neighborhoods, so essential to the education of youth.... Those states will, for many generations, without some change, be retarded in endeavors to increase their comfort and wealth, by means of works of internal improvements, because they have not the power, incident to all sovereign states, of taxing the soil, to pay for the benefits conferred upon its owner by roads and canals. When these States stipulated not to tax the lands of the United States until they were sold, they rested upon the implied engagement of Congress to cause them to be sold, within a reasonable time. No just equivalent has been given those states for a surrender of an attribute of sovereignty so important to their welfare, and to an equal standing with the original states.

This “equal standing” or “equal footing” principle was confirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1845 decision in Pollard v. Hagan. The court ruled against the federal government’s claims in Alabama, which had been created from territory ceded by Georgia. In the landmark Pollard decision, the court held:

The United States never held any municipal sovereignty, jurisdiction or right of soil in and for the territory, of which Alabama or any of the new states were formed, except for temporary purposes, and to execute the trusts created by the acts of the Virginia and Georgia legislatures, and the deeds of cession executed by them to the United States, and the trust created by the treaty with the French republic of the 30th of April, 1803, ceding Louisiana.

Moreover, said the court:

Alabama is, therefore, entitled to the sovereignty and jurisdiction over all the territory within her limits, subject to the common law, to the same extent that Georgia possessed it, before she ceded it to the United States. To maintain any other doctrine, is to deny that Alabama has been admitted into the union on an equal footing with the original states, the constitution, laws, and compact, to the contrary notwithstanding.

President Andrew Jackson, in 1833, described the commitment to dispose of land in agreements with the original states as “solemn compacts” where “the States claiming those lands acceded to those views and transferred their claims to the United States upon certain specific conditions, and on those conditions the grants were accepted.” Further, he stated:

The Constitution of the United States did not delegate to Congress the power to abrogate these compacts. On the contrary, by declaring that nothing in it “shall be so construed as to prejudice any claims of the United States or of any particular State,” it virtually provides that these compacts and the rights they secure shall remain untouched by the legislative power, which shall only make all “needful rules and regulations” for carrying them into effect. All beyond this would seem to be an assumption of undelegated power.

Much more recently, a unanimous U.S. Supreme Court decision in Hawaii v. Office of Hawaiian Affairs (2009) confirmed the importance of federal commitments made at the time of entry into the Union and the inability of Congress to renege on those commitments, stating:

The consequences of admission are instantaneous, and it ignores the uniquely sovereign character of that event … to suggest that subsequent events somehow can diminish what has already been bestowed. And that proposition applies a fortiori where virtually all of the State’s public lands … are at stake.

Now, after more than a century of delay, many of the Western states are demanding their “equal footing” as sovereign states, free from the shackles of an oppressive federal “landlord.” Which is to say, merely, that they are refusing to continue tolerating a second-class status that is not tolerated by the other supposedly co-equal states to their east.

On March 23, 2012, Utah Governor Gary R. Herbert signed House Bill 148, which demands the federal government make good on the promises made in Utah’s 1894 Enabling Act (UEA) to extinguish title to federal lands in Utah.

“We need a paradigm change when it comes to public lands management. This bill creates a mechanism to put the federal government on notice that Utah must be restored to its rightful place as a co-equal partner,” said Governor Herbert. “The federal government retaining control of two-thirds of our landmass was never in the bargain when we became a state, and it is indefensible 116 years later.”

“This is only the first step in a long process, but it is a step we must take. Federal control of our public lands puts Utah at a distinct disadvantage, specifically with regard to education funding,” Herbert continued. “State and local property taxes cannot be levied on federal lands, and royalties and severance taxes are curtailed due to federal land use restrictions. Federal control hampers our ability to adequately fund our public education system.”

The bill signed by Governor Herbert gave the federal government a deadline of December 2014 to relinquish tens of millions of acres of “public lands” to the state, excluding National Parks and Wilderness Areas, which are left under national control. That deadline date is fast approaching. However, considering the potential significance of this political move, it has received almost no media coverage, hence very few people have heard about it beyond the borders of the Beehive State. One explanation for the silence is that the powers that be in the political, financial, and chattering classes haven’t taken it seriously. However, that may be about to change, as more states are looking to follow Utah’s example.

On April 18, more than 50 political leaders from nine Western states gathered in Salt Lake City to attend the Legislative Summit on the Transfer for Public Lands.

“Those of us who live in the rural areas know how to take care of lands,” said Montana State Senator Jennifer Fielder, one of the organizers, who lives in the northwestern Montana town of Thompson Falls. “We have to start managing these lands. It’s the right thing to do for our people, for our environment, for our economy and for our freedoms,” Fielder said.

Utah State Rep. Ken Ivory, one of the summit organizers, pointed out that there is an estimated $150 trillion in mineral resources “locked up in federal lands” across the West — wealth that can be put to use to help struggling American families and make the American economy stronger, more competitive, and less dependent on foreign sources for energy and critical minerals.

Idaho Speaker of the House Scott Bedke noted that Idaho forests and rangeland managed by the state are in better health and have suffered less damage and watershed degradation from wildfire than have lands managed by federal agencies. “It’s time the states in the West come of age,” Bedke said. “We’re every bit as capable of managing the lands in our boundaries as the states east of Colorado.”

One of the absurd (and tragic) ironies of the “public lands” story is that the biggest political lobby for keeping the huge tracts under Washington, D.C.’s control is composed of urbanite “environmentalists” who have been duped into supporting the present system that is killing our national forests and destroying our wildlife, habitats, and natural wonders on a monumental scale. As we’ve reported in these pages before, many government and scientific reports have noted that tens of millions of acres of national forest are dying and burning up due to neglect and mismanagement. Likewise, a report released last October by Senator Tom Coburn (R-Okla.) shows that, despite increases in funding, the National Park Service continues its decades-long trend of deferring maintenance, with the result that most of our “crown jewel” parks have fallen into serious disrepair — even as they continue to expand their holdings.

The report notes that, “despite a $256 million shortfall in maintenance funding and an $11.5 billion backlog, more than 35 bills have been introduced this year to study, create or expand national parks, monuments and heritage areas, including a bill to establish a national historic park on the moon.” Yes, a park on the moon — a fitting abode, many might think, for federal lunatics.

End Fedgov Occupation of the West

The critics who say Senator Harry Reid has never uttered a sentence that wasn’t a lie probably would exclude from that generalization the senator’s remark on April 14, “It’s not over.”

Reid was referring, of course, to the BLM-Cliven Bundy conflict, and his threatening comment implied that the next round would not end so auspiciously for the rancher. Senator Reid also must know that there are thousands more hardworking Americans like Bundy who face imminent economic ruin and loss of family farms, businesses, and homes due to the destructive policies that he and his ruling class collaborators are fastening upon our nation. This is especially true across the West, where the federal landlord’s lash falls hardest and has the longest reach. One thing is certain: The arrogant and oppressive federal agencies will drive many rural people to desperation, making more Bundy-BLM confrontations inevitable.

Perhaps Reid and his Beltway cohorts are prepared to label as “domestic terrorists” all those who oppose their steady usurpations. Perhaps they even want to provoke violent opposition as justification for ever more concentration of federal power to deal with the chaos and “civil unrest.”

But there is no need to continue on the same flawed course that will guarantee continued, and escalating, conflicts. The Western states can take the path that has been trod previously by other states. Now is the time, and the way is prepared for a peaceable, sensible, moral, and just solution to the long-standing inequity of federal dominance that has troubled the West for over a century.

Do the Western states not have same right as all the other states of these United States to determine their own destinies and manage their own affairs, free of the shackles imposed by federal bureaucrats and outside politicians? Is it not time to evict the federal bureaucrats from their Western empire and transfer the land, as originally intended, to the states and the people?