The ironies of the so-called anti-racism protests across the country are legion. Black-owned businesses have been destroyed. Black people have been killed. And now a monument to a 19th-century abolitionist has been defaced.

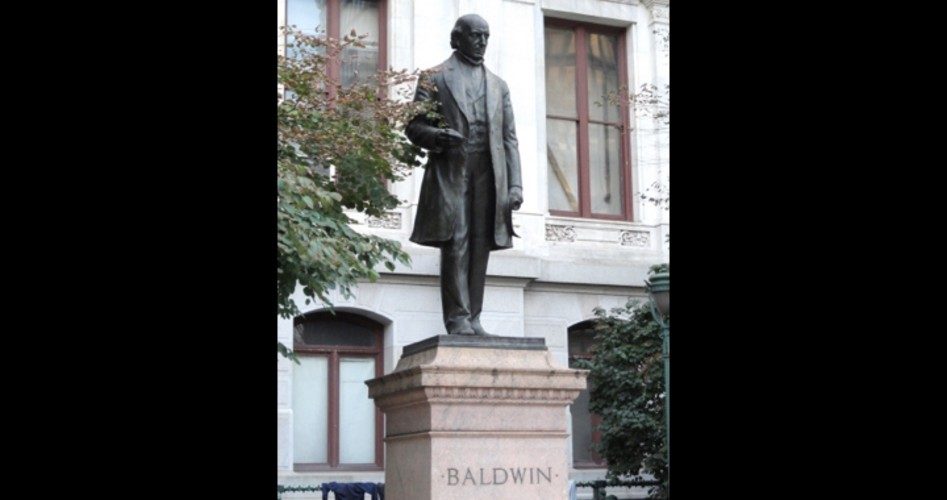

The statue of Matthias William Baldwin (shown) that has stood in front of Philadelphia’s City Hall since 1936, 30 years after its creation, was tagged with the words colonizer and murderer in the early days of the protests — probably Memorial Day weekend.

“We can confirm that the statue of Matthias Baldwin, along with other statues in the area of Philadelphia’s City Hall, was tagged with paint and graffiti at some point during the first days of protests that took place in Philadelphia,” a spokesperson for Mayor Jim Kenney’s office told the Philadelphia Inquirer late last week. “There has been no subsequent vandalism of the Baldwin statue in recent days.”

The spokesperson felt the need to mention the lack of subsequent vandalism because photos of the defaced statue went viral last week, leaving the impression that the graffiti had only recently been applied. In fact, the person said, it was cleaned off the statue immediately upon its discovery.

Why was Baldwin’s statue defaced? Apparently, simply being white and wearing colonial-era garb were sufficient reason. Had the vandal bothered to whip out his smartphone (or one he’d looted from a vandalized business) and look up Baldwin, he would have discovered he was attacking a man who did everything he could to help blacks, including supporting the abolition of slavery, often at great personal cost.

Born in 1795 in Elizabethtown, New Jersey, Baldwin moved to Philadelphia at age 16 after his father’s considerable estate was mismanaged, leaving his widow and children in dire straits. Working for others, the young man became a skilled jeweler. Then he struck out on his own, making a success of himself as a silversmith and manufacturer of printing equipment. In 1828, he built his first steam engine to help power his company. Four years later, he was in the locomotive business; the Baldwin Locomotive Works would build more than 70,000 steam locomotives over the next 125 years.

Baldwin could have been content with his business success, but he became a Christian in early adulthood and remained faithful to his Creator the rest of his life. In 1867’s Memorial of Matthias W. Baldwin, the Reverend Wolcott Calkins observed:

Mr. Baldwin’s conversion was a marked and thorough change of character. He was a whole-souled Christian from the first, and blended the spirit of childlike trust in God … with an immediate adjustment of his business to the Gospel standard of integrity, and the most aggressive labors in the cause of Christ…. His courage to defend righteous principles far in advance of his age, and illustrate them yet more conspicuously by his example, and his disposition to consecrate his wealth and influence to the good of others and the glory of God, were the fruits of this blessed experience of pure and undefiled religion.

Baldwin particularly demonstrated his faith with respect to black people, who were poorly treated even in northern states at the time. In 1835, he helped found a school for black children in Philadelphia and paid the teachers’ salaries out of his own pocket for many years. In 1837, at the Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention, he argued that blacks should have the right to vote. He also became an outspoken opponent of slavery decades before abolitionism was cool, a decision that cost him business in the South.

“He hired blacks in his shops when that was not the norm,” Joe Walsh, a member of the Friends of Matthias Baldwin Park, told National Review. “He was BLM [Black Lives Matter] before there was a slogan.”

Defacing Baldwin’s statue, then, was an act of historical ignorance. However, it may have its bright side. Jim Fennell, president of the Friends of Matthias Baldwin Park, told the Inquirer the attention the statue has received has caused people to investigate Baldwin and discover what a great man he was.

“It seems like people are suddenly looking at him and finding out he was an abolitionist and did all sorts of things to support African Americans, including integrating his work force,” he said.

Michael Tennant is a freelance writer and regular contributor to The New American.