National Geographic Channel’s movie Killing Kennedy (based on the book Killing Kennedy: The End of Camelot by Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard) premiered on November 10. It reran on November 15 and will air again on December 30.

The docudrama presents a dual timeline — one depicting the presidency of John Kennedy and a parallel dramatization about the life of Lee Harvey Oswald, who, the Warren Commission concluded, killed the president. It stars Rob Lowe as President John F. Kennedy, Will Rothhaar as Lee Harvey Oswald, Michelle Trachtenberg as Marina Oswald, and Ginnifer Goodwin as Jacqueline Kennedy.

The movie credibly presents Oswald’s pro-Soviet, pro-communist background. We first encounter him at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow (an incident that took place on October 31, 1959), where he told embassy officer Richard Snyder that he wanted to renounced his U.S. citizenship and remain in the Soviet Union.

The movie follows Oswald to Minsk, where — after being granted permission to work in the Soviet Union — authorities had assigned him to work at the Gorizont Electronics Factory. It was in Minsk where Oswald met his future Russian wife, Marina, at a trade union dance.

Oswald’s disenchantment with life in Minsk is presented more as his dislike of the severe winters than with the Soviet system per se, and after the United States generously agreed to allow his return to America, he was unappreciative and continued to harbor pro-Soviet, pro-Cuban, and pro-Marxist sentiments.

There is little reason to dispute the movie’s depiction of the FBI’s interest in Oswald’s time spent in the Soviet Union, as well as his status upon returning home in 1962. The FBI’s questions (e.g., Why did you go to Russia? Are you now or have your ever been a Communist?) are just the type of questions that diligent FBI agents should have asked.

During the Kennedy segments of the docudrama, much attention is paid to the administration’s policy towards Cuba, including the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion and the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. The rationale for devoting much attention to these two events, apparently, is to portray Kennedy as strongly anti-Castro, and since Oswald was a great admirer of Cuban dictator Fidel Castro, they fueled his resentment against President Kennedy.

This explanation is actually quite reasonable, given that Oswald was not nearly so politically sophisticated as he supposed himself to be, and in all likelihood believed whatever spin the mass media presented concerning these two events. He might well have believed that Kennedy was being “tough on Communism” and, consequently, as a Communist sympathizer, decided that Kennedy had to go.

Another public figure who aroused the ire of Oswald was Major General Edwin A. Walker, a 30-year, heavily decorated Army veteran who was an outspoken anti-communist and defender of states’ rights. Walker had utilized anti-communist John Birch Society material in his Pro-Blue (meaning, “anti-Red”) educational program for the troops under his command in Germany.

Though not mentioned in the movie, Walker very likely came to Oswald’s attention after a front page story about the general appeared in the October 7, 1962, issue of the Communist Worker newspaper to which Oswald subscribed warned “the Kennedy administration and the American people of the need for action against [Walker] and his allies.”

A scene in Killing Kennedy portrays Oswald asking a Russian friend about Walker at a backyard barbecue:

Oswald: “Joe, you’ve heard of this General, Edwin Walker?”

Russian (Joe): “Of course. He’s the crazy racist John Bircher who caused all that trouble at Old Miss.”

Oswald: “Now he wants the United States to invade Cuba. And he’s going all over the country attacking Communism….”

Russian: “And Castro. You know, Walker lives right here in Dallas.”

Oswald: “No he doesn’t.”

Russian: “Yes, he does.”

Oswald: “Really? [pause] What if someone killed Hitler before he came to power? I ask you, how many lives could have been saved?”

Russian: “Anybody who does that b*****d off will be doing the world a favor.”

Oswald then fantasizes how he would answer reporters asking him about why he killed General Walker.

Oswald’s wife, Marina, would say later that he chose Wednesday evening, April 10, 1963, to shoot Walker because the neighborhood would be crowded with worshipers attending services in a church adjacent to Walker’s home, and he could mingle with the crowds if necessary to make his escape. Walker was sitting at a desk in his dining room when Oswald fired at him from less than a hundred feet away. However, the bullet struck the wooden frame and broke apart. Walker was injured in the forearm by bullet fragments. The Warren Commission report later concluded that in March 1963, Oswald used the alias “A. Hidell” to purchase a Carcano 6.5 mm rifle by mail from Klein’s Sporting Goods in Chicago and that Oswald used that weapon to shoot at Walker in April and kill the president in November.

As for the Russian’s implication that The John Birch Society is racist (“crazy racist John Bircher”), the Russian, if he actually existed, was echoing the propaganda line of the Communist Party, which has long viewed The John Birch Society as an enemy and has maligned it as “racist,” “fascist,” etc.

But how about Walker? The way the media portrayed his participation in protests against the use of federal troops to enforce integration at the University of Mississippi — a clear violation of the Tenth Amendment — undoubtedly led many to the conclusion that he was a racist. Walker filed several libel lawsuits against media outlets whose reporting distorted his participation, and in 1964 a Texas trial court found the newspaper statements false and defamatory and awarded Walker over $3 million.

While Killing Kennedy’s compilation of the historic events related to the Kennedy assassination was generally credible, the references to the two Cuban crises followed the establishment media’s line (i.e., that the U.S. government had strongly opposed Fidel Castro’s rise to power and continued to oppose him once he consolidated power) and, therefore, missed the mark.

While refuting the many instances of misreporting that prevented most Americans from learning the whole truth about Castro’s rise to power, the Bay of Pigs invasion, and the Cuban Missile Crisis would take several articles, consider just the following examples of how the reported stories departed from the truth:

An important point generally overlooked is the U.S. government’s denial of Castro’s Communist background and not-so-passive acquiescence to his seizure of power. Michael E. Telzrow noted in his article for The New American: “In close cooperation with New York Times reporter Herbert Matthews, the State Department kept up Castro’s noncommunist appearance. It was a deception that worked amazingly well in the halls of Congress and on the American street.”

Among the actions that the U.S. government took to aid Castro’s revolution, notes Telzrow: “In March 1958, U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles dealt a death blow to the [pre-Castro] Batista government by refusing to ship 1,950 Garand rifles legally purchased by the Cuban government. It was a mortal blow from which Batista failed to recover. Dulles claimed that he took this action in the interest of ‘nonintervention,’ but here again the United States was essentially providing aid to Castro’s forces by subverting the efforts of the national government.”

Killing Kennedy depicted the president as being taken completely off-guard at the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion, but nobly willing to accept responsibility for the failure, as any commander-in-chief should.

However, in his critical analysis of the Kennedy administration, Kennedy’s 13 Greatest Mistakes In The White House, Malcolm E. Smith asserted that President Kennedy played a proactive role in suspending the air support that doomed the Bay of Pigs invasion: “The order came from the President. It did not mince words. There was to be no second air strike that morning. The B-26’s were to stand down. The rest of Castro’s planes were not to be attacked and the men fighting for their lives on the ground were to be left without air support that had been promised them.”

If the Kennedy administration’s handling of the Bay of Pigs invasion indicated that the administration was not as stridently anti-Castro as most Americans (including Oswald) thought, his concessions to the Soviets to settle the Cuban Missile Crisis reinforces that position.

In his review of Robert Kennedy’s book, Thirteen Days: A Memoir Of The Cuban Missile Crisis, in the March 1969 issue of American Opinion magazine (the predecessor to The New American) Professor Medford Evans noted:

The Bay of Pigs served as an enormous practical discouragement to any and all who might dream of overthrowing the Russian puppet Fidel Castro by invasion; the agreement with Khrushchev which ended the “missile crisis” put the United States Government in the position of legally guaranteeing Castro protection by American armed force if necessary against invasion from any quarter.

The point that Evans made is little known: Aside from removing our own missiles from Turkey (a member of NATO) in exchange for the Soviet removal of missiles from Cuba, a key part of the agreement was that the United States agreed to use U.S. naval power in the Straits of Florida to intercept any invasions of Cuba by Cuban exiles or anyone else. The resolution of the crisis was hardly a triumph of U.S. strength over Communist aggression.

While Killing Kennedy may have accurately reflected President Kennedy’s undeserved reputation as a strong opponent to Castro’s Communist regime — and the role that reputation played in fomenting Lee Harvey Oswald’s hatred of Kennedy — unlike the late radio commentator Paul Harvey, the movie failed by a long shot to tell us “the rest of the story.”

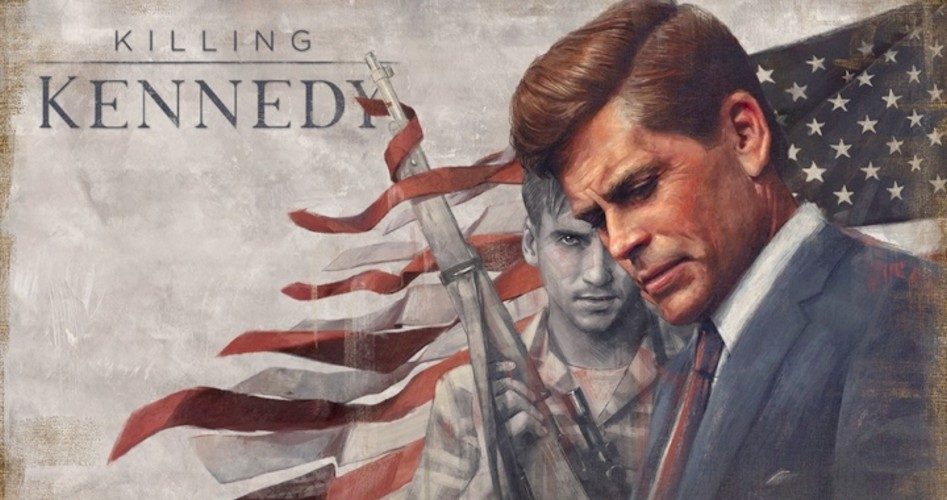

Graphic: movie poster

Related article: