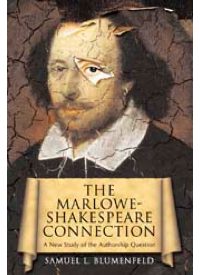

In The Marlow-Shakespeare Connection: A New Study of the Authorship Question, Samuel Blumenfeld undertakes the difficult task of proving an alternative author to the Shakespeare canon: Christopher Marlowe.

The Shakespeare authorship controversy began in 1781, when English clergyman Reverend James Wilmot claimed that Shakespeare, uneducated and inexperienced, was incapable of writing the greatest literary works of all time.

There have been several contenders under consideration for the title of “the real Shakespeare,” including Sir Walter Raleigh, Francis Bacon, Edward DeVere, and William Stanley. The Marlovian theory, that which claims Christopher Marlowe to be the true author of the Shakespeare canon, dates back as early as 1895. It is this group to which Blumenfeld belongs.

Stratfordians, on the other hand, argue that Shakespeare was the author of the canon. Despite the lengthy deliberations that have transpired and the persistence of the Marlovians, the Stratfordians continue to make up the majority in the debate.

According to Blumenfeld, the Stratfordians’ claim to legitimacy rests upon a minor reference in Greene’s Groatsworth of Wit, a “literary last will and testatment, written by Greene on his deathbed.” In this book, Greene “lashes out against those in the theater business who had used him and then left him to die in poverty.” In this text, Greene writes, “there is an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tygers hart wrapt in a Players hyde, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blanke verse as the best of you: and being an absolute Iohannes fac totum, is in his owne conceit the only Shake-scene in a countrey” (B.H. Blackwell, Oxford, 1919, pp. 72-73).

Stratfordians have seized upon this reference in Greene’s text as clear evidence that the “upstart Crow,” a term referring to one who borrows his/her ideas from others, is Shakespeare. For them, this is confirmed by the similarities between the words “Shake-scene” and “Shakespeare.”

Marlovians, on the other hand, claim that the “Shake-scene” in Greene’s text refers to the actor Edward Alleyn, a 26-year old who achieved great notoriety performing in many of Marlowe’s greatest plays, including Dr. Faustus and The Jew of Malta.

One grave weakness in the Marlovian theory is that Marlowe was murdered in 1593, while Shakespeare’s plays continued to be written and published well into the 1600s. However, Marlowe’s “death” has been another subject of major controversy, one that Blumenfeld tackles with a passion in his book.

There are three theories surrounding Marlowe’s death. The first claims that he was accidentally killed in a drunken brawl over a reckoning, or bill. The second argues that he was assassinated by decree of Queen Elizabeth, whom Marlowe served as a spy. The third theory, of course the one to which Marlovians assign belief, is that Marlowe’s death was feigned, to escape charges of heresy and sexual misconduct, which would have ultimately resulted in his execution.

Blumenfeld launches into a detailed speculation of the charges against Marlowe, strongly building a case that an enemy of Marlowe’s, the Earl of Essex, may have manufactured the charges. According to Blumenfeld, Robert Cecil, Thomas Walsingham, and Lord Burghley, men who were essential advisors to the Queen and men for whom Marlowe worked, feared what Marlowe would reveal under torture, and therefore formulated the plot for Marlowe’s staged death.

Blumenfeld cites the familial relationship between Lord Burghley and Eleanor Bull, the woman who owned the home at which Marlowe’s murder took place, as further evidence that the murder could simply have been a hoax. Additionally, Blumenfeld claims that the delay in the hanging of a John Penry only a few miles from Deptford, where Marlowe would be murdered, was scheduled so that Penry’s body could be used as Marlowe’s upon inspection by the coroner.

However, Blumenfeld’s proposed theory of the staged death weakens when he claims that actor Edward Allyn and Edward Blount, publisher of Shakespeare’s First Folio, supposedly knew of Marlowe’s phony murder. It seems hard to imagine that Cecil and Burghley would take such a risk as to involve these apolitical men in something as intricate and delicate as the staged death of Christopher Marlowe.

When Blumenfeld turns his attention to the analysis of Shakespeare’s works, he raises several interesting questions. For example, some of Shakespeare’s plays, including the Henry VI triad and Richard III, were much shorter in their Quarto versions than in the First Folio, published in 1623, seven years after Shakespeare’s death. This leaves Stratfordians with a difficult question to answer: Who revised the plays? Blumenfeld answers this by claiming that Marlowe was still alive, even after Shakespeare had died. Marlowe, being the author of the plays according to Blumenfeld, would be the only reasonable person qualified to edit his own works.

Blumenfeld, like most anti-Stratfordians, makes use of the lack of information recorded about Shakespeare as a means to justify that Shakespeare could not have written the plays. Scholars cite Shakespeare’s failure to mention any manuscripts or books in his will to justify the claim that he could not have been the author, since the plays reflect an author who had access to historical, political, and geographical sources. Yet Shakespeare seemingly had none.

While it is certainly reasonable to question the authorship of the plays, given the lack of historical documentation, the solution proposed by Marlovians leaves several questions unanswered.

First, if Marlowe was indeed the writer of the entire Shakespeare canon, why wouldn’t he have taken credit for the plays written prior to his “murder,” such as the Henry VI plays, which were believed to be written in 1591-1592?

Second, Marlovians often juxtapose the works of Shakespeare and Marlowe to cite continuity of style and close similarities in plot and characterization between the plays. While there is no doubt that Shakespeare referenced Marlowe incessantly in the writing of his plays, one has to ask: If the writers are the same, why have Shakespeare’s plays achieved a notoriety unparalleled by Marlowe’s works?

Despite the lingering questions, Blumenfeld’s book proves to be an intriguing read. His use of English history and close analysis of Marlowe’s plays are vital to the reader’s understanding of his theory, which is to convince the reader that Stratfordians have been duped for nearly 400 years. While it is not until Chapter 24 that Shakespeare and his plays begin to be addressed in any real depth, it is certainly worth the wait. Blumenfeld offers a little bit of insight into every one of Shakespeare’s works.

Like most works written on the subject of Shakespeare and the authorship of the plays, Blumenfeld’s work often makes use of speculative terminology: “perhaps,” “may,” “most likely,” etc. However, this will continue to be the case in any work on this subject until new major discoveries are made, if ever.

As noted by Blumenfeld, whoever wrote the plays will go down in history as the greatest writer of the English language. Some argue that it’s not important who wrote the plays, that they should simply be appreciated for their immortality. For others, like Blumenfeld, that simply isn’t enough.

The Marlow-Shakespeare Connection: A New Study of the Authorship Question, by Samuel Blumenfeld, Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2008, 368 pages, paperback. To order the book, click here.