The late Cardinal Francis George of Chicago predicted almost 10 years ago, “I expect to die in bed, my successor will die in prison and his successor will die a martyr in the public square.”

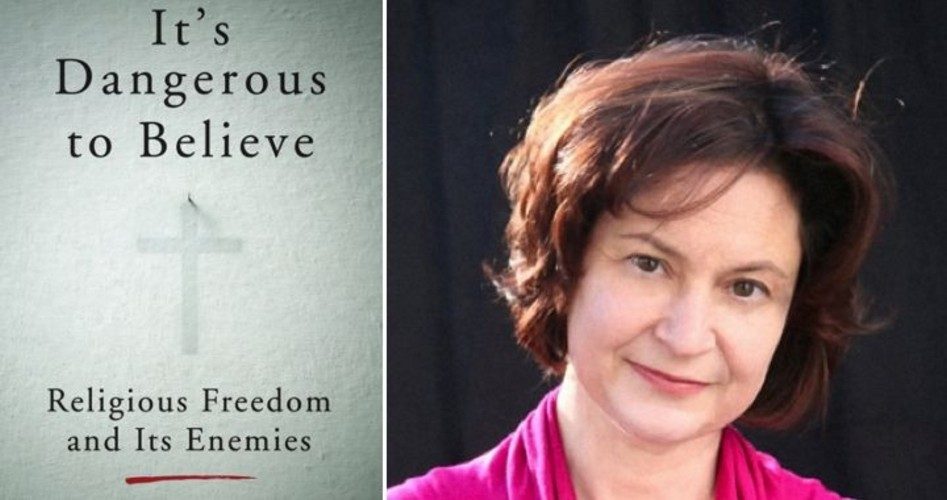

Such a grim prophecy of the fate of Christian leaders in the United States, long noted for its Christian culture, would have been met with derision by most believers just 20 years ago. But as author Mary Eberstadt (shown) says in her relatively short volume full of examples that tend to support the cardinal’s expectations of coming Christian persecution, “By 2016, in many influential cultural, political, and intellectual precincts, C for Christian has become the new scarlet letter.”

When young Alexis de Tocqueville traveled throughout America in the 1830s, he was struck by the pervasiveness of the Christian influence upon the culture. He attributed the greatness of the country — at which Europeans marveled — mostly to the churches, and predicted that as long as America remained a good country, it would remain a great country.

We have always had the “village atheist,” but few took him seriously. But now, this anti-Christian bias is growing exponentially, to the point that the whole “village” seems to be overflowing with atheists — or at least enemies of the Christian faith.

In Houston, Texas the mayor actually subpoenaed the sermons of five Protestant ministers, to determine if their words from the pulpit about sexuality ran afoul of a new city ordinance. An American military chaplain was reassigned due to his faithfulness to traditional Christian views. A Christian staffer was fired from working in a day-care center. The offense? Refusal to address a six-year-old boy as a girl.

These are not just random examples cited by Eberstadt. The idea that one’s Christian-oriented political views should not cost someone a job is no longer an accepted viewpoint among these militant anti-Christians. The creator of the JavaScript programming language, Brendan Eich, was fired from his job as CEO of Mozilla in 2014. His offense was that he had donated one thousand dollars to Proposition 8 in California, the ballot initiative that limited marriage to a man and a woman. Once this became public, Eich quickly got the boot.

Similarly, the fire chief of Atlanta was fired after self-publishing a Christian book to use in his Sunday School class. The problem was that a portion of the book declared that homosexual behavior was wrong, and despite his not having discussed these views on the job, it was an “offense” still considered worthy of termination.

Eberstadt has spoken with many younger Christians who fear they will not even be considered for a good job if they are seen to be “too” Christian. Even the aging and retired Baptist evangelist Billy Graham said last year that American believers should “prepare for persecution.”

How did America turn from a country where God and His people were honored, if not always emulated, to a nation that is just a few years behind the paganism sweeping Europe?

Eberstadt theorized that the assault upon the Christian faith began in some elements of the Enlightenment, and continued into the French Revolution (brought on by anti-Christian secret societies such as the Illuminati and the Jacobins). In the 19th century, the Darwinian evolutionary theory was used to attack the Christian religion. And, of course, the radical statist movements of communism and fascism were mortal enemies of religion as an impediment to their totalitarian goals.

Next, Eberstadt cited court decisions that contributed to the secularization of the public schools. She noted that the motion picture industry still made many movies with a Christian worldview in the 1950s (such as The Ten Commandments and The Robe); however, with the advent of the 1960s, Christianity came under attack in a series of movies — something that would have been unthinkable just a few short years earlier.

While she could have named a multitude of movies, she gave as examples The Da Vinci Code and The Life of Brian, both of which questioned the deity of Jesus Christ. The 1960 movie Inherit the Wind was among the first films to make a frontal assault upon Christianity, with agnostics and atheists such as H.L. Mencken and Clarence Darrow cast as heroes, and Christians such as William Jennings Bryan depicted as villains. As I demonstrate in a chapter of my book History’s Greatest Libels, this movie was full of historical inaccuracies, all designed to advance the plot idea that Christians were a detriment to progress in society.

Finally, after several years of this persistent undermining of the historic Christian faith, a “New Atheism” has arisen today — an atheism that is not content to live and let live, but is determined to bury Christianity under an avalanche of attacks. Eberstadt posits the thesis that one reason for the growing militancy of atheists is social media. According to this proposition, before the Internet many atheists felt isolated, but now they can interact with other such “free thinkers” on Facebook and Twitter, and are emboldened to make the most vicious insults of Christianity. It is unthinkable that Brendan Eich would have lost his position as Mozilla CEO had it not been for the agitation found on social media.

What harm can those who believe in a God who rules over the universe — a personal God who sent His Son to die on the cross for our salvation — present to these non-believers? After all, to paraphrase Thomas Jefferson, it doesn’t break their legs if Christians believe in Jesus Christ as the Second Person of the Trinity, does it?

It appears that this militant anti-Christian movement does fear Christians, or at least they say they do. Chris Hedges, writing in American Fascists: The Christian Right and the War on America, expressed fear of a “core group of powerful Christian dominionists who have latched on to the despair, isolation, disconnection and fear that drives many people into these churches.” Hedges insisted that American Christianity resembled fascist movements.

Kevin Phillips, once a respected Republican political analyst, argued in his book American Theocracy that “strong theocratic pressures are already visible in the Republican national coalition.” Damon Linker added his own salvoes against American Christians in his book The Theocons: Secular America Under Siege.

Of course, Eberstadt contends that this picture of theocracy — the belief that the Church should rule the world — is the opposite of what is actually happening. “The place at the table in Washington, D.C.” that “Christians experienced in the 1980s and early 1990s” — “that world is no more.”

But this image of an America ruled by Christian “theocrats” and “dominionists” is not just the loose talk of a few malcontents such as Kevin Phillips. Even if Christians are not considered a threat to force us all to submit to some Christian version of the Caliphate, they are seen as a convenient group to attack for political favor.

Who can forget when then-candidate Barack Obama dismissed evangelical Christians as “bitter[ly] cling[ing] to their guns and their religion,” adding that they were “less than loving.” Eberstadt asked if one could ever imagine this president referencing “less than loving Muslims”?

And it is not just the Democratic nominees of 2008 and 2012. This year’s nominee, Hillary Clinton, declared during her 2015 keynote speech at the World Conference on Women in China that “deep-seated cultural codes, religious beliefs and structural biases have to be changed.”

Ashley Samuelson McGuire of the Becket Fund wrote that “both President Obama and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton have been caught using the phrase ‘freedom of worship’ in prominent speeches, rather than the ‘freedom of religion’ the president called for in Cairo … Both the president and his secretary of state have now replaced ‘freedom of religion’ with ‘freedom of worship’ too many times to seem inadvertent.”

Certainly it was not “inadvertent” when Obama left the word “by their Creator” out when he quoted the portion of the Declaration of Independence which reads, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights.” Of course, if God is not the source of these rights, then government can simply take them away.

Who can forget when the delegates at the 2012 Democratic National Convention actually booed the inclusion of God in their party’s platform?

As Eberstadt said, Christians “are the only remaining minority that can be mocked and denigrated — broadly, unilaterally, and with impunity. Not to mention fired, fined, or otherwise punished for their beliefs.”

In 2014, the Christian group InterVarsity was kicked off 23 college campuses in California because it required its leaders to be Christians. Chi Alpha, a student organization affiliated with the Assemblies of God denomination, was de-recognized at California State, charged with “religious discrimination.” Their offense? They refused to open their leadership positions to non-Christians.

One negative about the book is that Eberstadt makes a few, brief comparisons to the attacks upon Christians as similar to the “McCarthy” era of the 1950s, implying that Senator Joseph McCarthy smeared “innocent” people. It is unfortunate that those such as Eberstadt use such comparisons, because McCarthy’s narrow interest was ferreting out Soviet spies who had widely infested the American government — especially the State Department. Unless someone believes that a spy for a hostile foreign power deserves a government job, McCarthy can hardly be faulted for wanting to rid our government of such individuals loyal to a system that had murdered millions of people — many of them Christians. It may well be that, while Eberstadt did extensive research in compiling the shocking incidents in her book, she may just have been repeating what she believed was that actual history of the 1950s. In my book History’s Greatest Libels, I devote a chapter to explaining how it is unfair to the historical Joe McCarthy to imply that he smeared “innocent” people.

Other than Eberstadt’s unfair characterization of the heroic McCarthy, this is a book I can highly recommend to all who treasure religious freedom.

It’s Dangerous to Believe: Religious Freedom and Its Enemies, by Mary Eberstadt, New York, New York: Harper Collins, 2016, 128 pages, hardcover.

Steve Byas is a professor of history at Randall University in Moore, Oklahoma.