In the forests, Jewish partisan groups operated, evading and attacking the German occupiers. But if escapees from the ghettos thought the forests and its denizens assured them of safety, they were wrong. The dangers of the forest were many: Germans, local collaborators, suspicious Russian troops, cold, disease, starvation, and even physical abuse from their own comrades. These are the stories of a partisan commander and a female partisan.

Genesis of a Partisan Commander

Yehuda Bielski knew precisely what he had to do. And he realized he had to act very quickly if he was to live.

Yehuda was a Jew trapped in the Novogrudek ghetto in Byelorussia during the summer of 1941. It became apparent to him that surviving a third “selection” — the process by which Hitler’s storm troopers (SS) decided which Jews lived or died — was unlikely. He refused to follow in the footsteps of family, friends, and neighbors who had taken the Third Reich’s one-way truck ride to the massacre pits outside Novogrudek, where Jews lay by the thousands side by side.

Yehuda knew that somewhere beyond the horizon of the barbed wire and wooden fences of the closely guarded ghetto was a refuge. Densely packed giant trees, wild vegetation, and dangerous swamps in the Byelorussian forest offered concealment from the Germans and their collaborators.

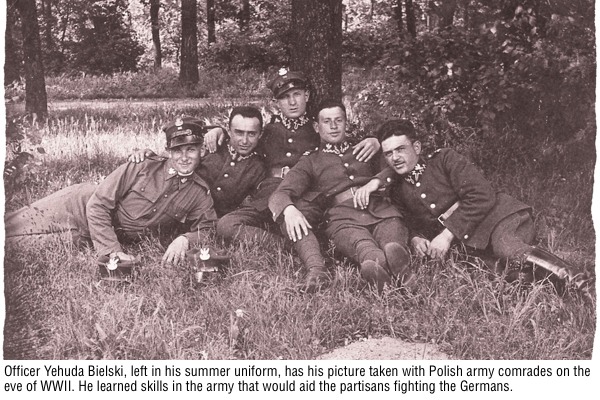

Yehuda’s war with Germany actually began two years earlier on September 1, 1939 when, as an officer in the Polish army, he defended his country on the western front.

Germany’s blitzkrieg left western Poland under German control within a month and sealed the fate of every Polish Jew under German occupation. Following Poland’s capitulation, a wounded Yehuda carefully maneuvered his way back into Soviet-occupied Eastern Poland, the area absorbed by Stalin as his spoils of the Molotov/Ribbentrop non-aggression pact.

On June 22, 1941, Operation Barbarossa shattered the temporary peace between Germany and the Soviet Union. The Wehrmacht (German army) and SS crossed the Russian/German demarcation border in Poland with two objectives: kill every Jew the Wehrmacht and SS could find and take Moscow as soon as possible. On the way to the Russian capitol, Germany reduced villages to rubble and ash, and massacred Jews or resettled them in squalid urban ghettos transformed into vast open-air prisons.

By early July the Wehrmacht took Novogrudek and converted it into two ghettos. Captive Jews were required to identify themselves by wearing the Star of David on their clothing and were stripped of their citizenship. All their money, property, and valuables were confiscated. In Novogrudek, Yehuda saw it all firsthand.

The world he had known as a child and young man had changed catastrophically. He had grown up with six siblings in this vibrant city where his father had been a successful glazier. He was educated in the city, and was also an athlete, played the violin and guitar, and became a noted ballroom dancer.

He spoke several languages, including Polish, Russian, Hebrew, and Yiddish. His skills, talents, and sophistication had been crucial in his becoming a Polish officer, and would now be pivotal for his survival.

By the end of July, the SS was in charge in Novogrudek. Selections occurred daily. The massacre of Jews was an SS priority. Certain that his time was up, Yehuda planned his life-or-death escape.

Set to flee, Yehuda received a letter delivered by a Christian friend, Konstantin Koslovsky, who had access to the ghetto:

Dear Yehuda,

We are hiding in the forest and we do not plan to submit to the Germans. Bring your wife, a few good men and we will build something together. Please do not hesitate. I hope to see you soon in the forest.

Your cousin, Tuvia

His older first cousin Tuvia, who was hiding in the forest with his three brothers and sister (all raised in a tiny nearby village) and about a dozen others, needed Yehuda’s expertise.

Yehuda quickly assembled a group of nine and led them to the fence surrounding the tightly guarded ghetto. They made a hole in the wood boards through which they crawled onto an open field and made it into the forest where Yehuda soon met up with his Bielski cousins.

One quick glance by the former officer revealed that the group was undisciplined and disorganized. Journalist Peter Duffy in his book The Bielski Brothers picks it up from there: “Soon after the arrival of the new members, a meeting was convened to discuss the group’s expansion…. Yehuda Bielski rose to speak. ‘We have come here into the forest, my dear ones, not to eat and drink, and enjoy ourselves,’ he said. ‘We have come here, every one of us, to stay alive.’ He then outlined a simple plan that pleased everyone: The goal is to find more weapons and strike at the invaders…. ‘We must choose a commander and give our unit a name,’ he continued.”

Yehuda then nominated Tuvia as head commander. The reason: the leader would have to do business with the Soviets and the treacherous NKVD (Stalin’s secret police) — which Yehuda had to avoid at all costs. Stalin, fearing that Polish officers would galvanize resistance against his takeover of Poland, had ordered them to be shot on sight.

Tuvia, 36, was enthused with his new leadership role. His 30-year-old brother Zus, whom Yehuda considered “a drinker who, when he was out of control with weapons, could be very dangerous,” was not happy. As a result, the two brothers’ bickering, reportedly begun before Tuvia assumed command, soon intensified.

Tuvia’s plan was to allow any Jew to join the Bielski partisans. Zus wanted to keep the group small, turning away Jews who escaped death in search of life. They also disagreed on the purpose of the camp. Tuvia wanted the group to be noncombative, avoiding contact with the Germans and locals in order to have the best chance of surviving. His brother insisted on doing battle with the enemy.

Zus eventually got his wish. He became the deputy commander of Ordzhonikidze, a Red Army/NKVD-controlled partisan unit that fought fearlessly and carried out acts of sabotage against the Germans. But as a result, the Poles saw him as their enemy for allying himself with the hated Soviet occupiers. Zus returned to the Bielskis in the waning days of the war.

The Bielski family group evolved into a fighting/family camp with an ever-growing community of escapees from ghettos and German roundups. Young and old, married and single, even orphaned children, were welcomed.

Commanding the Bielski partisans was an all-consuming responsibility. From the start, the partisans had to acquire weapons in order to defend the camp from the Germans and their collaborators. The partisans also needed food, medication, and especially clothing to overcome the brutal winters in the Byelorussian forest. If these necessities could not be purchased, armed partisans raided villages for their needs.

The partisans also obtained clothing from dead Russian and German soldiers. Uniforms provided warmth, but the German uniforms in particular proved to be valuable disguises for the partisans in their missions to obtain supplies.

Tuvia had challenges to his leadership, from his brother Zus as well as from other partisans. Insurrections could put the survival of the entire group in jeopardy.

Dealing with the Russians and the NKVD was especially tricky. Tuvia, who was not a communist, managed to convince the Russians that his partisans were not a threat to Stalin. As a result, the Russians airlifted supplies, including automatic weapons, into the camp. His relationship with the Soviets also enabled him to shield Yehuda from the NKVD.

Other Jews throughout Eastern Europe also hid from the Nazis in the forests. They too created family and partisan camps. The groups had much in common. Most of these Jews grew up in proximity to the forest where they would hide; they were familiar with the terrain and knew many of the locals, some of whom they could ask for help or understood to avoid.

The groups shared many challenges. They all needed weapons, food, clothing, medications, and other supplies. Women had special problems to overcome, from hygiene to pregnancy. The unique needs of children and the elderly presented extreme challenges. Religious members had to adjust to life without traditional dietary restrictions.

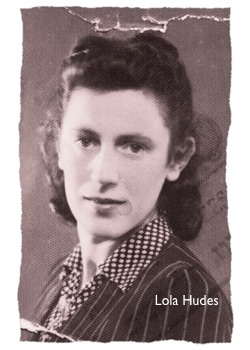

However, what distinguished one group from another was its leadership. The seclusion of the lawless forest meant that morality was subject to the decency or indecency of the camp’s  commanders. “The forest life changed no one,” observed Yehuda. “If a person was decent before the war, no matter what the situation in the woods, that person would behave properly. If the person was a low life before the war, he was a low life in the forest too. But in the woods he could take more advantage and get away with it.” Lola Hudes Bell, a member of four partisan groups including the Bielski partisans, agreed. “The woods had absolutely no effect on peoples’ values,” she recalled. “Fine people before the war would share their only slice of bread. A scoundrel before the war, who after a mission returned to our partisan camp with a whole loaf of bread, wouldn’t offer a hungry person even a crumb.”

commanders. “The forest life changed no one,” observed Yehuda. “If a person was decent before the war, no matter what the situation in the woods, that person would behave properly. If the person was a low life before the war, he was a low life in the forest too. But in the woods he could take more advantage and get away with it.” Lola Hudes Bell, a member of four partisan groups including the Bielski partisans, agreed. “The woods had absolutely no effect on peoples’ values,” she recalled. “Fine people before the war would share their only slice of bread. A scoundrel before the war, who after a mission returned to our partisan camp with a whole loaf of bread, wouldn’t offer a hungry person even a crumb.”

The most effective of all the partisan bands were the Bielski partisans of Byelorussia; no other group could claim to have saved over 1,200 Jews (Tuvia’s estimate) while losing only about 50 of its members. No group received such extraordinary fame as fearless fighters and rescuers. And no leadership was more controversial for its being connected to alleged war crimes against locals.

To this day, the Bielski name evokes strong emotions. Some Jews compare Tuvia to Moses for ordering his partisans to rescue them. And they laud his absolute determination in sheltering them and facilitating their survival against overwhelming odds. Some acknowledge with gratitude the protection Tuvia provided while at the same time recalling that his generosity could come at a price. Others remember Tuvia and Zus as absolute potentates who took advantage of women, and who as judge, jury, and executioner, decided the life and death of other Jews. And some survivors, remaining fearful of the tempestuous Bielski brothers, chose to have seen nothing, heard nothing, and known nothing.

Genesis of a Female Partisan

While the Bielski partisans were expanding their base, Lola Hudes was planning her escape from the nearby Stolpce ghetto.

Lola had come a long way to Byelorussia from her comfortable life in Lodz, Poland. Her father and oldest brother were importers. Another brother was a journalist and the third a student. One sister taught Polish and the other was a mother of three children.

Lola’s plans to attend university in France came to an abrupt halt when the Germans arrived in September 1939, renaming the German-speaking city Litzmannstadt. She soon fled east. Her fluency in German and Polish were instrumental during her journey on German military transport trains and later on foot into the Russian-occupied city of Stolpce in Byelorussia.

Safe for a short while, Lola was thrust back into the war by Operation Barbarossa. Stolpce soon became a German-occupied ghetto, and she was selected to work directly for the kommandant, thereby avoiding the massacre pits. Her language skills, including Russian, made her valuable as a translator and typist. Although working for the kommandant gave Lola some privileges and access to many areas forbidden to others, she understood that neither her duties nor the trust of the kommandant could earn her a pass from an eventual spot in a mass grave. Returning under guard every evening after her work at headquarters to a diminishing population in the ghetto convinced Lola that her luck would soon run out. She had only one option left.

“As I was planning my escape, Jakob and his brother Raffi [two young Jewish men] stopped by,” Lola recalled in her memoir One Came Back.

They had an escape plan and wanted to include me.… Raffi told me what he wanted.

“Lola, you have a pass that can get you to where the guns are kept. We need them when we will be hiding in the woods,” he said. “Are you out of your mind?” I asked. “You expect me to just walk into the room where the weapons are kept, take guns and bullets, hide them on me, and then with German soldiers walking up and down the corridors smuggle them back into the ghetto?” “Yes, Lola. You have to do it or we won’t have a chance to survive when we get out,” he said in a very matter of fact way.

“If I get caught, I’ll be shot on the spot,” I reminded him. “Lola, you are going to get shot anyway in a few days. So why not at least try to survive?” Jakob pointed out. We talked some more about how I could steal the weapons and bullets. Jakob’s idea was for me to sew some pockets into the inside of my coat and smuggle the arsenal out that way. After discussing it further, I was convinced that it was our only hope for a successful escape and survival in the woods.

We planned to flee the ghetto the following night, so I was under great pressure to get the weapons the following day. We were to meet at 10 o’clock by the ruins of a building.

But Lola’s work schedule the next day made it impossible for her to get into the arsenal storage room. She returned to the ghetto that night without the guns and ammunition. Jakob and Raffi, probably surmising that she had been caught because she did not show up at the agreed upon time, were nowhere to be found. So Lola fled the heavily guarded ghetto by crawling on her belly under the barbed-wire, avoiding the searchlights which lit up the field, and inched her way into the unknown forest.

The 21-year-old cosmopolitan woman wandered alone through a forest where she had never before set foot. Lola eventually joined two family camps and the famed Israel Kessler partisans, which later linked up with the Bielski group.

She recalled her first impressions of the place:

As soon as we arrived at the new camp, I immediately saw that it was a much larger operation with many more people. In fact, it appeared to be a community — almost like a small town.

We were sitting together as a group while Kessler was in conversation with several men from the other partisan group about their merger. “Bielski,” someone in our group whispered. And the name soon spread quickly. “That’s Bielski and his brothers,” said another man in my group as he pointed in the direction of the meeting. “Who is Bielski?” I asked. “You will soon find out,” Stefan, sitting near me, responded. Stefan did not look too happy.

It wasn’t long until I got a hint of what “you will soon find out” meant. Several men approached us. They wanted to know what items we had in our bundles, bags and knapsacks. One man took most of my underwear. In time, I would know him as Tuvia, the commander of the partisan group. I later found out that he gave my underwear to his girlfriend and sister.

Giving the Bielski brothers what they wanted, including money, watches, and jewelry was the price we all had to pay to become part of this group. And believe me, the brothers took whatever they thought could be useful to their families and girlfriends. They claimed that they needed our property to buy weapons and supplies, but an accounting after the war never took place to reveal if anything they took remained.

The camp was spread out in the woods where skilled people displaying tremendous energy were at work. The kitchen had large pots where potato soup was constantly cooking. There was a bakery with an oven. A bathhouse was constructed for washing and so that members could avoid getting typhus and other illnesses. A barber kept people reasonably neat. Shoemakers were making repairs. Tailors worked to sew old clothing and create new clothes, especially underwear which was in great demand by everyone. Carpenters built the work areas and the underground bunkers we slept in. A blacksmith took care of the partisans’ horses. A watchmaker repaired weapons.

A synagogue brought some members together for services and ceremonies, including funerals. There was an infirmary. Babies were delivered. Unfortunately, there were also abortions. For most, having babies in such a dangerous place and in such an unpredictable time was unwise. There was a dentist there as well. When children were not playing, they were educated by former teachers. Occasionally, there would even be shows performed by members of the camp. It was a village within the forest. And for those who violated the Bielski rules in this village, there was also a jail.

With no one to control them, Tuvia and Zus, especially when they were drunk, could be terrors. Tuvia and his two brothers made the law of the camp and everyone had to follow it. Zus liked to show off his gun displayed under his belt for everyone to see as he walked around the camp. But give him credit for being a real fighter which was important for our survival.

Amid the austerities and perils of camp life, Lola met and fell in love with Yehuda Bielski, who had lost his first wife to a German ambush before Lola arrived at the camp.

Life in the Bielski camp was constantly overshadowed by the danger of discovery by the enemy. Lola recalled one such lethal encounter:

One afternoon while I was knitting a woolen scarf, gunfire broke the relative quiet and calm of the camp. Germans in retreat from the east who were running for their lives through the woods stumbled upon the Bielski camp. The partisans and the Germans were in battle.

People ran for cover behind trees, rocks, and anywhere they could avoid being hit by a bullet. Still, bullets flew over my head hitting trees behind and around me. The partisans fought back valiantly, especially since they were taken by surprise when the Germans reached our camp. Explosions from hand grenades made the ground shake. The battle took about an hour, but it seemed as if I was behind that tree for days.

When the shooting stopped, I slowly and carefully walked back to our camp base. I was worried that some Germans may still be around and only be too eager to point their rifles at me and shoot. Many Germans lay dead on the ground. Closer to the base, partisans were removing their boots and clothing. They were also checking their gear for food or other items. All the weapons and bullets were placed in the center of the camp.

Soon I noticed a group of partisans standing in a circle. I could hear German being spoken. As I got closer, one of the partisans told me to leave the area. Minutes later I heard shots.

That evening Yehuda told me, “Lola, we captured two Germans. They were begging for their lives. They showed us pictures of their families, their children and parents. They weren’t very smart because they didn’t understand how we were looking for revenge after they killed our children and parents. We took off their shirts. One German had an SS mark on his arm so we killed him. The other we let go home,” concluded Yehuda.

Surviving the Holocaust

Well-armed partisans, prepared for battle, penetrated ghettos to rescue Jews. During one mission Yehuda was commanding, several residents of the ghetto were praying while Yehuda urged them to immediately leave with him and his men. God would save them, they insisted. Yehuda held up his weapon and responded, “With all respect to God, this is the only thing that will save you here.” Those who refused to leave with the partisans were eventually killed. Those who joined Yehuda survived.

Upon “liberation” by the Soviets in 1944, the Soviets told the partisans that they were now free to march out of the forest and make their way to their homes. The war was over for them.

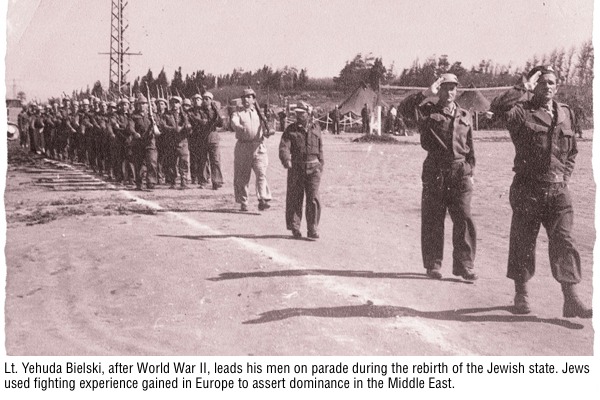

The survivors from the Bielski camp embraced life. Yehuda married Lola and, like many other surviving partisans, went to Palestine to fight for a Jewish state. Yehuda was welcomed by the Irgun, a militant underground organization formed to defend Jews against Arab terrorism and push the British out of Palestine. In 1948, Yehuda, unlike his commander cousins, was commissioned an officer in the IDF (Israel Defense Forces) and fought with distinction in the War of Independence.

Yehuda, Lola, and their two children — one of whom is the author of this article — came to America in the 1950s. Yehuda’s cousins with their families followed. Today, the descendants of the Bielskis and of the approximately 1,200 people who survived the war in the Bielski camp number many thousands.

Earlier this year, Hollywood released the theatrical movie Defiance that tells (unfortunately, with a number of inaccuracies) the story of the Bielski brothers.

With stories emerging about the Bielskis varying wildly, an admonishment from William Shakespeare: “This above all: ‘To thine own self be true, and it must follow, as the night the day, thou canst not then be false to any man’” (Hamlet, act 1, scene III).

Y. Eric Bell is a graduate of the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law and a television producer/director. He is the son of the late Lola and Yehuda Bell (formerly Bielski).

All photos herein appear, with permission, from the Yehuda & Lola Bell Collection.