“Presidents’ Day,” as it is now commonly called, retains some vague connection to Washington’s birthday, if only for the purpose of advertising “Washington’s Birthday sales.” The traditional birth date of February 22 has been stretched to create a Monday holiday — this year on February 18 — to accommodate America’s patriotic devotion to three-day weekends.

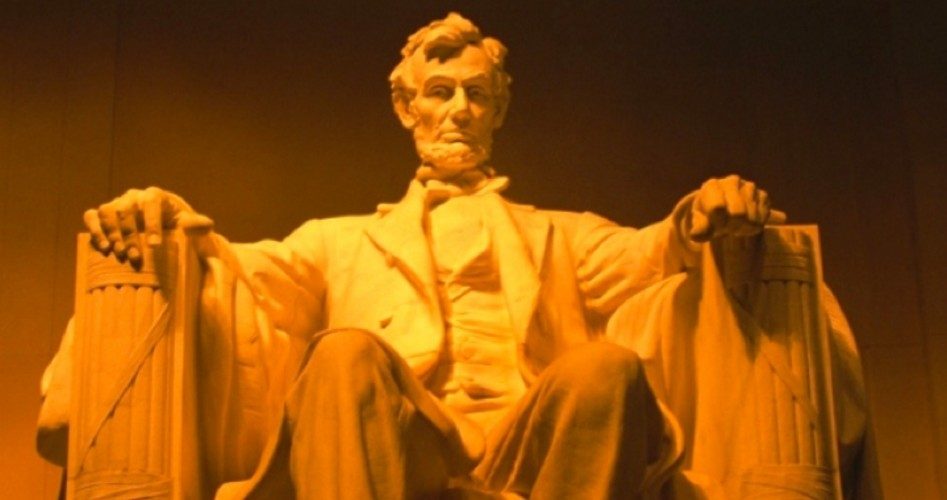

But Lincoln’s birthday, February 12, appears to have lost some of its former aura, since all presidents are now supposedly covered by the amorphous, all-purpose “Presidents’ Day.” (Let us now praise Millard Fillmore.) That is ironic, because despite the energetic work of some recent revisionist historians, Lincoln remains the most revered — some say “deified” — of all our presidents. Historians have repeatedly ranked him the greatest U.S. president, with FDR coming in second.

Both were wartime presidents, dealing with crises that threatened the very survival of the nation. The nation survived, and the presidents have received the glory, since those who died in the battlefields — who gave, as Lincoln put it, “the last full measure of devotion” — are too numerous to remember. The presidents were the managers of the winning teams, but as Yankees manager Casey Stengel said after his seventh World Series win in 10 years, “I couldn’t ‘a’ done it without the players.”

Politicians are not saints, at least not in our time. Yet Ambrose Bierce’s definition of a saint in his Devil’s Dictionary applies to politicians as well: “A dead sinner, revised and edited.” That seems especially true when the sinner has died while serving in the nation’s highest office. Both Lincoln and Roosevelt died while in office, though death came to Lincoln in far more sudden and dramatic fashion. Roosevelt had sought and won the office so many times that awaiting his death seemed the only “exit strategy” available to Republicans in exile. Though others died in office, the term “President for Life” could be fittingly used to describe only one American head of state.

Dying in office does not necessarily make a president “immortal,” however. Few today wax nostalgic about Harrison, Garfield, or McKinley, and the Harding administration is remembered mainly for the Teapot Dome scandal. But Lincoln’s death, like that of John F. Kennedy, turned out to be what one commentator called Elvis Presley’s passing: “a good move, public relations-wise.” Few remember that Lincoln, like Kennedy, was elected by a minority of those voting. The late columnist Joseph Sobran noted ironically that Lincoln’s greatness, now considered virtually indisputable, went largely unnoticed by his contemporaries.

“The abolitionists considered him unprincipled,” Sobran wrote. “Southerners hated him, and most Northerners opposed his war on the South. Only when the war ended and he was shot did people begin to transform him into a hero and martyr of the Union cause.”

Thus Lincoln paid a high price for his glory. Had he lived to serve out his second term, would the history of the last third of the 19th century in America have been noticeably different, perhaps even better? Though Lincoln was hated in the Southern states that his generals bludgeoned, pillaged, and burned into “unconditional surrender,” his attitude toward the Confederacy appeared markedly different from the “radical Republicans” who impeached Andrew Johnson and treated white Southerners as a subjugated people in an occupied nation. Lincoln, recall, promised at his first inauguration to leave untouched the institution of slavery where it existed and to refrain from invading the Southern states so long as the rebels respected federal property, including military installations, and paid imposts and duties to the Union government he regarded as still the legitimate government over all the states.

Though he opposed the expansion of slavery, he was neither an abolitionist nor a promoter of racial equality. He publicly stated he did not believe in equality of the Negro with the white man and did not believe the black brethren should be permitted to vote, hold office, or serve on juries. Lincoln was a politician, and he would no doubt have bent to accommodate the radical Republicans on some points. But it is hard to imagine him going along with the Reconstruction scheme of installing suddenly freed and uneducated slaves in high political office.

The Civil War and its aftermath left what were once “these United States” with an enlarged and consolidated federal government. Increasingly, parts of Jefferson’s description of British tyranny in the Declaration of Independence would come to be quoted as an apt description of our own government in Washington. Would the colonists have rebelled against “taxation without representation” if they had known what taxation with representation would be like? The British king, the Declaration charged, had created “a multitude of new offices” in what we might now recognize as a dress rehearsal for Roosevelt’s New Deal. He had “sent hither swarms of officers to harass our people and eat out their substance.” And that was long before we had an income tax and the Internal Revenue Service!

Lincoln claimed he had never had a political sentiment that was not inspired by the Declaration of Independence. Surely, what have been called that document’s “glittering generalities” about freedom and equality inspired much of Lincoln’s lofty rhetoric. But to the main argument of the Declaration, the asserted right of one people to separate themselves from another and establish their own governments, Lincoln was implacably opposed, at least as it was claimed by the Confederate States of America. Lincoln refused to recognize either the right or the fact of secession, insisting on calling the uprising in the South a “rebellion,” rather than secession. And deeming it a domestic rebellion, not a war, he saw no need to go to Congress for a declaration of war.

Lincoln authorized his generals to suspend habeas corpus and he imprisoned without trial many noncombatants, including Northern editors and publishers who opposed the war against the Southern states. Interestingly, that has done little, at least until very recent times, to diminish his reputation. Newspapers and other media have often been regarded as impediments to “good government.” Evidence of Napoleon’s greatness, wrote one sociologist, was the fact that he once had a publisher shot.

Lincoln was a brilliant rhetorician and a magnificent orator — among the greatest, if not the greatest, in our nation’s history. But he was neither the first nor the last president to stand truth and logic on their old gray heads.

Related articles: