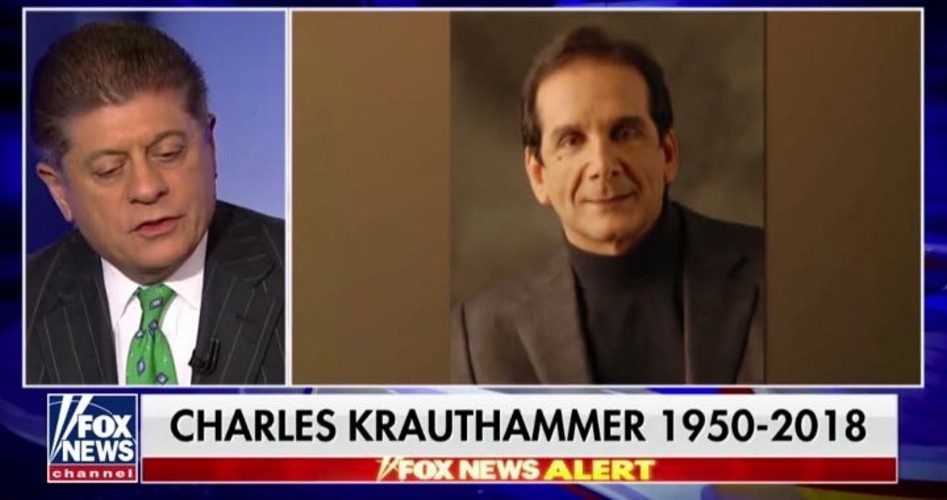

Bill Clinton once called Charles Krauthammer (shown on right) “a brilliant man,” to which Krauthammer lamented that his commentator career was now “toast.”

This was but one example of the dry wit that endeared him to the many who followed him in his column, which appeared in over 400 publications, or listened to his intriguing analysis on Fox News. When informed that the cancer that he had battled for about a year was going to defeat him, he wrote a final column, in which he said, “I leave this life with no regrets. It was a wonderful life.”

Krauthammer’s remark that he had experienced a “wonderful life” is remarkable, considering the diving accident during his first year at Harvard Medical School that left him permanently paralyzed from the neck down. Ironically, as he recalls, “There were two books on the side of the pool when they picked up my effects. One was Anatomy of the Spinal Cord.”

Discussing his paralysis years later, he said he did not want that to characterize his life. “I don’t want it to be the first line of my obituary. If it is, that will be a failure.” Following the accident that nearly killed him, he drove himself to make sure that his paralysis would not be his most remembered feature. After 14 months in the hospital, he returned to medical school, graduating to become an accomplished psychiatrist.

But he left the world of psychiatry to become a well-known political commentator. “America is the only country ever founded on an idea.… It’s founded on an idea and the idea is liberty,” he once remarked.

Such sentiments created fans among conservatives, but early in his career he was a speechwriter for Walter Mondale, hardly an icon for conservatives. But as time went on, Krauthammer became increasingly conservative, and he explained the transition: “I was a Great Society liberal. I thought we ought to help the poor, we ought to give them all the money we can. And then, the evidence started to pour in. The evidence of how these grand programs, the poverty programs, the welfare programs — everything was making things worse .… As a doctor, I’d been trained in empirical evidence. If the treatment is killing your patients, you stop the treatment.”

Krauthammer was one of those often referred to as “neoconservatives.” But unlike fellow neocon Bill Kristol, who is perhaps the personification of arrogance, he did not tend to inflame the passions of more traditional conservatives in the same way. Brit Hume, his colleague at Fox News, explained: “Krauthammer delivered his views in a mild-mannered yet steady and almost philosophical style, befitting his background in psychiatry and detailed analysis of human behavior.”

Writing in the Washington Post in 2014, he tackled the issue of “climate change,” objecting to declaring global warming settled science, saying that so much is believed to be settled that turns out not to be so. Some of his remarks defied labeling, such as when he said of the abortion issue, “I do not believe that personhood is conferred upon conception. But I also do not believe that a human embryo is the moral equivalent of a hangnail and deserves no more respect than an appendix.”

While Krauthammer’s views can be generally categorized as conservative, it was in the field of foreign policy that those on the more traditional Right would object — views that no doubt landed him a membership in the globalist Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). He believed the United States had a responsibility to be interventionist, although he sometimes differed with his neoconservative allies (such as Kristol) who advocated an interventionist policy of “American greatness.” He wrote that, in the absence of a global existential threat, the United States should stay of out “teacup wars” in failed states. He specifically opposed American intervention in the wars in Bosnia, arguing that America had no business sending its soldiers to die in an area in which no vital American interest was at stake.

In fact, he lectured his fellow neoconservatives while accepting the Irving Kristol Award in 2004: “We will support democracy everywhere, but we will commit blood and treasure only in places where there is a strategic necessity — meaning, places central to the larger war against the existential enemy, the enemy that poses a global mortal threat to freedom.”

But in that same Irving Kristol lecture, he demonstrated that he was no traditional conservative in foreign policy. “Isolationism originally sprang from a view of America as spiritually superior to the Old World. We were too good to be corrupted by its low intrigues, entangled by its cynical alliances,” he said.

“Today, however, isolationism is an ideology of fear. Fear of trade. Fear of immigrants. Fear of the Other. Isolationists want to cut off trade and immigration, and withdraw from our military and strategic commitments around the world.… They [non-interventionists, called “isolationists” by the interventionists] are for a radical retrenchment of American power — for pulling up the drawbridge to Fortress America.”

Krauthammer allowed that “isolationism” was an acceptable political viewpoint — at one time in our history. “Isolationism is an important school of thought historically, but not today,” he argued.

As such, his support of the 1991 Gulf War, asserting that he wanted to keep Saddam Hussein from gaining control of the Persian Gulf and his backing of the 2003 Iraq War, believing the Bush administration’s assertions that Hussein had large stocks of WMDs, is not surprising. While Krauthammer often supported conservative views in domestic politics, it should be recognized that it is contradictory to support limited government in domestic matters, while supporting globalist interventionist policies abroad.

Multilateral trade deals and international alliances such as the UN and the WTO inevitably lead to less national sovereignty for America. In the end, it is perplexing for neoconservatives such as Krauthammer to argue for “American Exceptionalism,” yet support entangling alliances that Founding Fathers such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson feared could end our nation’s hard-won independence.

Krauthammer did not follow the Orthodox Jewish beliefs of his parents, but he was not an atheist, referring to atheism as “the least plausible of all theologies. I mean, there are a lot of wild ones out there, but the one that runs so contrary to what is possible, is atheism.”

Before his diving accident, he married and had a son. They both survive him. He was 68.

Image: Screenshot of a Fox News Youtube video