Breslin would win a Pulitzer Prize in 1986 for "columns which consistently champion ordinary citizens." That makes his 1963 book about the "amazin’ Mets" all the more exceptional. The gravedigger at Arlington may have been an ordinary citizen. But New York Mets of 1962 were no ordinary ball club. They weren’t nearly that good.

But "ordinary citizens" loved them, which is why Breslin’s chronicle of the Marx Brothers of baseball, those "loveable losers" of baseball lore, is his best known and best loved book, though he has authored nearly two dozen. Samuel Johnson would no doubt be appalled at the comparison, but Jimmy Breslin became the Boswell of the ’62 Mets.

The saga began 50 years ago this day. It was on April 11, 1962 that the New York Metropolitans of the National League took the field for the first time in a regular season game. They came in that year, along with the Houston Colts (later Astros) as an expansion team, as the league went from eight to ten teams. The established teams had to discard players to form a pool from which the newcomers could draft players their former employers deemed the most expendable. The Mets, bringing National League baseball back to the Big Apple after both the Giants and Dodgers had deserted New York for the Gold Coast, drafted players with familiar names, including former Brooklyn Dodgers stars Gil Hodges and Charlie Neal and former Giants catcher Hobie Landrith, the first player drafted by the Mets. You’ve got to have a catcher, Casey explained, "Otherwise you’ll have a lot of passed balls."

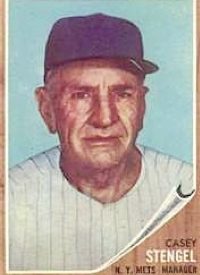

The assemblage of name players, whose skills had largely deserted them, was joined by several unknowns whose skills might never be discovered. And so it was that the legendary ineptitude that became the intriguing story of the 1962 baseball season showed up early in spring training, when Stengel, who had managed 10 pennant winning and seven World Champion teams in 12 years with the New York Yankees, surveyed his new charges and announced: "Yes, sir. Come see my amazin’ Mets, some of which has never played semi-pro before."

Billy Loes, a former Dodgers pitcher who once managed to lose a ground ball in the sun, was one of the players drafted by the Mets. Loes saw baseball’s expansion as a logical extension of the New Deal. "The Mets is a very good thing," he said. "They give everybody a job. Just like the WPA." New York restaurateur Toots Shorr also drew a comparison to the 1930s. He made his son watch the Mets lose game after game, he said, so the lad would know what the Depression was like.

No one quite knew what to expect when the Mets opened their inaugural season at Busch Stadium in St. Louis. No one was too surprised when they lost that first game, but when they lost the next nine, people began to wonder. Fortunately, they had Stengel to explain things, as when a simple pop up eluded several of his fielders. "The wind got a holt of it," the manager explained. "Otherwise my mind tells me my players would be running toward the ball instead of away from it." At other times he could only watch in stunned disbelief. One game ended when a ground ball back to the mound got by the Mets pitcher, two infielders and the outfielder who overran it, leaving the manager staring out at the field and wondering how a simple ground ball could be so fiendishly clever at escaping capture by a team of (more or less) major league ball players!

The team’s signature player was "Marvelous Marv Throneberry," a first baseman whose fielding flaws were exceeded only by his base running errors. Once, when proudly perched on third with an apparent triple, Throneberry watched helplessly as he was called out at first for missing the base. When Charley Neal followed by hitting the ball over the left field fence, Stengel sprinted out of the first base dugout as fast as a man of 72 years could sprint. Reaching the first base coach’s box as Neal was easing into his home run trot, Stengel pointed emphatically to the bag. As Neal rounded the bases, the manager pointed to each one to make sure the runner found each base in the broad daylight. Casey was taking nothing for granted.

Meanwhile, in the Bronx, the pinstriped Yankees were winning another pennant, something they did with monotonous regularity. The Mets were, well, different. "This was not another group of methodical athletes making a living at baseball," Breslin wrote. "Not the Mets. They did things." Like win a game once in a while, an average of one in four. But it’s not like they weren’t trying in the other three. That’s what made them so endearing to so many fans. Like most of us, the Mets had to struggle for even modest — okay, rare — success. The Yankees’ lineup of legends, with the likes of Mantle and Maris, Berra, and Ford dominating a league of mere mortals, had become a boring tale. The Mets were real people, struggling against real adversity and if they lost in improbable ways, well, life and baseballs take improbable bounces. People saw that in their own lives. And they saw it in the Mets.

But the appeal of the "loveable losers" has its limits. In the end we want a fairy tale. The Mets provided that as well. Just seven years after launching the franchise with the worst season of any team in the 20th century, and only one year after finishing in ninth place, the "Miracle Mets" won the pennant and the World Series, proving once again the Old Professor was right.

"They say you can’t do it," Stengel said, "but sometimes it isn’t always true."

Photo: Casey Stengel as depicted on a 1962 Topps baseball card.