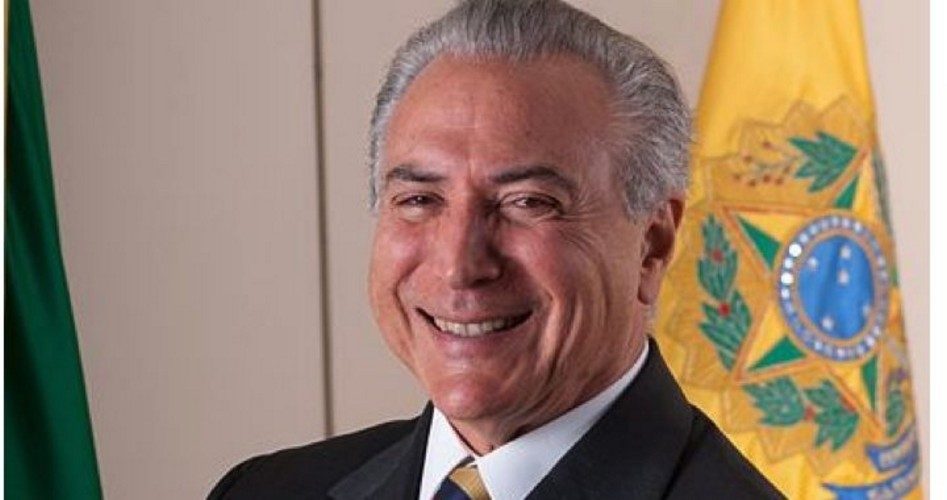

Just after being sworn in as Brazil’s new president, and just before jetting off to the G-20 meeting in China to hobnob with the global elites, Michel Temer (shown) took time on Wednesday to make a promise to Brazilians: “From today on, the expectations are much higher for the [new] government. I hope that in these two years and four months [when his term ends in 2018], we do what we have declared: put Brazil back on track.”

That’s an expression more of hope than reality: Little is likely to change except the name of Brazil’s president. Temer faces challenges that would stagger Godzilla:

• An economy that has shrunk by more than 10 percent in just the last five years, with few expectations that it will get better;

• Inflation that is currently running at one percent a month;

• Unemployment pushing double digits;

• An approval rating just as low as those of Dilma Rousseff, just ousted from the presidency;

• An administration rife with political cronies, three of whom have been forced to resign just since May on corruption charges (one of whom was named as Temer’s “anti-corruption” minister); and

• A Congress filled with at least 50 politicians implicated in the Operation Car Wash/Petrobras scandal.

Temer is facing personal challenges, as well, including suffering punishment for violating campaign finance laws in his 2014 election, keeping him from running for political office for eight years, charges that he channeled $400,000 in Petrobras kickbacks to one of his cronies running for mayor of Sao Paulo, and other charges that he paid off a construction executive some $300,000 in a bribe also related to the Petrobras scandal.

In addition, an electoral court is currently investigating Temer’s role in the 2014 election scandal, which could result in new elections to replace him long before his term ends at the end of December 2018.

So far, his record as a “center-right politician,” a “moderate,” and “pro-business, free-market advocate,” as mythologized by the mainstream media in the United States, belies such claims. Shortly after becoming Brazil’s interim president while Rousseff was being tried by the Senate, Temer arranged a $1 billion bailout of Rio to pay for the Olympic Games’ infrastructure, and instituted massive wage increases for government workers. This occurred while Brazil is struggling with a national debt nearly equal to the country’s total economic annual, output which has forced rating agencies to declare its bonds as junk.

In addition, Temer named the former head of the country’s central bank as his chief economic advisor, hardly a harbinger of big changes coming from his administration.

The New York Times characterized Rousseff’s ouster and Temer’s inauguration as putting “a definitive end to 13 years of governing by the leftist Workers’ Party,” while the Wall Street Journal called Temer’s new administration a “new start.”

As head of the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB), Temer has hardly distanced himself from his party’s ties to socialist and communist parties with which the PMDB has worked closely since its beginning.

PMDB has a long and sordid record of vote-buying and corruption, dating back to at least 2005 when the Mensalão scandal broke. It almost toppled the administration of Brazil’s President Lula da Silva when the investigation revealed that the PT Workers’ Party, included under the PMDB’s “big tent,” was buying off a number of legislators with payments of $12,000 every month in exchange for favorable votes.

What Temer should do is cut taxes and regulations, lay off thousands of government bureaucrats, and cut the wages of those remaining in essential positions. He should create and then enforce a balanced budget, and install ministers who understand the dangers of central banking and the advantages of a free market.

None of that is likely to happen, of course, despite the New York Times’ claim that Temer’s new administration “closes 13 years of rule by … the leftist Workers’ Party.” What the new beginning represents is likely to be a continuation of the policies that sank Brazil’s economy to the bottom. Those Keynesian economic “solutions” included easy credit, energy subsidies, and other “stimulus” measures designed to end Brazil’s economic stagnation. Instead they made matters worse. The economy moved from 7.6 percent growth in 2010 to a 3.8 percent contraction last year — an 11 percent shrinkage — with expectations that it will shrink another 3.2 percent this year.

It is said that if nothing changes, nothing will change. Temer is a continuation of the crooked politics and bankrupt economic policies that have been foisted upon Brazilians for the last 17 years.

A graduate of an Ivy League school and a former investment advisor, Bob is a regular contributor to The New American magazine and blogs frequently at LightFromTheRight.com, primarily on economics and politics. He can be reached at [email protected].

Related article: