Estimates that price inflation in Venezuela is running between 10 and 20 percent a month are too low if one looks at the black market there. By putting price controls on essentials such as personal care items and medicines, President Nicolas Madura, a protégé of Marxist Hugo Chávez, Venezuela’s previous president, has guaranteed at least two things: shortages and rationing. A healthy but very expensive black market has sprung up to meet consumer needs for items such as chickens, medicines, and toilet paper.

In that black, or free, market, Venezuelan women were shocked to find that the price of tampons and other sanitary supplies jumped 1,800 percent, while other hapless citizens caught in Madura’s socialist paradise have seen prices for other necessities exceed five times the government controlled prices, if they can be found at all.

In June the price of a basic food basket jumped 19.9 percent, while clothes and cleaning products are being priced out of reach for most consumers. Those government limits are hampering the ability of doctors and hospitals to care for the ill, or those wounded in battles with Madura’s police during protests. The president of Venezuela’s Medical Federation, Douglas Leon Natera, said: “Doctors are working with our bare hands, without resources.” Patients coming to hospitals are being urged to bring their own disinfectant, gauze, bandages and painkillers.

All because of price controls that keep factories that make them from selling them profitably. Rather than sell them at a loss, they stop selling them altogether.

The black market is helping to relieve some of this distress. For example, Denise Contreras, who lives in Miami but is trying to provide care for her 80-year-old mother who lies disabled in a San Cristobal nursing home bed, has set up a chain of helpers stretching from Miami to Colombia to Venezuela, getting her mother diapers, toiletries, and nutritional shakes that aren’t available there.

USA Today told the results of such governmental interferences:

The result of the scarcities has been tragic, with allegations of patients dying and doctors even forced to carry out needless mastectomies because they can’t access other means to treat breast cancer.

As the price of oil has dropped, so has the government’s revenue stream, with the country’s central bank printing bolivars to cover the widening deficits. When the supply of something increases, the value of each unit declines. The same happens with currency. When the value of a currency declines far enough, fast enough, it’s called “hyperinflation.” By definition, hyperinflation happens, according to Phillip Cagan, a professor at Columbia University, when prices rise at or above the rate of 50 percent a month, or they double every two months or less. If not already there, Venezuela is getting close.

None of this was supposed to happen, of course. In his op-ed published by the New York Times in April 2014, Maduro spoke proudly of how his continuing socialist revolution has resulted in “the lowest income inequality in the region,” adding: “We have created flagship universal health care and education programs, free to our citizens nationwide.”

His answer to some of the problems created by those price controls:

While our social policies have improved citizens’ lives over all, the government has also confronted serious economic challenges … including inflation and shortages of basic goods.

We continue to find solutions through … monitoring businesses to ensure [that] they are not gouging consumers or hoarding products.

Venezuela has also struggled with a high crime rate. We are addressing this by building a new national police force … and revamping our prison system.

A year later, in May, the economic situation had continued to deteriorate, and Maduro had the same answer. As Tim Worstall noted in Forbes:

Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro has promised to nationalize food distribution in the South American nation beset with record shortages of basic goods, runaway inflation and an escalating economic crisis.

This will fix nothing, but instead make things even worse, if possible. But it’s all for the glories of the socialist revolution: One can’t make an omelet, it has been said, without breaking a few eggs. Madura’s vice president, Jorge Arreaza, explained:

We have built a model and it’s irreversible. We are constructing socialism, which is real democracy. We are going to build it because that’s the legacy President Chávez left us.

And we’re not just building it here, but in Latin America and probably in the rest of the world.

There’s no “probably” about it, Mr. Arreaza. By adopting similar strategies to solve similar problems in the United States, socialist politicians are traveling down the same path. As Abigail Hall, writing for the Independent Institute about the unfolding Venezuelan disaster, put it: “The difference [between the United States and Venezuela] is one of degree, not of kind.”

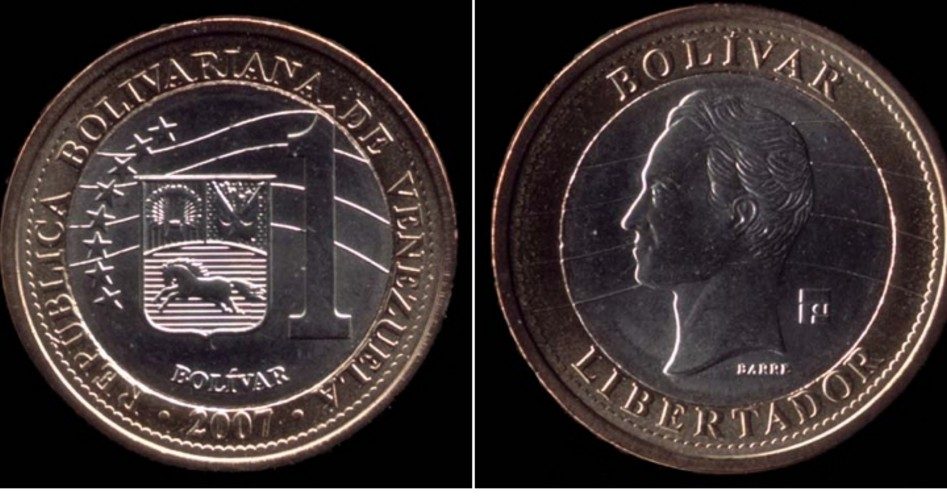

Photo of bolivar currency: JesusElGuaro

A graduate of an Ivy League school and a former investment advisor, Bob is a regular contributor to The New American magazine and blogs frequently at www.LightFromTheRight.com, primarily on economics and politics.