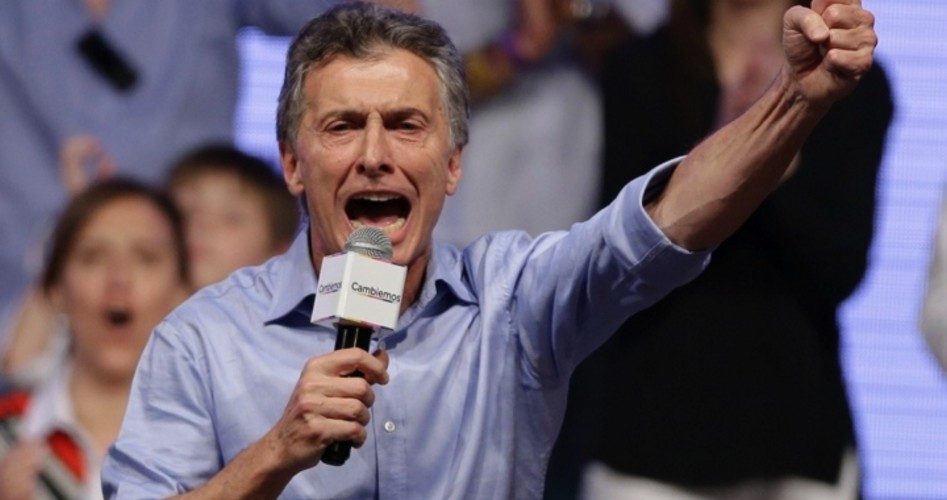

Weary of years of corruption, repression, and economic malaise under hard-Left president Cristina Fernández, Argentines have elected conservative Mauricio Macri (shown), businessman, two-term former mayor of Buenos Aires, and sometime owner of one of Argentina’s two most popular soccer clubs, Boca Juniors.

The Argentine economy has been reeling from the effects of a default on government debt — Argentina’s second in the last 15 years — and from repressive currency controls imposed by the dictatorially-inclined Fernández. With inflation running over 20 percent and roughly one fifth of the entire government budget allocated to subsidies, Argentina will have to take tough medicine to remedy one of the most intractable economic crises in history.

Macri is only Argentina’s third president since 1983 not to have belonged to the country’s Peronist party. For generations, Argentina has been addicted to welfare-state programs and the massive public debts that they unavoidably entail, making this beautiful and formerly wealthy South American nation a poster child for political instability and chronic inflation. When this author was living in Argentina in the late 1970s, inflation was running at 100 percent or more. Argentines did not save money; instead, they purchased real estate, foreign currencies, precious metals, and any other assets that retained value.

In the early 1980s, the military junta fell after the failed invasion of the Falkland Islands, and Argentina restored popularly-elected government.

But old habits die hard. Over the ensuing three decades, Argentina has not relinquished her embrace of socialism, causing debts to spiral higher and higher and inflation to continue taking its toll on what was once one of the world’s largest economies.

In December 2001, after an acute depression of almost four years, Argentina finally defaulted on its massive foreign debt. At the time, the default represented about one seventh of all debt owed by the developing world.

In the years since, the combative leftist Argentine presidents Nestor Kirchner and his widow, Cristina Fernández, managed to bluff their way (temporarily) out of the debt crisis by negotiating settlements with some of their creditors and rebuffing the others. For a few years, Argentina appeared to be on the mend.

But Argentina’s socialist policies caused new debts to pile up. Cristina Fernández, instead of proposing spending cuts and downsizing the country’s gargantuan public sector, placed all the blame for the country’s misfortunes on wicked “vulture” capitalists overseas. The xenophobic rhetoric played well — for a while. But eventually, Argentina’s economy worsened to the point that Argentines were again hiding their assets in foreign accounts and carrying out transactions in U.S. dollars. The desperate response of the Fernández government was to impose strict currency controls, which forbade citizens from acquiring dollars or taking other actions to avoid using Argentine pesos — and created a huge black market in U.S. dollars.

After several years of currency controls and deepening economic malaise that included a second default last summer, Argentines appear to be finally fed up. Having defeated Daniel Scioli, Fernandez’s handpicked successor, Macri appears to have broad public support for a new economic direction that may involve lifting of currency controls and a return to the bargaining table with foreign creditors so as to once again open global credit markets.

The true state of Argentina’s economy is probably much worse than advertised, since the Fernández administration is widely believed to have manipulated economic data to conceal inconvenient truths. Cristina Fernández, a hardline doctrinaire socialist (and friend of Hillary Clinton) made herself unpopular both at home and abroad for her abrasive, histrionic style of leadership, blaming all of her and Argentina’s woes on foreigners and greedy financial capitalists.

Mauricio Macri’s honeymoon with the Argentine public and with lawmakers is likely to be short-lived, as Argentines discover the price to be paid for so many years of public profligacy. Whether he can succeed where previous would-be reformers, such as Raúl Alfonsín and Fernando de la Rúa, failed, remains to be seen. It is worth noting that neither Alfonsín nor de la Rúa finished their respective terms in office, with Alfonsín resigning six months early with hyperinflation consuming the economy and de la Rúa fleeing by helicopter from the presidential residence as angry mobs raged and rioted outside. The reforms being contemplated by Macri and his allies are sure to cause a little “short-term pain for long-term gain,” according to Edward Glossop, market analyst with Capital Economics, but will lead to more prosperity after 2017.

The question is whether Argentines, accustomed for generations to short-term socialist panaceas, will have the patience to wait that long.

Photo: AP Images