Six years ago the Romanian Institute for Marketing and Polling reported that 64% of the people felt that their nation was moving in the right direction, toward free-market democracy. Yet last September another survey showed that 49% of Romanians, almost half, felt that life was better for them under communism.

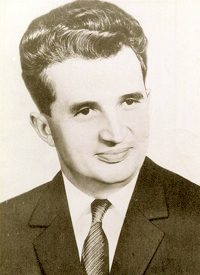

One individual, who lives on an income of $70 a month, expressed her nostalgia for the old days. Elena Bocanu, lighting a candle and placing flowers next to the grave of communist dictator Nicolae Ceau?escu, lamented: “You gave us homes. You gave us gas for heating. Now, we are miserable, like dogs.”

The same change in public sentiment appears in neighboring Bulgaria. Studies conducted by Pew Research Center have shown that while in 1991, shortly after the overthrow of the Communist regime, 76% of Bulgarians felt this change was good — by 2009 and 2010, only 52% of Bulgarians approved of the change to democracy. This frustration with the government was starkly manifested when Bulgarian television engineer Adrian Sobaru, in front of an international audience, leapt 20 feet off a parliament balcony before the assembly in protest of state budget cuts which had resulted in reduced payments for his autistic son. After his release from the hospital, Sobaru asserted, “It hurts that we have become mere numbers.”

Not everyone, however, agrees with this dim assessment of eastern Europe after 1989. Mihai Pop, an ornamental glass vendor in Bucharest, recalls of the Ceausescu era of Romanian history: "It was a prison. In capitalism you are free to do what you want — make money if you want to, don't make money if you don't want to." Certainly the capital of Romania now offers more automobiles, more shopping opportunities, and more evidence of affluence than under the decades of rule by the Ceausescu family.

Like the rest of Europe, Romania is in the throes of an economic downturn. The average monthly income is only €325. In the wake of economic problems, the sales tax rate was increased by 24% and wages in the public sector jobs were lowered. Public subsidies for heating, maternity and disability were reduced as well. Some believe that the nation has never really embraced capitalism. Maricela Popa, manager of a convenience store in Bucharest, declares: "This isn't capitalism; in capitalist countries you have a middle class." She recalls Romania under communism, when employment, housing, and holidays on the Black Sea were subsidized. Simion Berar, a retired mechanic, is blunter: “I regret the demise of communism — not for me, but when I see how much my children and grandchildren struggle. We had safe jobs and decent salaries under communism. We had enough to eat and we had yearly vacations with our children.”

In 1999, a decade after the revolutions of 1989, 61% of Romanians said that their standards of living were higher under communism. Many Romanians do not believe that their nation ever truly had a popular revolution. Instead, they think that the 1989 revolution was captured by Communist Party functionaries and the secret police. Architect Valentina Lupan remembers:

In 1990, I thought there would be real, fair competition — that the best and the most hardworking people would succeed like in the American dream.

When I realized that impostors, the former Securitate and thieves had become the richest people and [were running] Romania, I lost hope — not for me, but for my children.

There is a marked difference between the end of totalitarianism in Nazi Germany and the apparent end of totalitarianism in the Soviet empire (which includes not only the constituent nations of the Soviet Union but also Warsaw Pact nations such as Romania). West Germany went through de-nazification after the war. Nazi leaders were tried at Nuremberg for war crimes and crimes against humanity. There was no similar de-nazification in East Germany. Instead, the communists installed leadership, inviting members of the German military and Nazi security forces to become part of the East German government — and many did.

What was true in East Germany after the war was true in Russia after Boris Yeltsin opposed the Politburo in 1991. There was no punishment for past crimes against humanity in the Soviet Union, or in any of the former Warsaw Pact countries, either. The Soviets had consigned vast numbers of people to slave labor camps in the Gulag, where tens of millions are believed to have died. Like the Nazis, the Soviets also launched aggressive wars, such as the Winter War against Finland and the attack on eastern Poland, which killed millions more. Though these Soviet crimes equaled anything done by the Nazis, the world saw no prosecution or even public remonstrance against the Soviet empire.

The “boss” of Russia today is Vladimir Putin, a former high-ranking member of the KGB. He served first as President of the Russian Republic and is now Prime Minister. Medvedev, nominal President of the Russian Republic, has made it clear that he favors whatever Putin favors. This situation is eerily reminiscent of when Stalin ran the Soviet Union, sometimes without holding any government job at all, yet always wielding vast power. The titles and the portfolios of individuals change in Russia, but not the power structure.

There is another aspect of the decades-long communist rule which affects the states of the former Warsaw Pact, as well as part of the old Soviet Union: Marxists waged a long and savage campaign against religion in general — and the Christian faith in particular. Faith was once an vital part of the life of Eastern Europeans, which enabled them to live happily even despite relative poverty. It was his faith in Christ which allowed Alexander Solzhenitsyn to leave the Gulag determined to oppose the evil of communism. The Polish people, who held to their faith even in the grimmest days of Stalinism, were those most adamant in demanding an end to Soviet rule.

Decades of anti-religious propaganda, the vicious religious persecution of Christian clergy throughout the Soviet realms, and the reintegration of Eastern Europe into a behemoth that has little use for Christianity, has left a deep moral and spiritual void in nations such as Romania and Bulgaria. Liberty cannot long thrive, or even survive, without trust in God — a fact which America’s Founding Fathers well understood.

Romanians and Bulgarians who pine for the "good old days" of communist rule mention the social safety net, the wealth of some compared with others, and similar wholly materialistic values. They fail to comprehend the salient value of religious liberty, because so many of these former subjects of the Soviet empire have come to believe that God is an irrelevancy. Yet without God, life will always be drab, stark, and grim.

Photo: Former Romanian communist dictator Nicolae Ceau?escu