With polls showing 60 percent of the populace opposed to further measures, George Kristos, a political analyst, said that “Papandreou could not take any more political punishment … All parties and all [the] media criticize the government, so Papandreou, in a sense, tried his best to do the referendum to force the parties, the media and the citizens to undertake their own responsibility. The referendum [would be] a yes or no issue: Either you are in favor, or you decide that you say goodbye to the eurozone.”

One of those citizens, Akis Tsirogiannis, a 42-year-old father of two who recently lost his job, said “The government is no longer in control, others are calling the shots.…” He added,

This deal, like all the others, is a life sentence of austerity for Greeks. The country is being run from the outside — by bankers and European Union government [officials]. We need to reclaim our country, whatever that entails.

Tsirogiannis faces formidable odds. Immediately after the PM called for the referendum (which would not be held until after the first of the year), several of his party members publicly criticized the move, and one of them resigned, declaring himself an independent, and cutting Papandreou’s majority in the 300-member parliament to a razor-thin 152. And an opponent, Antonis Samaras, called for a vote of confidence to take place on Friday which could lead to Papandreou’s ouster or resignation.

This prompted the two architects of the eurozone agreement, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Nicolas Sarkozy, to schedule an emergency meeting Wednesday to discuss the matter and present the best face possible to the G-20 meeting which starts in Cannes on Thursday.

One result of the PM’s decision to call for a vote on the new austerity measures could be the replacement of him and his government with another one more amenable to accepting those measures. Instead, however, if new funds from the IMF don’t arrive in time, then Greece will be forced into insolvency. Rainier Bruederle, one of Merkel’s lieutenants, said the PM’s move “sounds to me like someone … trying to wiggle out of what was agreed [upon]. One can do one thing: make the preparations for the eventuality that there is a state insolvency in Greece and if it doesn’t fulfill the agreements, then the point will have been reached where the money is turned off.”

Daniel Ben-Ami witnessed firsthand the impact the present austerity measures are already having on people in Athens: A pensioner is using an old cook stove to keep warm as he can’t afford to turn on the heat; a professional footballer is on strike because his state-funded team can’t pay him; bags of trash are piled high on the streets because the collectors are on strike; and a lawyer working for the government is emigrating because he hasn’t been paid for eight months.

Ben-Ami said, “The government is coming under the control of international agencies. Officials from the ‘troika’ — the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund — are moving into Greek ministries. In effect, the country is becoming a colony of the European Union.”

And the new austerity measures are likely to get much worse. Already the average take-home pay in Greece this year is 14 percent less than last year, and much of the Greek bonds in jeopardy are held by local banks and pension funds. With 50-percent haircuts, those pension funds (and the pensioners relying on them) will see much further reductions in their payouts.

Ben-Ami concluded,

Of course, many would argue that the Greeks are only paying the price for a prolonged credit binge. But it should be remembered that the average Greek is not responsible for the economic chaos that is afflicting his country.

If enough citizens such as Tsirogiannis really are willing to do whatever it takes to “reclaim their country,” it will involve unwinding the EU apparatus that is choking off freedom for him and his countrymen — a job that will be painful indeed.

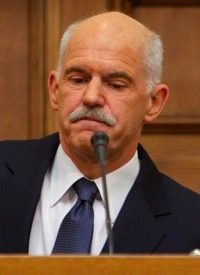

Photo of Prime Minister George Papandreou: AP Images