European leaders reached an agreement over the weekend on bailing out the profligate Greek government with up to $40 billion in taxpayer-funded loans at below-market interest rates, easing fears of a default but prompting outrage among Europeans.

The spend-happy socialist regime used accounting gimmicks and American banks to conceal its massive government debt load from markets and the population. But the cards finally came crashing down as the economic crisis revealed the enormity of Greece’s borrowing problem.

The Euro currency also took a severe beating as investors and currency traders wondered what would come next. Several other European regimes were also teetering on the edge of insolvency, sparking fears of a domino effect if Greece defaulted on its obligations. Some prominent analysts were even forecasting an end to the Euro as a currency. But finally, governments agreed to step up.

“The member states of the Euro zone [group of countries which use the European currency known as the Euro] are going to make available funds via bilateral loans,” announced Eurogroup finance chief and Luxembourg Prime Minister Jean-Claude Juncker at a press conference on April 11. “The Commission is going to coordinate and centralize the funds and the European Central Bank will be the paying agent.”

Public opinion in Germany — the country that will finance most of the aid — and other Eurozone countries is overwhelmingly against putting citizens’ money at risk to bailout Greece. A February poll of Dutch voters revealed that 92 percent favored expelling Greece from the union altogether, and more than 90 percent wanted to abandon the Euro and restore a national currency. But European governments, determined to save their precious “monetary union,” are going forward with the bailout anyway.

The formula for national contributions will be based on policies of the International Monetary Fund and contributions to the European Central Bank. The IMF will also contribute to the bailout and is expected to make available another $20 billion if necessary. In an attempt to deflect criticism, Juncker ludicrously claimed there were no "subsidies" involved. But since the market was demanding more than seven percent interest, loaning taxpayer money at around five percent can hardly be called anything else.

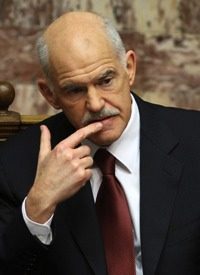

European and Greek government bigwigs emphasized that the loan “mechanism” had not been activated yet, and that it may not even be necessary. But most analysts suspect it be a matter of weeks before the regime in Greece taps the fund. However, just the fact of the money being available is expected to drive down market rates, allowing the government to borrow money less expensively. "No one, any longer, can play with our common currency, no one can play with our common fate," boasted socialist Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou, attacking “speculators” who he tried to scapegoat for the nation’s borrowing woes. After the aid package was announced, the Euro rose against the U.S. Dollar and other currencies.

But some analysts are already warning of potential problems with the bailout strategy down the road. "Europe’s willingness to want to save everyone from everything raises new risks," Société Générale economist Ciaran O’Hagan told Time magazine. He warned that the loans would create a moral hazard by giving governments less incentive to act responsibly knowing that they would be bailed out.

It also doesn’t solve the bigger problems. “It’s a short-term fix and it doesn’t address the long-term problems of Greece or Europe,” chief investment strategist Bruce A. Bittles, with Robert W. Baird & Company told the New York Times. “All of these countries that are strapped with debt, including the U.S., don’t want to face the reality or pain of trying to fundamentally fix the problem.”

And in addition, there is still no such thing as a free lunch. The bailout announcement included a mention of "conditions" that will be imposed on the Greek government if it chooses to accept the offer. Details still remain murky, but analysts suspect the conditions could include more forced tax hikes.

Greece has already approved several “austerity” measures, such as cutting government workers’ salaries and raising taxes in a vain attempt to bring its budget under control. But on top of national policy changes, one recurrent theme throughout the whole crisis has been the imposition of “economic governance” at the European level. “We commit to promote a strong coordination of economic policies in Europe. We consider that the European Council must improve the economic governance of the European Union and we propose to increase its role in economic coordination and the definition of the European Union growth strategy,” announced the Euro Area heads of state and government in a statement released on March 25. “The current situation demonstrates the need to strengthen and complement the existing framework to ensure fiscal sustainability in the euro zone and enhance its capacity to act in times of crises.”

The IMF has also jumped into the fray to support deeper economic “integration” in Europe. And it almost always loans money to its victims with strings attached. "The launching of the euro was only a first step,” explained IMF managing director Dominique Strauss Kahn over the weekend. “You can’t have a single currency without having a more coordinated economic policy." And indeed, more European-level power at the expense of national governments is one of the likely outcomes of the Greek crisis.

Instead of taking the fiasco as an opportunity to implement real reform — less “union,” more freedom and sovereignty, and an end to the “banksters” monetary trap — EU chieftains are taking advantage of the situation to accelerate their “integration” agenda. The people of Europe should instead demand an end to debt-based fiat currency and supranational control of their governments, while obviously forcing their own governments to quit spending so much. But if Europeans don’t step up en masse — and soon — what they will get is the opposite: more debt slavery, increased economic woes, and a continued loss of what little national sovereignty still remains.

Photo of Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou: AP Images