A November 13 press release issued by the UNODC — the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime — stated that opium poppy cultivation in Afghanistan rose 36 percent in 2013, which is a record high. Additionally, opium production amounted to 5,500 tons, up by 49 percent since 2012.

The release cited as its source the 2013 Afghanistan Opium Survey released the same day in Kabul by the Ministry of Counter Narcotics and the UNODC.

Yury Fedotov, executive director of the UNODC, called the news “sobering” and emphasized that the increase in opium production presents a threat to health, stability, and development in Afghanistan and elsewhere. “What is needed is an integrated, comprehensive response to the drug problem. Counter-narcotics efforts must be an integral part of the security, development and institution-building agenda,” said Fedotov.

The report indicated that the area of opium poppies under cultivation in Afghanistan rose to 209,000 hectares from the previous year’s total of 154,000 hectares, and was higher than the peak of 193,000 hectares reached in 2007. (A hectare is equal to 100 acres.)

“As we approach 2014 and the withdrawal of international forces from the country, the results of the Afghanistan Opium Survey 2013 should be taken for what they are — a warning, and an urgent call to action,” Fedotov continued.

When an AP reporter interviewed an Afghan farmer named Khan Bacha, who lives in the village Cham Kalai, in the eastern province of Nangarhar, he provided his explanation for turning to farming poppies. “People are poor, families are big. Wheat is no good,” said Bacha. “The only thing that is good is poppies. They are gold.”

The report noted that there was a five-fold increase in the number of acres planted in poppies in Nangarhar from 2012-2013, representing the biggest increase in Afghanistan.

Nangarhar is a stronghold for Taliban insurgents, noted Kathy Gannon, AP’s special regional correspondent for Afghanistan and Pakistan. She observed that the mere mention of security in the area made Bacha smile. The farmer gestured off in the distance and said that just the night before the Taliban fought a fierce battle with Afghan troops backed by “foreign soldiers” — referring to NATO troops.

Gannon reported that shortly after the AP arrived in Cham Kalai, earlier in the week, the village children began whispering: “Taliban, Taliban.” They knew that the fighters were nearby.

Bacha became concerned for the safety of the AP reporters and warned them: “Go. Go. Now.”

A New York Times report reflected concerns that the increase in opium production in Afghanistan will have a severe impact on the nation after the United States ends combat operations there by the end of 2014.

“We have failed, we have lost — that’s all there is to it,” the Times quoted one Western diplomat, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, stating that he did not want to offend Afghan government officials.

The Times also quoted Jean-Luc Lemahieu, the departing leader of the Afghanistan office of UNODC, who said: “This has never been witnessed before in the history of Afghanistan.”

Despite the increase noted in the UNODC report, Maj. Gen. Khalilullah Bakhtiyar, head of operations for the Afghan government’s Counter Narcotics Police, still maintains that his operation is effective. “Last year alone we confiscated 14 percent of the narcotics produced in Afghanistan and arrested 4,000 smugglers, including small, midrange and major smugglers,” said Bakhtiyar.

The Times report noted that the Taliban militants have opposed poppy eradication efforts in order to gain support among farmers in rural areas, particularly in the southern provinces of Kandahar and Helmand. The Taliban also impose a 10-percent tax on opium production in areas under their control, which provides a major means of financing their insurgent activities.

The British Guardian newspaper also quoted UNODC’s outgoing leader, Lemahieu, who said, “This is the third consecutive year of increasing cultivation,” observing that “the assumption is that the illicit economy is to gain in importance in the future.”

Lemahieu said that those in the international community who were looking for a quick fix needed to think more long-term, stating: “As long as we think we can have short-term, fast solutions to the counter-narcotics problem, we are doomed to continue to fail. That means first knowing this will take 10-15 years.”

While both the Afghan government and Islamic religious leaders denounce the drug trade, local farmers asserts that both authorities claim a share of the profits in the form of taxation.

“We doubt that it is forbidden, because if it is, why are the mullahs taking these taxes?” the Guardian quoted Abdul Khaliq, a farmer who has been growing opium poppies in Helmand province for over a decade to support a family of nearly two dozen people. “We are a lot of people, this is the reason we grow opium. If we do other work, we can’t feed our family.”

Russia’s RT news, which noted that UNODC’s Yury Fedotov is a Russian national, quoted a statement made by Fedotov that predicted a dismal outlook for the war against drug production in Afghanistan: “We have a serious risk that without international support, without more meaningful assistance, this country may continue to evolve into a full-fledged narco-state.”

RT reported that the U.S.-led coalition has forbidden its soldiers to engage in crop eradication operations for fear of bankrupting farmers and forcing them to join the insurgency. This policy, observed RT, has been criticized by Russia, among others.

There have been assertions made that the involvement of the CIA in training the Islamic resistance (Mujahedeen) to the Soviets during the years of Soviet occupation of Afghanistan contributed to the rise of opium production in the country.

A 2008 Global Research report headlined “Pakistan and the ‘Global War on Terrorism’ ” by University of Ottawa Professor Michel Choussudovsky, stated, in part:

Acting on behalf of the CIA, the ISI [Pakistan’s military intelligence, the Inter-Services Intelligence] was also involved in the recruitment and training of the Mujahideen. In the ten year period from 1982 to 1992, some 35,000 Muslims from 43 Islamic countries were recruited to fight in the Afghan jihad. The madrassas in Pakistan, financed by Saudi charities, were also set up with US support with a view to “inculcating Islamic values”. “The camps became virtual universities for future Islamic radicalism,” (Ahmed Rashid, The Taliban). Guerilla training under CIA-ISI auspices included targeted assassinations and car bomb attacks.

Weapons’ shipments “were sent by the Pakistani army and the ISI to rebel camps in the North West Frontier Province near the Afghanistan border. The governor of the province is Lieutenant General Fazle Haq, who [according to Alfred McCoy] allowed “hundreds of heroin refineries to set up in his province.” Beginning around 1982, Pakistani army trucks carrying CIA weapons from Karachi often pick up heroin in Haq’s province and return loaded with heroin. They are protected from police search by ISI papers. (1982-1989: US Turns Blind Eye to BCCI and Pakistani Government Involvement in Heroin Trade See also McCoy, 2003, p. 477)

The report is worth reading in its entirety for its insight into the role of the CIA in recruiting America’s eventual public enemy number one, Osama bin Laden. The report affirms the suspicions voiced by many non-interventionists that our government’s twin wars on drugs and terror are likely just damage-control exercises to undo the havoc brought about by our own covert (and constitutionally questionable) activities.

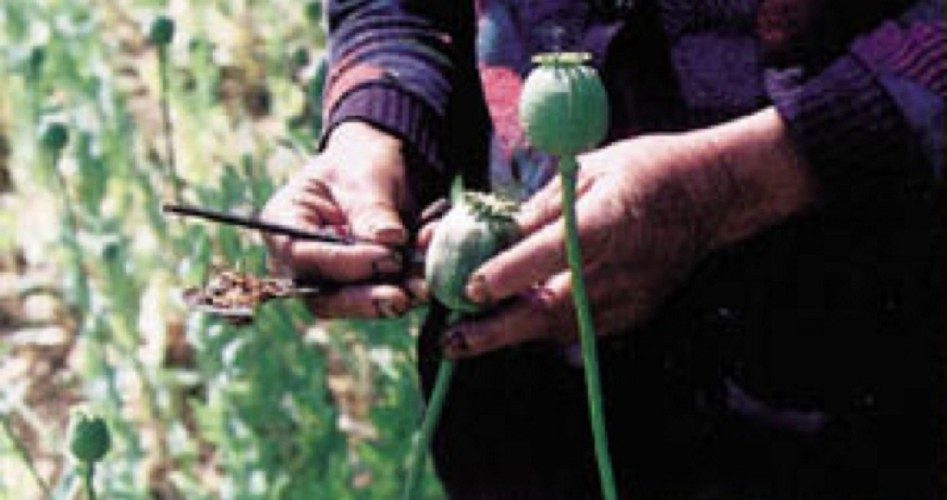

Photo of opium being harvested from poppies: CIA