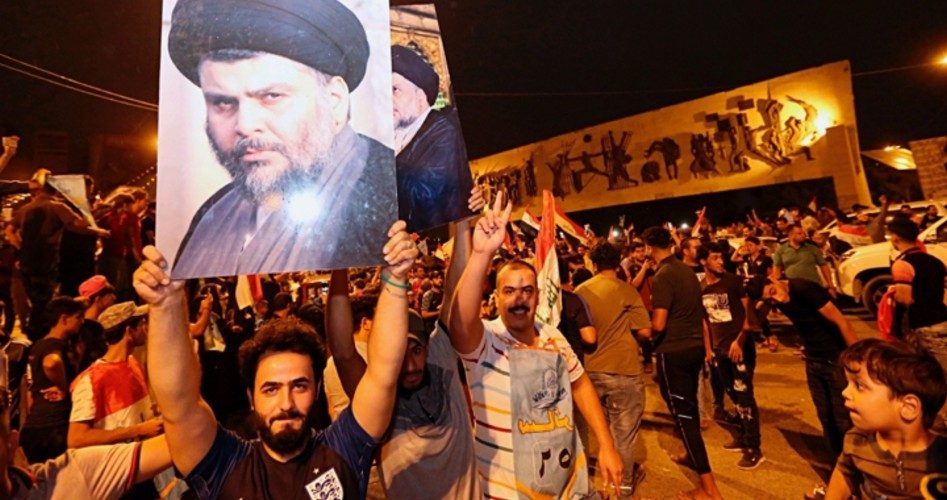

A decade and a half after President George W. Bush declared “Mission Accomplished” in the U.S. invasion of Iraq, Muqtada al-Sadr — the anti-American Shi’ite cleric who led his followers in attacks on U.S. troops in Iraq — appears to be the clear winner in the country’s fourth parliamentary election since the overthrow of Saddam Hussein.

As of this writing, all of the votes have yet to be counted, but the results appear overwhelmingly in favor of Sadr. His almost-certain electoral victory is due to his populist appeal: He advocates expelling all outsiders (especially Americans) and creating an Iraqi government that is made up of Iraqis looking out for Iraq. In a nutshell, Sadr promises to Make Iraq Great Again.

Sadr’s success in riding the populist “Iraq First” wave is due, in large part, to his 2015 alliance with the Iraqi Communist Party and other secular groups “under an umbrella of security and corruption concerns.” The secular/Communist coalition has used Iraqi discontent toward the current government — created in the wake of U.S. occupation — to stoke the fires of anti-American sentiment. The underlying “security and corruption concerns” stemming from the current government — which is seen by many Iraqis as a puppet regime with the strings leading to Washington — played a major role Sadr’s campaign.

Sadr’s criticism of the United States as an evil force in the lives of Iraqis is nothing new. Almost as soon as Hussein and his Ba’ath regime were overthrown, Sadr opposed the Provisional Government established by the Coalition led by the United States, saying he was the legitimate leader of Iraq. He also told 60 Minutes, “Saddam was the little serpent, but America is the big serpent.”

The United States was instrumental in establishing Hussein and his regime in the 1970’s. He was seen by many Iraqis as an American puppet. In the ensuing years, he was seen as a tyrant who treated his people brutally. After he fell out of favor with the United States in the 1990’s, his tyranny only increased. Iraqis blamed the United States for Hussein’s iron reign. The U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 — and subsequent imposition of a Provisional Government — did little to change Iraqi opinion of the United States. So, when Sadr referred to America as “the big serpent” in comparison to Hussein, who was “the little serpent,” he was voicing what many Iraqis felt.

Following those statements, Sadr issued a fatwa which allowed looting by his followers. The fatwa allowed looters to “hold on to what they had appropriated so long as they made a donation (khums) of one-fifth of its value to their local Sadrist office.” This move had the effect of endearing his followers to him while enriching both the followers and the emerging resistance to U.S. control.

Following the success of the fatwa, in late March 2004, Sadr demanded the immediate withdrawal of all Coalition forces, with the threat of violence if the demands were not met. When Coalition forces shut down Sadr’s newspaper for inciting violence, Sadr’s militia attacked Coalition soldiers — including Americans — killing dozens.

Following those attacks, the U.S. administrator in Iraq, Paul Bremer, declared Sadr a criminal.

Sadr responded the following week by having his militia destroy bridges, closing all northbound traffic into Baghdad. The following day — Good Friday — they conducted the largest and most successful convoy ambush of the war, attacking all convoys trying to get to Baghdad International Airport.

Following the Good Friday ambushes, on April 11 — Easter Sunday — Sadr’s militia attacked the Airport and then ambushed trucks as they left.

Given the sentiments of many Iraqis that “Operation Iraqi Freedom” was a smokescreen to invade Iraq and try again to establish a puppet regime in the interests of the United States, the American blood on Sadr’s hands is seen as an endorsement, not an indictment.

Nearly 5,500 U.S. soldiers died in the Iraq War and another 32,000 were injured. To put that in perspective, more Americans died as a result of this one chapter of the War on Terror than died in the 9/11 attacks that were used to provide the rationale for the war — even though Hussein had nothing to do with the attacks. And in the end, Iraq is in possibly worse shape than before the war. The question demands to be asked, “Why were we there?”

This writer is not alone in asking that question. Military journalist Tom Ricks asked it as well, in an article published online. He wrote:

When I saw that the movement led by radical Shiite cleric Muqtada al-Sadr was the big winner in Iraq’s recent elections, my heart kind of sank. I don’t really care one way or the other about him, but I thought of all the American troops who fought and saw comrades die trying to corral him back in the spring of 2004, and I wondered what they thought.

His article includes statements from many veterans of the Iraq War, and they are not very affirming of the “Mission Accomplished” pablum — neither are they the stuff that another war in Iraq is made of.

Bill Edmonds, who served in the Army Special Forces in Iraq and wrote about it in his book God Is Not Here, said, “It’s like all of the pain and loss were for nothing,” adding that Sadr “killed Americans; his rise is a betrayal.” Retired Army Major General Tony Taguba, who served for 10 months as deputy commanding general for support of the Third United States Army, U.S. Army Forces Central Command, Coalition Forces Land Component Command during the Iraq War and who also was assigned in 2004 to report on prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, perhaps summed it up best, saying, “This was inevitable.”

Fifteen years later, it appears Taguba is correct. It also appears that the United States would do well to learn a lesson from this before we repeat it.

Photo of Muqtada al-Sadr supporters celebrating at a rally: AP Images