Anja Niedringhaus, a German photojournalist working for the Associated Press, was shot and killed on April 4 by an Afghan policeman. Her colleague, Kathy Gannon, a Canadian AP reporter, was shot twice and was in stable condition after undergoing surgery at a hospital in Khost. She was afterward transferred to a medical center at Bagram Airfield, north of Kabul and U.S. officials said the military is attempting to evacuate her.

The journalists were traveling with election workers in eastern Khost province in a convoy that was protected by Afghan soldiers and police officers, the AP reported.

“Anja and Kathy together have spent years in Afghanistan covering the conflict and the people there. Anja was a vibrant, dynamic journalist well loved for her insightful photographs, her warm heart and joy for life. We are heartbroken at her loss,” AP Executive Editor Kathleen Carroll said in a statement.

Afghan President Hamid Karzai expressed his sadness over the death of Niedringhaus and the wounding of Gannon.

“These two AP journalists had gone to Khost province to prepare reports about the presidential and provincial council elections,” a statement from Karzai’s office quoted the president as saying. The statement added that Karzai has instructed the interior minister and the Khost governor to assist the AP in every way possible.

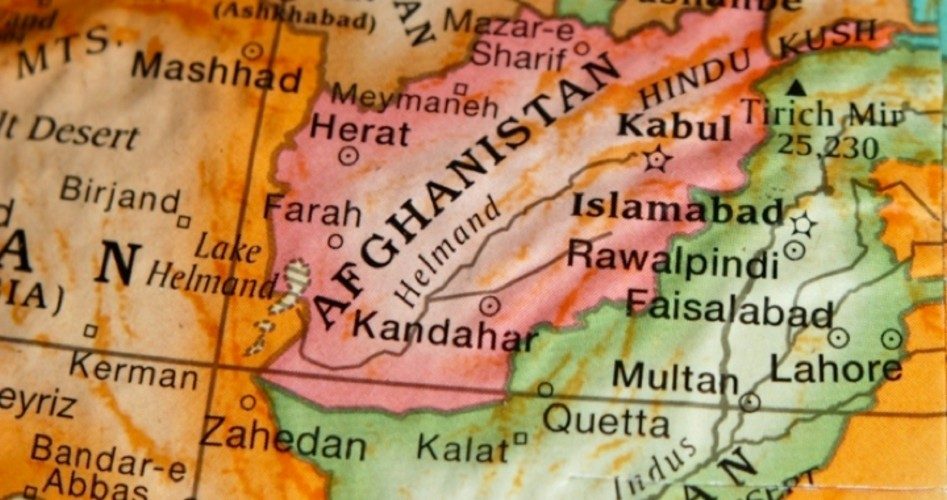

Niedringhaus was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Photography in 2005, as part of a team of 11 AP photographers covering the Iraq War. Gannon was AP’s Afghanistan bureau chief for many years and is currently is a special correspondent for the region, based in Islamabad, Pakistan. She is a former Edward R. Murrow Fellow at the New York-based Council on Foreign Relations and the author of a book, I Is for Infidel: From Holy War to Holy Terror: 18 Years Inside Afghanistan.

Canada’s CBC News interviewed Gannon’s husband, Naeem Pasha, from his home in Islamabad and he told the network: “Kathy has been working in this area for almost 25 years now. It’s like she knows everybody in Afghanistan, and if you asked her, she could rattle off names from one end of the country to the other.”

Pasha told CBC that Gannon and Niedringhaus had been working together in Afghanistan and Pakistan for nearly five years, including several embeds with the Afghan National Army and Pakistani security forces.

CBC reported that Niedringhaus had traveled to Afghanistan numerous times since the 2001 U.S.-led invasion, and had received numerous awards for her photojournalism.

Niedringhaus and Gannon were traveling in a car accompanied by a freelance journalist and a driver as part of a convoy of election workers delivering ballots from Khost to the Tani district in the southern part of Khost province. The convoy was guarded by the Afghan army and Afghan police.

According to Pasha, his wife and Niedringhaus had gone to shoot footage of the ballots for planned pieces on the upcoming presidential and provincial elections to be held April 5. When it started to rain heavily, they decided to wait in their car to protect the camera equipment.

As they sat in the car waiting for the convoy to move, a police unit commander named Naqibullah approached them, yelled “Allahu Akbar”(“God is great”), and opened fire on them with his Kalashnikov AK-47. Naqibullah then surrendered to other police and was arrested.

Though the reason for the attack on the journalists is unclear, CNN cited a statement made to the network by Baryalay Rawan, a spokesman for the Khost provincial governor, who confirmed that police had arrested the suspected shooter and that the case is under investigation.

The Taliban have vowed to disrupt the elections and punish anyone involved in them, CNN noted, and a series of attacks in Kabul and elsewhere have created a tense atmosphere prior to the elections.

In an April 2 attack claimed by the Taliban, a suicide bomber blew himself up at the entrance gate to the Interior Ministry in Kabul, killing six Afghan police officers, said Interior Ministry spokesman Sediq Sediqqi.

CNN also cited a statement from Sakhidad Haidari, the deputy police chief of Sar-e-Pul province, who said that on April 1 a provincial council candidate and nine of his supporters were killed by the Taliban the region.

The resilience of journalists covering the news in Afghanistan in spite of the dangers was emphasized in a piece published online in February by the Committee to Protect Journalists. The article noted:

Local journalists in Afghanistan face mounting threats in 2014 as the country braces for a withdrawal of foreign troops, rapidly diminishing international aid, and a contentious presidential election. Yet many local reporters are upbeat, their optimism reflecting a sense of determination to build on the progress that has been achieved.

A report in the Washington Post also noted the precarious situation of journalists covering the news in Afghanistan, particularly as national elections approach. The Post provided as examples the attack on Swedish journalist Nils Horner, who was shot and killed last month while conducting interviews in Kabul. Additionally, Sardar Ahmad, a reporter for Agence France-Presse, was killed on March 20 with his wife and two children in an attack on Kabul’s Serena Hotel.

Being a journalist covering a war zone — which Afghanistan seems perpetually doomed to remain — has always been a dangerous occupation. Back in 1986, this writer wrote an article for The New American titled “Bleeding Afghanistan.” As part of that coverage, I interviewed a young female freelance journalist who had become involved with the National Islamic Front of Afghanistan in Washington, D.C., and had agreed to accompany Islamic Front members into Afghanistan to record their story for the outside world. At that time, Afghanistan was still under Soviet occupation and would remain so until 1989.

The journalist told us that her journey began in Peshawar, Pakistan, which was then the main base of operations for the many Afghan Mujahideen — which generally means Muslim fighters engaged in a jihad, a holy war, or struggle — but at the time more specifically referred to the rebel resistance against the Soviet occupiers. When the group of Mujahideen escorting the journalist to Afghanistan was ready to depart, she was instructed on the use of an AK-47, one indication that this mission would not be a casual walk in the park!

The party crossed the mountains into Afghanistan’s Paktia province and eventually traveled to within artillery range of the Soviet garrison near Khost — the scene of the latest attack against two other female journalists.

There is much irony in what has transpired in Afghanistan since the days when our government covertly helped the Afghan Mujahideen against the communist Soviet occupiers. Perhaps the greatest irony of all is that one of the most prominent organizers and financiers of the Mujahideen was a man from a wealthy Saudi family who would later become one of America’s most hated villains — Osama bin Laden.

The Mujahideen resistance inflicted heavy casualties on the Soviets and made the war very costly for them, and in 1989 the Soviet Union withdrew its forces from Afghanistan.

One would think that this apparent victory for the Mujahideen “freedom fighters” would have signaled a future of peace and freedom in Afghanistan, but the country has since gone from one bad government to another. Under Taliban rule, the country became a safe haven for bin Laden’s al-Qaeda, which was blamed for the 9/11 attacks, provoking the U.S. war that replaced the Taliban with a supposedly pro-Western government. U.S. troops have stayed there ever since 2001, propping up governments too weak to suppress the insurgents linked to the Taliban and al-Qaeda.

After more than 13 years of U.S. troops in Afghanistan, with a death toll of more than 2,169 troops killed (according to a February AP count), and with 19,639 U.S. service members having been wounded in hostile action, that beleaguered nation is still a land of turmoil, where — as we have just seen — journalists attempting to provide news coverage put their lives at risk.

As journalist Bob Dreyfus noted in a March 31 article for The Nation magazine:

Having a presidential election in Afghanistan is sort of like trying to put Humpty Dumpty together again — that is, if every piece of the eggshell were trying to kill all the other pieces. Thirteen years after the US invasion in 2001, Afghanistan is no closer to being a unified country than it was back then, after a decade of war during the Soviet period, the civil war that followed and finally the conquest by the Taliban.

The U.S. mission officially ends at the end of this year, but our military has requested that as many as 10,000 troops stay on to assist a government incapable of running it own country or providing security for its citizens.

As the British learned after three Anglo-Afghan wars (1839–42, 1878–80, and 1919) and as the Soviets learned during their military occupation of Afghanistan from 1979-1989, Afghanistan is a place where foreign military forces tend to get bogged down interminably, and after a horrific expenditure of blood and money, the land returns to a state of chaos best avoided by sensible outsiders.

The end of 2014 will prove whether Americans have learned from history, or will be condemned to repeat it.