“Leigh Corman knowingly, willingly and voluntarily made statements to the Washington Post regarding her alleged sexual abuse by Mr. Moore that she knew to be false,” reads the 23-page defamation lawsuit filed last week by former Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Roy Moore (shown) against Leigh Corfman, a woman from Gadsden, Alabama. Corfman was quoted by the Washington Post during the time of last year’s U.S. Senate race, in which Moore lost to Democrat candidate Doug Jones, as saying Moore engaged in sexual contact with her 38 years ago, when she was 14 and he was 32.

“Leigh Corman knowingly, willingly and maliciously made statements she knew to be false to the Washington Post with the intention and knowledge that such statements would damage the reputation of Mr. Moore,” the lawsuit charges.

Because of Corfman’s charges, which Moore denies, “irrevocable damage” was caused to his reputation and the accusations “affected outcome of the Senate election in December 2017.”

Corfman had previously sued Moore and his associates for defamation, arguing that they accused of her lying and concocting her story for money or for political reasons.

Neil Roman, Corfman’s lawyer, explained, “Our client has been repeatedly called a liar — including in this court filing by Roy Moore. [One cannot be held liable in a civil action for what is said in a court filing, however.] As we have said all along, Ms. Corfman’s focus is on holding those who say she lied accountable, and we look forward to the discovery process in our case against Mr. Moore and his campaign committee and defending our client in court.”

Moore, through his lawyer, said he was willing to be deposed because he has “nothing to hide.”

Corfman wants Moore to retract his statements against her, and pay her court costs, while Moore desires the court to declare that she “intentionally, negligently, willfully, wantonly and maliciously defamed” him. In addition, Moore is asking for Corfman to “pay for all damages suffered by Mr. Moore as well as to pay the reasonable expenses and costs associated with defending against her allegations and the reasonable expenses and costs associated with his claims against her.”

It will be difficult for either Moore or Corfman to win their suits, under the way courts now view such defamation actions. The New York v. Sullivan Supreme Court decision of 1964 has made defamation lawsuits by “public figures” very difficult to win. In this particular case, Moore is clearly a “public figure,” having served as chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court, and being a candidate for the U.S. Senate. Cofrman, on the other hand, made herself a public figure by voluntarily making her sensational charges through a nationally known newspaper, the Washington Post.

In a defamation case (termed slander for spoken falsehoods and libel for written falsehoods), it is the person who is charging they have been defamed who must prove that the allegedly defamatory statements are false. In a particularly high bar, the plaintiff must additionally prove that the person making the defamatory remarks knew the remarks were false when they made them, or had a “reckless disregard for the truth.”

Intentionality to harm someone’s reputation (malice) is also very difficult to prove. Finally, the plaintiff, in order to collect any damages, must prove actual damage has occurred. In this case, Corfman’s ability to prove damage would be more problematic than Moore’s ability. After all, Moore can point to his loss as a Republican in a deeply-red state of Alabama, and charge that Corfman’s allegations were largely responsible for that loss. It would be far more difficult to convince a jury of what “damage” has been done to Corfman.

As first reported in the Post, Corfman asserted that Moore, then a 32-year-old assistant district attorney, was asked by Corfman’s mother, Nancy Wells, to watch her daughter while Wells went into a courtroom for a custody hearing, which took place in early 1979. Her parents were divorced, and the hearing concerned custody of Corfman. According to Corfman, Moore asked her for her phone number, which she gave him.

Moore later called her on a phone that Corfman had in her bedroom, Corfman claimed.

“Days later, she says, he picked her up around the corner from her house in Gadsden,” the article states.

Moore then took the girl to his home, put his arm around her, and kissed her, she claims. When Corfman told Moore that she felt nervous about the situation, he took her home, she said.

“Soon after, she says, he called again, and picked her up again at the same spot,” according to the article.

This time, Corman asserted that Moore took her back to his house, touched her body, and guided her hand to his underwear, at which point she said she yanked her hand back. Corfman claims that Moore called her again, but she gave him an excuse not to meet up with him again.

Moore disputed several points of the Corfman account, as reported by the Post. There was a hearing on February 21, 1979, but the Moore campaign retorted, “The Post failed to tell readers that at the February 21, 1979, court case, Wells [Corfman’s mother] voluntarily gave up custody of Corfman to Corfman’s father, Robert R. Corfman. The two had been divorced since 1974. The custody case was amicable and involved a joint petition by both parents.”

Moore argues that the article failed to inform its readers that the court ordered Leigh to move to her father’s house, beginning March 4. “Court documents show the father’s address in Ohatchee, not Gadsden, where her mother lived and where Corfman says the meetings with Moore took place,” Moore’s campaign argued last year.

“This would mean,” the Moore campaign noted, “that from the court hearing on February 21, 1979, until Corfman was ordered to move to her father’s house, Moore would only have had 12 days, including the day of the court hearing, to have repeatedly called Corfman at her mother’s Gadsden house, arrange two meetings, and attempt another.” Moore’s campaign allowed that such a timeline is “theoretically possible,” but contended that it was “unlikely.”

The Moore campaign asserted that there were problems with Corfman’s account, “problems” they no doubt will argue in either court proceeding. Breitbart News reported that Wells, now 71, disputed her daughter’s claim that she spoke to Moore on her bedroom phone, explaining that her daughter did not have a phone in her bedroom.

Another detail the Moore campaign asserted as questionable was the location Corfman gave as where Moore allegedly picked her up. The Post article asserted that Moore picked her up around the corner from her house. The Post said, “She says she talked to Moore on her phone in her bedroom, and they made plans for him to pick her up at Alcott Road and Riley Street, around the corner from her house.”

The problem with that account, the Moore campaign contended, is that particular intersection was “almost a mile away from her mother’s house at the time and would have been across a major thoroughfare.”

And since she was now in her father’s custody, she would not have been living with her mother in Gadsden anyway, but rather with her father in another town.

What this sets up, of course, is a situation in which Corfman has no witnesses that she ever had any relationship at all with Moore (claiming she had a phone in bedroom, although there was no phone there; meeting Moore away from her mother’s house, a situation in which there are no witnesses). This creates an almost impossible scenario for Corfman to prove in court — that Moore even knew Corfman, as she cannot produce one witness of that, if this story is accurate. On the other hand, Moore’s attorneys can allege inconsistencies in Corfman’s account, and attempt to impeach her veracity. Whether that would be enough to prove that Corfman knowingly lied about Moore, with the intention of damaging his reputation, is anything but certain.

What is certain, however, is that we can expect more and more of these types of allegations in the future. Partly because of the allegations of Leigh Corfman, published by the left-wing Washington Post, Roy Moore was denied an almost-certain victory in the U.S. Senate race in Alabama.

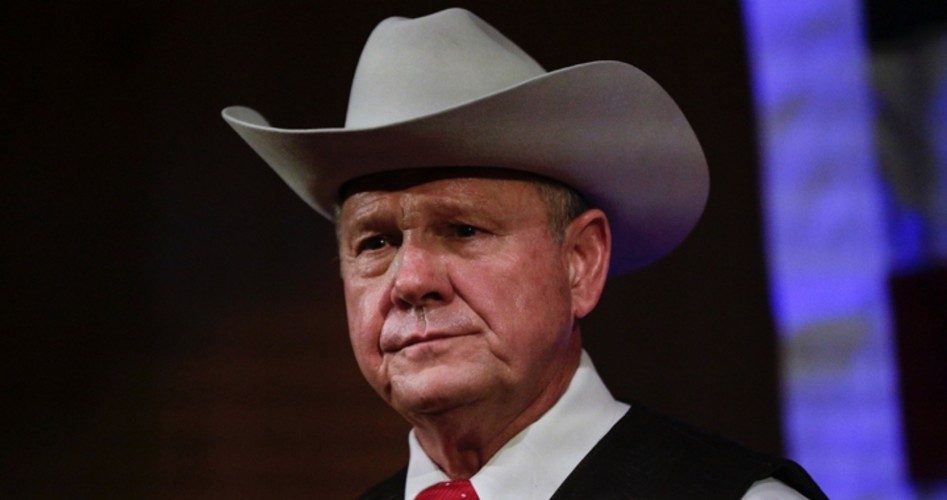

Photo of Roy Moore: AP Images