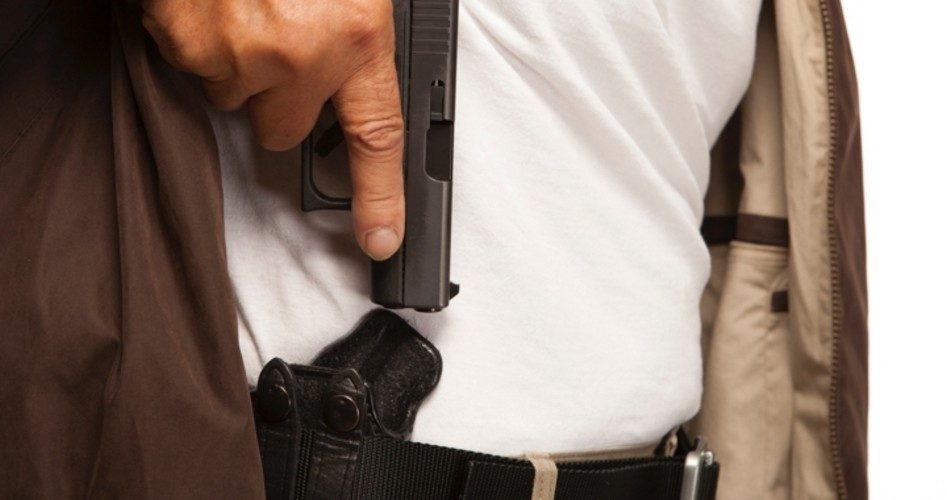

On Tuesday, Kentucky Governor Matt Bevin signed into law Senate Bill 150, making Kentucky the 16th state to allow “constitutional carry.” The law states that “Persons age twenty-one (21) or older, and otherwise able to lawfully possess a firearm, may carry concealed firearms or other concealed deadly weapons without a license in the same locations as persons with valid licenses issued under KRS 237.110.”

Before the 19th century, there were no state laws regulating the carrying of firearms or other weapons by law-abiding residents. Then, states began to restrict the carrying of firearms and require a permit for those who wanted to exercise their right under the Second Amendment to “keep and bear arms,” ignoring the fact that that right “shall not be infringed.” By the 20th century, the only state that did not pass laws infringing the right to keep and bear arms was Vermont.

The constitutional-carry movement began to gain ground in 2003, when Governor Frank Murkowski of Alaska signed House Bill 102 into law. That law marked the first time a state rescinded its laws requiring a permit to carry a concealed weapon. No other state followed suit until 2010, when Arizona passed Senate Bill 1108.

The trend began to catch on, slowly at first, then picking up the pace more recently, with Wyoming (2011), Kansas (2015), Maine (2015), Mississippi (2016), Idaho (2016), Missouri (2016), West Virginia (2016), New Hampshire (2017), North Dakota (2017), Arkansas (2018), Oklahoma (2019), South Dakota (2019), and now Kentucky passing constitutional carry in one form or another.

Many of those states have kept concealed-carry permits on the menu to allow residents who wish to do so to take advantage of reciprocal agreements with other states, allowing them to carry concealed weapons when they travel to those states.

The path to constitutional carry has not been an easy journey in every case. For instance, in Mississippi, the implementation was incremental. The initial law passed in 2013 allowed for “a loaded or unloaded pistol or revolver carried in a purse, handbag, satchel, other similar bag or briefcase or fully enclosed case.” That was expanded in 2016 to include holsters (whether worn on the belt or shoulder) and sheathes.

The passage of constitutional carry in Arkansas could best be described as evolutionary. In August 2013, Arkansas enacted Act 746, making two important changes to the existing law, which previously prohibited “carrying a weapon … with a purpose to employ the handgun, knife, or club as a weapon against a person” and allowed an exception if the person carrying the weapon was “on a journey.”

Those changes were (1) the term “journey” — which had had previously not been defined — was at long last defined as “travel beyond the county in which a person lives” and (2) the addition of the phrase “attempt to unlawfully” to the existing statute, making it read that the law prohibited “carrying a weapon … with a purpose to attempt to unlawfully employ the handgun, knife, or club as a weapon against a person.”

That seemed to make the law say that unless a person was carrying the weapon for the purpose of carrying out a crime, it was lawful to carry a concealed weapon without a permit. But, as the well-known saying goes, the law is an ass. In July of 2013, Arkansas Attorney General Dustin McDaniel issued an opinion stating that Act 746 did not authorize open carry. To add to the confusion, current Arkansas Attorney General Leslie Rutledge disagreed. Rutledge issued a statement in August 2015 saying that it would be within the law to open carry a weapon under Act 746 as long as there is no intent to unlawfully use the weapon.

The issue was finally settled in an Arkansas Court of Appeals ruling in August 2018, when the court declared that carrying a concealed weapon is not — in and of itself — a crime. That court decision ended the debate, allowing Act 746 to mean that Arkansas allows for constitutional carry.

In 2013, Utah’s legislature passed constitutional carry, only to have it vetoed by Republican Governor Gary Herbert. Though the law had passed with a two-thirds majority in both houses, Herbert’s veto was not overturned, and residents of Utah are not afforded the “privilege” to exercise their right under the Second Amendment to “keep and bear arms” in a concealed manner without first asking the state’s permission.

One element that seems important in the growing trend toward constitutional carry is the landmark 2008 District of Columbia v. Heller Supreme Court case. Though the Heller ruling did leave open the idea that some controls over the right to keep and bear arms could be enacted by state and local governments, the court’s interpretation of the protections guaranteed by the Second Amendment were further explained in light of Heller in the 2010 Supreme Court decision in McDonald v. Chicago. The court ruled that the Second Amendment is “fully incorporated” and the “right to keep and bear arms” is not “watered down,” but “fully applicable.” The court went on to rule that the Second Amendment limits state and local governments from passing laws that restrict the “individual” and “fundamental” right to “keep and bear arms” in “self defense.”

As the trend hopefully continues to grow and more and more states remove the shackles that have bound the hands of the law-abiding, America may see a return to the time before the passage of restrictive anti-gun laws of the 19th and 20th centuries. Perhaps, in our lifetimes, we will see the right to keep and bear arms no longer infringed.