“The compact is an end run around the Constitution. It would lead to litigation,” Hans von Spakovsky, a senior legal fellow at The Heritage Foundation, said in an article published this week at the Daily Signal. Spakovsky warned that the National Popular Vote (NPV) movement, which would essentially gut the Electoral College method of choosing presidents, would result in chaos.

Indeed, can one imagine a future election held without the Electoral College.

Say it is only a few weeks before a new president is to be sworn in, but the election has failed to produce a clear winner, as America has gone to a national popular vote system. The Republican candidate appeared to have edged the Democrat nominee by a mere 4,123 votes nationally, out of more than 135 million cast.

Of course, the Democrats refused to accept the results, and somehow “found” some additional votes in Chicago and Philadelphia to put their candidate in the lead. Just as amazingly, Republicans in several small counties in Oklahoma, Texas, and Nebraska “found” some additional votes, putting the Republican back ahead.

Lawsuits fill the nation’s courts. Riots break out across the country, and National Guardsmen roam the streets, seeking to restore order. A national recount has begun, conducted by the U.S. Election Agency, created by Congress in the wake of the abolition of the Electoral College (since the winner of the presidential election is now determined by the national popular vote, rather than the popular vote in the states, this was considered yet another “necessary” transfer of power from the states to the federal government).

Yet, after three weeks, it has become apparent that the country would never settle — peacefully — who had actually won the election.

Despite this grim scenario that could become reality were America to ever actually abolish, either officially or unofficially, the Electoral College, NPV advocates continue to push for a change in the system of presidential election created by the Founding Fathers.

Fortunately, the movement has hit a snag, as more and more Americans are resisting altering our process of choosing a president. Advocates failed to get enough signatures in Arizona and Maine to place the NPV on their November ballot. But, lest supporters become overconfident, the legislature in Connecticut joined the NPV compact in May, bringing the proposal to within only 98 electoral votes shy of success.

The NPV anti-Electoral College supporters understand that their chances of actually amending the Constitution to abolish the Electoral College officially are practically nil. After all, they would need both houses of Congress, by two-thirds vote, to send an amendment to the states, and three-fourths of the states would have to ratify the proposal. Because they know that is unlikely to happen, the NPV movement argues that states can instead agree with other states to give their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote, regardless of who wins their state popular vote.

This is why Spakovsky called the NPV proposal an “end run” around the Constitution.

As it stands now, the compact has won in only 11 states — all Democratic “blue” states (the District of Columbia also favors the NPV, not surprisingly). The compact would not go into effect until enough states are in place to equal 270 votes — the minimum majority of the Electoral College vote. States that have passed the compact are California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington, plus the District of Columbia.

Clearly, Democrats from larger-population states are the base of the NPV support, and NPV leaders realize they need some Republican-leaning states to get past 270 electoral votes. Accordingly, one of the lobbyists that NPV uses to court Republican legislators is Ray Haynes, a former Republican member of the California Senate.

Haynes told the Daily Signal, “The Electoral College doesn’t protect small states. It’s not learned people discussing who should be president. That’s all horse manure.”

The proposal has won in one of the chambers of some Republican-majority legislative bodies, such as in Arizona and Oklahoma, but ultimately failed in the other chamber. (As an aside, this is one argument in favor of having a two-house legislative body). In 2014, the Oklahoma Senate, heavily Republican, passed the proposal. Many conservatives in the state expressed shock, believing that no Republican legislator would even consider such a proposal. No Democrat has managed to carry even a county in Oklahoma in almost two decades, yet the NPV proposal would have given the state’s electoral votes to Al Gore, Barack Obama, and Hillary Clinton had it been in place. Later, it was discovered that the NPV explained the supposed virtues of the proposal to several Republican legislators — in an all-expenses-paid trip to the Virgin Islands.

Tara Ross, author of The Indispensable Electoral College: How the Founders’ Plan Saves Our Country from Mob Rule, noted that the 2016 election demonstrated to those in the so-called flyover states why they should like the Electoral College.

Fortunately, private citizens who had educated themselves on the dangers of this proposal — and who did not get expense-paid trips to an island paradise to be indoctrinated into the NPV scheme — killed the effort in Arizona.

The Arizona NPV effort failed to get the required 150,642 signatures by the July 5 deadline to get the proposal on the November 2018 ballot. One of those who battled the high-dollar lobbyists of the NPV was Bob Hathorne of Scottsdale, Arizona. He spoke in every Republican legislative district, to Republican women’s clubs, and to other activist groups, using a slideshow to illustrate how the NPV was a dangerous idea.

“Every Republican legislative district played a major role in taking down the insanity of the National Popular Vote Compact,” Hathorne told the Daily Signal. “States are free to enter interstate compacts, providing they do not interfere with the sovereign rights of other states not in the compact. Does this compact deny the right of sovereignty to other states? Yes, it does.”

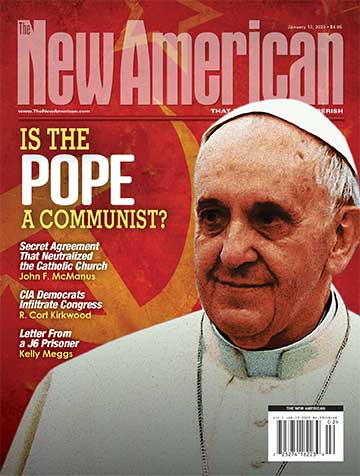

Hathorne’s work to defeat the NPV is highly commendable, and a powerful illustration of the power of informed citizens to make a difference. This is the type of effort encouraged by The John Birch Society (parent organization of The New American) — educating members on important issues and fundamental governmental concepts, and applying that knowledge to specific issues such as the National Popular Vote.

In fact, Birch Society member Barbara Bleuster of Arizona spoke with The New American for this story. Bleuster is a former member of the Arizona House of Representatives from the Prescott area, who recently spoke to an activist group on the problems of the National Popular Vote. She told The New American why the proposal was defeated in Arizona: “I don’t see National Popular Vote as being popular here. Most people can see that it perverts our system, with its checks and balances.”

Hathorne explained that Arizona was a huge defeat for the NPV crowd: “We were the lead red state for their domino effect.”

J. Christian Adams, president of the Public Interest Legal Foundation, contends that the NPV is flatly unconstitutional, citing Article I, Section 10 of the U.S. Constitution, which says, “No State shall, without the consent of Congress … enter into any agreement or compact with another state.”

While such clear language would seem to settle the issue, those who oppose the NPV should realize that the Constitution has been ignored on many other issues. As such, the battle against the NPV needs to continue.