A lawsuit has been filed against Liberty High School in Hillsboro, Oregon, for refusing to allow a student, senior Addison Barnes, to wear a pro-Trump border wall t-shirt to class. And while it is appropriate for schools to set dress codes for their students, the lawsuit notes that the school took action not because Barnes violated any sort of school dress code, but because others were simply “offended” by his shirt.

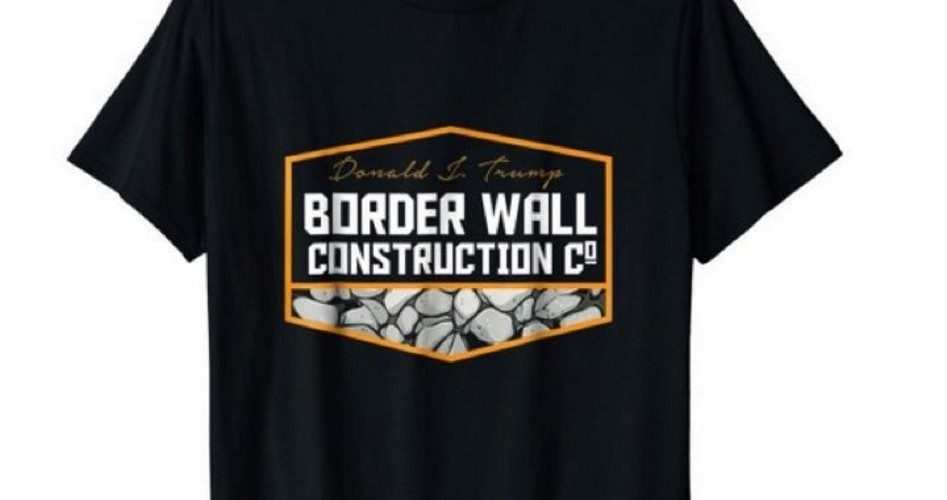

Barnes told Fox 12 Oregon that his shirt read, “Donald J. Trump Border Wall Construction Co.” It also featured a Trump quote: “The wall just got 10 feet taller.” He was asked to cover up the shirt or leave the school. Initially, he opted to cover up the shirt, but decided that he’d prefer to go home rather than have his freedom of speech violated. “I thought to myself, ‘You know this isn’t right, this is my First Amendment right to be able to wear this shirt,’” Barnes said. “So I took off the jacket and the assistant principal had seen that and sent for a security guard to escort me out of class.”

His absence was treated as a suspension, though that was later rescinded, Fox News reports.

Barnes contends that the school has tolerated other political views and that he was targeted because his shirt was pro-Trump. “I had a teacher who had a pro-sanctuary-city poster in her room which was up all year, yet as I wear a pro-border wall shirt, I get silenced and suspended for wearing that,” he told the station.

According to the lawsuit, a teacher and two students took offense to the shirt. Senior Mark Guzman told KGW that the school is very “Latino-populated” and that Barnes’ shirt “offended a lot of people.”

The lawsuit argues that Barnes’ First Amendment rights were violated. It claims, “The First Amendment protects students’ right to speak on political or societal issues — including the right to express what school officials may consider unpopular or controversial opinions, or viewpoints that might make other students uncomfortable.”

The lawsuit continued by stating that Barnes’ shirt did not contain graphics or language that would generally be considered unacceptable. “Barnes’ shirt did not substantially disrupt or materially interfere with the work of the school or the rights of his fellow students,” it reads. “The shirt did not promote or advocate illegal activity; it contained no violent or offensive imagery; nothing on it was obscene, vulgar, or profane.”

However, schools can and should have the right to determine dress codes for their students and staff that should be applied uniformly across the entire population. If, for example, the school dress code asked all students and staff to refrain from donning items that convey a political belief, it would certainly be acceptable so long as it was enforced regardless of the political view being touted.

But the lengthy presence of a pro-sanctuary city poster in a teacher’s classroom seems to disprove any potential claims that the school adheres to a strict policy of prohibiting political views from being conveyed on school grounds.

Furthermore, when Barnes was asked to remove or cover his shirt, it did not cite any specific policy that Barnes may have violated. Instead, the request followed after other students expressed that they were “offended” by the ideas or messages his shirt conveyed.

This sets a dangerous precedent. If offending others is the benchmark for the school’s dress code, where does the line get drawn? What would stop an atheist from saying that he or she was offended because another student was wearing a crucifix around his or her neck, or a shirt that reads, “God is good”?

The school adheres to the Standards of Student Conduct adopted by the Hillsboro School District, which allows students the “general right to freedom of expression within the school system.” This includes clothing, so long as it is not “decorated or marked with illustrations, words, or phrases that are disruptive or potentially disruptive, and/or that promote superiority of one group over another.” Only when clothing or grooming “clearly disrupts learning or presents a health or safety hazard” will a student be asked to change attire.

Of course, this brings up another question. If an article of clothing prompts a disruption, should the student wearing the clothing be held responsible? Or rather, should the students who felt prompted to engage in disruptive behavior, rather than controlling their reactions, be held responsible? That may be a question for another day.

Nevertheless, there is no evidence that Barnes’ shirt was disruptive. Administrators simply claimed that the students and teacher felt “offended” by it.

But is that a legal standard? The lawsuit cites Tinker v. Des Moines Indep. Cmty. Sch. Dist., wherein the Supreme Court observed that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” The court also noted that student speech could not be suppressed on the “mere desire to avoid the discomfort and unpleasantness that always accompany an unpopular viewpoint” or “an urgent wish to avoid the controversy which might result from the expression.”

And yet that seems to be exactly what happened to Barnes. Liberty High School placed the feelings of other students and a teacher over Barnes’ First Amendment rights. Simply put, the Constitution does not guarantee the right to not be offended. The lawsuit asks a judge to uphold Barnes’ First Amendment rights to wear the shirt in the future, as well as nominal damages.