Those concerned about the dangers inherent in a Constitutional Convention won a huge victory when, late last week, the Mississippi Senate allowed House Concurrent Resolution 56 to die, a resolution that would have made an application to Congress for a convention to propose amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

Many conservatives and others frustrated by the failure of the federal government to adhere to the Constitution have pushed for a so-called Convention of the States to consider amendments to the Constitution, ostensibly to rein in an out-of-control federal behemoth. But this is a dangerous game, and the John Birch Society (JBS) in Mississippi alerted its members to those dangers. (The JBS is the parent organization for The New American magazine.)

After its passage in the Mississippi House of Representatives, an “Urgent Action” alert was sent to JBS members asking them to call their senators and give them some of the reasons why calling a national convention to consider constitutional amendments could, as the alert warned, lead to “a potentially disastrous convention.”

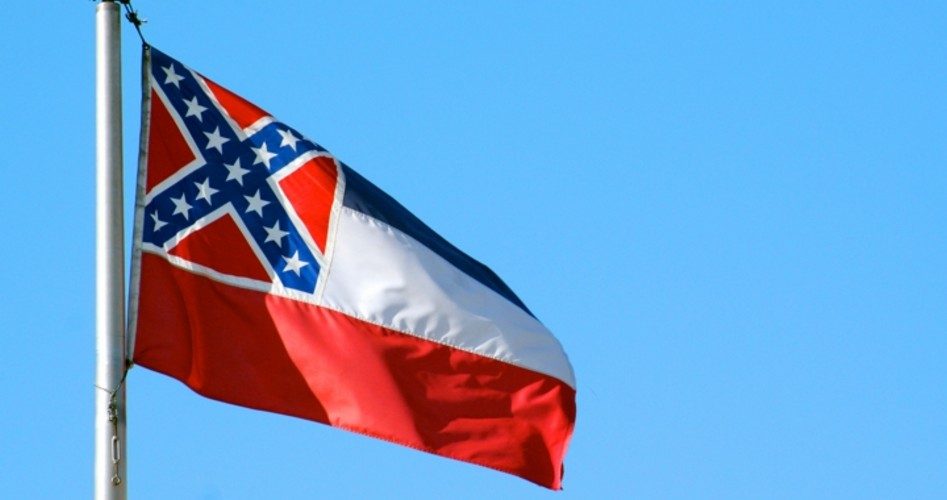

The stunning defeat of the resolution in Mississippi is a powerful demonstration of how an educated citizenry can make a decisive difference, especially when knowledge is combined with concerted action, as was the case with JBS members in the Magnolia State.

With the Mississippi Legislature scheduled to adjourn on April 1, the proposal is almost certainly dead for this session. The Mississippi House had adopted HCR 56 on March 22 by a vote of 76-42. Had the Senate Rules Committee sent the proposal to the full Senate, and had it then been adopted, Mississippi would have become the 13th state with a live Convention of States-type Article V convention application.

The U.S. Constitution, in Article V, provides two ways to propose amendments to the Constitution. All 27 amendments thus far have been sent to the states for ratification via the first method, which is two-thirds vote of both houses of Congress. The second method requires the application of two-thirds of the states (presently 38 of 50) to petition Congress to call a national convention to consider and, perhaps, propose back to the states, amendments.

This second method has never been used in American history — for several good reasons.

Americans as far back as James Madison have expressed concern about the possibility of calling such a convention. More recently, the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia said that this was a not a “good century” for such a convention.

Supporters of the idea of a constitutional convention, or a “Convention of the States” as they prefer to call it, note that the text of HCR 56 states that such a convention should be “limited to the subject matter contemplated by this application.” The “commissioners,” as the resolution calls the delegates to the imagined convention, are instructed that they are “expressly limited to consideration and support of amendments that impose fiscal restraints on the federal government, and amendments that limit the power and jurisdiction of the federal government, and no amendments on any other topic whatsoever.” This text was included, no doubt, to allay the fears of a “runaway convention.”

Regardles of what the text of the resolution says, the concern that such a gathering could become a “runaway convention” is valid. Nothing in Article V of the Constitution provides that such a convention could be limited. The harsh reality is that all Article V conventions have the inherent power to become runaway conventions, because of the inherent right of the sovereign people to “alter or abolish” our government as found in the preamble to the Declaration of Independence. It is even possible that the convention could write an entirely new document, as the original Constitutional Convention did in 1787.

While that document is praiseworthy, the delegates in 1787 were also “limited” to just making amendments to the Articles of Confederation. A convention today is less likely to have such personages as George Washington, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton, and more likely to have delegates like Nancy Pelosi, Paul Ryan, Chuck Schumer, and Mitch McConnell.

With the present campaign to repeal the Second Amendment protections of the right to keep and bear arms, there is no question that such an attempt to eliminate this right would be made at any such convention. It should also be noted that any Article V convention would enable powerful special interests to revise the Constitution in their favor. Not only would limited-government conservatives be at the convention, but we could expect many delegates who favor expanding the scope and power of the federal government to also be present. Who is to say that the Big Government-loving delegates would not be in the majority?

A Convention of the States in this present atmosphere is playing Russian Roulette with the Constitution.

HCR 56 expressed the commendable desire to propose amendments “for the purpose of restraining” abuses of power by the federal government. “Ceasing to live under a proper interpretation of the United States Constitution,” the resolution reads, “the federal government has invaded the legitimate roles of the states through the manipulative process of federal mandates.”

The problem the Con-Con supporters in Mississippi and elsewhere should consider is that if the federal government is not living under a proper interpretation of the Constitution now, what makes them think the federal government would live under a proper interpretation of an amendment passed out of a Convention of the States?

“(A) convention of the states means that the states shall vote on the basis of one state, one vote,” HCR 56 boldly asserts. But that is all it is, an assertion. Perhaps the framers intended for that to be the case, but sadly, Article V does not say anything about how the delegates to such a convention would be chosen. The expression, “Convention of the States” does not even appear in Article V. It is doubtful that the more populous states, such as California, would agree to a convention in which they have no more representation than the small-population states. Who would settle such a dispute? Perhaps Congress, perhaps the Supreme Court. Who knows? It is yet another of the many problems associated with any such Constitutional Convention.

The proposed resolution that the Mississippi Senate killed said it would be in effect “until the Mississippi Legislature acts to withdraw this application.” That is exactly what those states that have passed this dangerous resolution need to do. Others that have not yet passed it need to follow the lead of the Mississippi Senate, and kill it.

In short, the Constitution is not the problem. It is the failure of our elected representatives to follow the Constitution as it is written that is the problem. Turning over to the delegates of such a proposed convention the ability to rewrite our Constitution is not in the interest of any person who believes in limited government.

Image: lorae via iStock / Getty Images Plus