When 1,816 votes disappeared in Hays County, Texas, officials essentially said, “Oh, well.” An electronic voting machine that had been taken offline on election night, November 2016, had been forgotten. Elections Administrator Jennifer Anderson declared it “a process error — we’ve moved on.” Residents blame sloppy election methods and fear that the error will provide justification for more electronic “solutions” for vote-counting problems. What fair-election advocates really want is hand-counted paper ballots.

Since Texas adopted electronic voting, vote-integrity defenders have educated voters about potential problems, including proprietary software issues, inaccurate counts, equipment malfunctions, vote-flipping, and serious state law violations that have surfaced. To activists lobbying for a paper record in voting, this “missing vote” news offers hope, though local officials’ actions have been detrimental to integrity in voting.

In Hays County, the fluke discovery of one miscounted vote on a ballot item set events in motion leading to the discovery of the other uncounted votes, leaving outraged residents clamoring for paper. When the issue, which affected two voters, was discovered, the voters sued the county. After a district court ruled in their favor, an investigation eventually discovered the additional 1,816 votes on the same machine. A citizens committee was then formed to develop citizen oversight of the voting process — especially since the county is considering purchasing new voting equipment — but the county officials wanted nothing to do with advice from local citizens.

Hays County resident Jim Keller said, ”The system’s broken. Big county decisions are being made without public scrutiny.” So committee member Sam Brannon garnered help from interested locals, and decided to attend the public meeting about the purchasing decision. When the locals showed up at the meeting that was set to consider a new electronic vote system, sheriff’s deputies escorted them out of the room, though public oversight is clearly needed in this instance.

The unpopular electronic system of choice in Hays County is manufactured by Hart InterCivic, and it doesn’t meet requirements set out in the Texas Constitution. A serial number on ballots is required by the Texas Constitution, and a new hybrid system manufactured by rival ES&S is the only one available to date that provides such. The hybrid provides a critical unique serial number, which has gained attention in recent months due to efforts of another Texan, Laura Pressley, whose own work uncovered violations of state laws in many Texas counties.

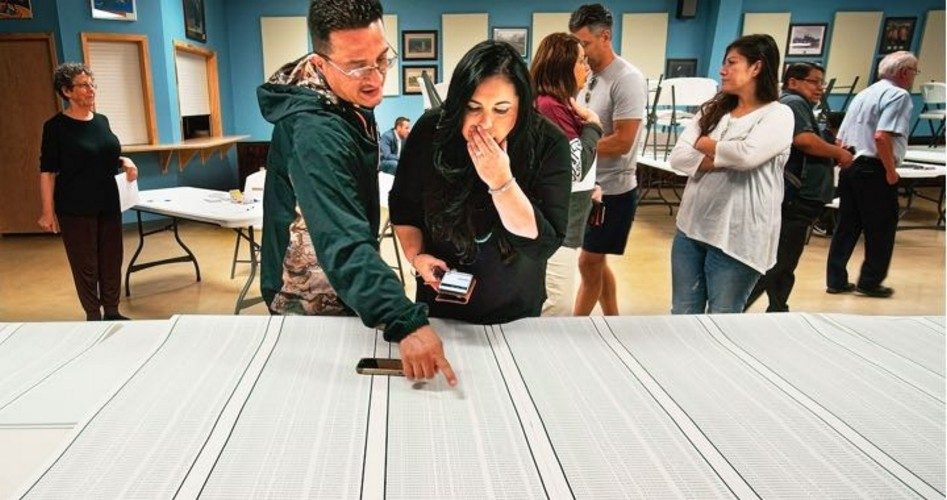

Being escorted from the county meeting sparked locals to hastily arrange a public meeting the following week to present the hybrid system and garner support for more citizen oversight. On June 5, 70 or so citizens attended the public meeting, and many received an unexpected shock when they discovered they were part of the 1,816 voters whose votes were invalidated by the county.

A wall-sized copy of the names of the 1,816 missing votes was available for viewing (though county officials denied being able to provide the list) and many attendees were jolted to find their own names listed. Naomi Narvaiz, state Republican executive committeewoman, said her husband, Jeffrey, discovered his name on the list. “It’s sickening to learn a citizen’s constitutional right has been violated. I’ve worked hard for years to encourage voter participation because a person’s vote is their voice.”

Across the aisle, Fidel Acevedo, LULAC’s District 12 director, noted, “Trust, and accountability in a verifiable system are the two most important things. We don’t have that.”

The situation has worsened for the county in recent days. Jeffrey Narvaiz and two others filed an “intent to sue” notice, requesting the county preserve records for pending litigation. New evidence shows hundreds of additional votes were missing from Hays County’s November canvas.

Jacob Montoya, mayoral candidate and plaintiff in the suit, says the county’s issues damage efforts to increase voter turnout: “Do you think the younger generation is going to vote after something like this? My vote didn’t matter. First of all, they didn’t count it, and then when they did find it, they didn’t count it anyway.” State law prohibits uncounted votes from being added once the vote is canvassed.

Brannon is now looking for a way to formally investigate elections in Hays County: “I want to know how bad this really is, and how long it’s been going on.”

Hays County’s purchasing decision has been stalled due to voters’ persistence in demanding accountability and more oversight. This Texas county is a microcosm of election problems across America, so this case, along with Pressley’s, merits attention.

Photo of citizens perusing the names of the 1,816 disenfranchised Texans in Hays County: Jim Keller