The answer, of course, is politics. Romney, thinking he now has the GOP nomination in the bag, is trying to straddle the political divide, moderating his tone for the general election without alienating the Republican base that must turn out on Election Day if he is to prevail over Obama.

Obama has decided to push the student loan issue as a way to drum up excitement for his candidacy among young voters, most of whom still support him but — perhaps having been disappointed in his administration’s relative continuity with that of George W. Bush — are considerably less eager to show up at the polls to vote for their man than they were four years ago.

The interest rate on Stafford loans is currently 3.4 percent, down from 6.8 percent in 2007, when the Democrat-controlled Congress passed a law gradually reducing rates through this year. The rate, however, is set to return to its 2007 level in July if Congress does not reauthorize the cut.

Obama is asking Congress to do just that, arguing that allowing the rate cut to expire would add nearly $1,000 a year to the debt of each of 7.5 million students. He made a pitch for it in his weekly radio and Internet address and is campaigning for it in person at universities and on NBC’s Late Night with Jimmy Fallon.

House Republicans oppose the idea because keeping student loan interest rates low could cost taxpayers as much as $6 billion a year, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

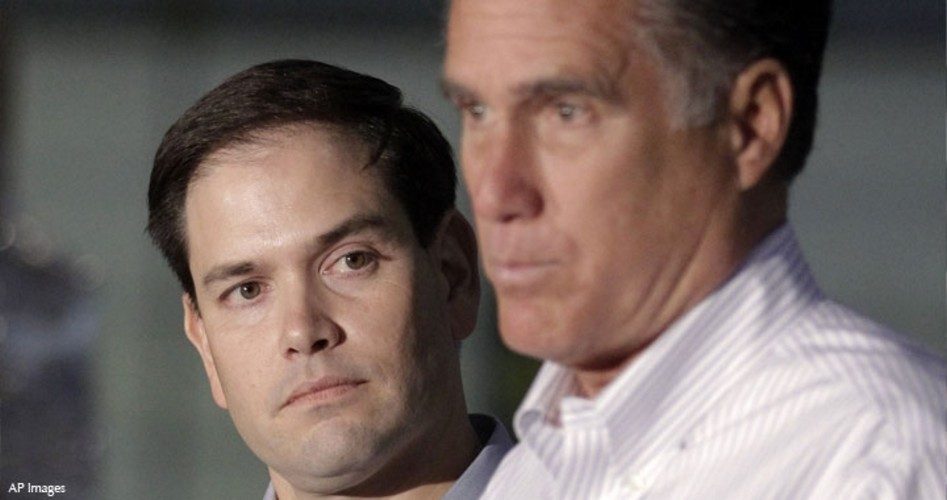

During a Monday campaign stop in Pennsylvania, Romney, accompanied by Rubio, made a particular point of mentioning that he “support[s] extending the temporary relief on interest rates for students … in part because of the extraordinarily poor conditions in the job market.” The remark was clearly aimed at attracting support among young voters, who Romney said earlier in his press conference “have to vote for me if they’re really thinking of what’s in the best interest of the country and what’s in their personal best interest.”

Meanwhile, taxpayers, young or old, must apparently take a back seat to Romney’s electoral hopes.

Rubio is proposing legislation that he calls a Republican version of the DREAM (Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors) Act, a bill that would have put illegal immigrants who had completed two years of college or military service on a path to citizenship. Rubio’s version would give illegals who have met similar criteria non-immigrant visas, allowing them to remain in the country legally but not automatically to become citizens.

Asked Monday whether he supports Rubio’s proposal, Romney “refused to embrace” it, the Associated Press reports, though he did allow that “there were provisions to ‘commend’ it and that his campaign would ‘study the issue.’” He also said he would be offering his own immigration proposals in the months leading up to the election.

Romney’s public coolness toward Rubio’s bill is curious indeed. “Rubio has said his goal is to craft a Republican compromise on the so-called DREAM Act that Romney could support,” the AP writes. If the Senator were chosen as Romney’s running mate — Romney declined to comment on that possibility — it could prove rather awkward for Rubio to be pushing legislation Romney opposes. Moreover, according to a Los Angeles Times op-ed by Tamar Jacoby, last week “Romney told attendees at a closed-door fundraiser that he supports” Rubio’s bill. Why, then, will he not say so publicly?

The bill, along with a veep pick of Rubio, would seem to help Romney pick up support among Hispanic voters, another bloc that went heavily for Obama in 2008. It might also help somewhat with the youth vote since it is aimed at young adults who as children were brought into the country illegally by their parents.

There is, however, that little matter of the Republican base to consider. The original DREAM Act was especially unpopular with conservatives — R. Cort Kirkwood, writing in The New American, declared it “an insane plan” — who viewed it as a thinly disguised amnesty for illegals. The bill passed the House in late 2010 but died in the Senate. How conservatives will respond to Rubio’s proposal remains to be seen, but it wouldn’t do Romney any good to come out in favor of it now only to find out later that the GOP base holds it in almost as much contempt as the DREAM Act itself. Undoubtedly he believes it better to play things close to the vest for the time being, leaving the impression that he is still the hard-line anti-amnesty candidate he claimed to be during the early primary season, when, according to the AP, he said “that all illegal immigrants should return to their home country and get in line to be eligible for U.S. citizenship.” If Rubio’s plan gains traction among conservatives, Romney will probably announce he supports it; otherwise, he — and Rubio — will most likely just let it drop quietly.

In any event, it is clear that Romney’s positions on these — and most other — issues are driven by purely political considerations and, as such, are subject to change without notice. For today the former Massachusetts Governor is in favor of keeping student loan interest rates low and is undecided about the “GOP DREAM Act.” Tune in tomorrow to discover his latest positions on those matters.

Photo: Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), left, with Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney at a news conference prior to a town hall-style meeting in Aston, Pa., April 23, 2012.: AP Images