What exactly is the status of the U.S. military’s official policy on the 17-year-old “don’t ask, don’t tell” law, which allows homosexuals to serve in the armed forces — as long as they don’t tell anybody they’re “gay”? Not even Army Secretary John McHugh seems clear, as demonstrated by a comment he made to reporters in late March. When pressed on the status of the policy, which President Obama is pressuring Congress to overturn, McHugh said he believed Defense Secretary Robert Gates had placed a moratorium on dismissals of homosexuals from the military pending a Pentagon survey of troops on their views of the issue.

But on April 1 McHugh reversed his statement, explaining that he had misspoken and that the policy remains fully in effect. “There is no moratorium of the law and neither [Secretary Gates] nor I would support one,” McHugh said. In other words, soldiers who are found to be practicing homosexuals may still be discharged, even though Mr. Obama has pressured military officials to ease up on enforcing the stricture. The Commander in Chief’s demands have apparently been accepted among top military brass, as Gates recently announced guideline changes that will make it more difficult for someone to present evidence showing that a member of the military is homosexual, and will place the final decision for dismissal in the hands of higher-ranking officers.

Since 1993 an estimated 13,000 military personnel have been discharged under the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy, with the majority being dismissed after identifying themselves as “gay.” Apparently, however, it is even becoming more difficult to be discharged for “outing” oneself, as was demonstrated recently when three soldiers confessed privately to Army Secretary McHugh that they were homosexual. McHugh later admitted he should have handled the situation differently, given the fact that the policy is still the law of the land. “I might better have counseled them that statements about their sexual orientation could not be treated as confidential and could result in their separation [from the Army] under the law,” he said.

Treating the situation as a mea culpa, McHugh said he had decided against pursuing actions against the homosexual soldiers. “Because of the informal and random manner in which these engagements occurred, I am unable to identify these soldiers and I am not in a position to formally pursue the matter,” he said.

Even the Pentagon seems willing to turn a deaf ear to admissions of homosexual behavior from military personnel as it researches the opinions of troops on the issue. Finding themselves in a catch-22 of wanting to hear the opinions of homosexual personnel but being forced to discharge anyone who admits to being homosexual, Defense Department officials have decided to farm out the survey task to a non-military contractor, which will allow homosexual soldiers to share their views with no fear of reprisal.

Meanwhile, except for the cases of the three self-admitted homosexual soldiers, Army Secretary McHugh assured the public that the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy remains in effect for now. “Until Congress repeals ‘don’t ask, don’t tell,’ it remains the law of the land and the Department of the Army and I will fulfill our obligation to uphold it,” he said.

On February 2, barely a week after Mr. Obama challenged Congress to repeal the “don’t ask, don’t tell” law, Defense Secretary Gates announced that the Pentagon had already begun to move forward with plans that would allow homosexuals to serve openly in the military. “The question before us is not whether the military prepares to make this change, but how we best prepare for it,” Gates said. “We have received our orders from the Commander in Chief and we are moving out accordingly.”

But top Army and Air Force officials have warned Congress against moving so swiftly without taking into account the potential negative impact of suddenly allowing avowed homosexuals to serve in the armed forces. “I do have serious concerns about the impact of a repeal of the law on a force that is fully engaged in two wars and has been at war for eight and a half years,” Army Chief of Staff General George Casey told the House Armed Services Committee. “We just don’t know the impacts on readiness and military effectiveness.”

Similarly, Air Force Chief of Staff General Norton Schwartz told the committee that he is concerned that there is “little current scholarship on this issue” and wants to see further assessment from the Defense Department. “This is not the time to perturb the force that is, at the moment, stretched by demands in Iraq and Afghanistan and elsewhere without careful deliberation,” he said.

Longtime conservative commentator Phyllis Schlafly has been among those pointing out the obvious dangers of overturning a policy that has been standard operating procedure for any effective fighting force. In a recent commentary Schlafly noted that the primary purpose of the armed forces is “to prevail in combat, not to engage in leftist social engineering.” Nevertheless, she warned, “The left will not be satisfied until they have exacted their sexual agenda not only on Americans in civilian life through gay marriage, hate crimes legislation, and biased employer mandates, but on Americans in military life as well. We simply cannot allow the 1993 law to be repealed.”

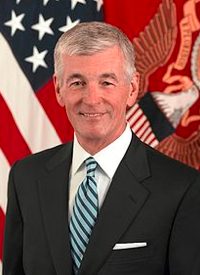

Photo: Army Secretary John McHugh