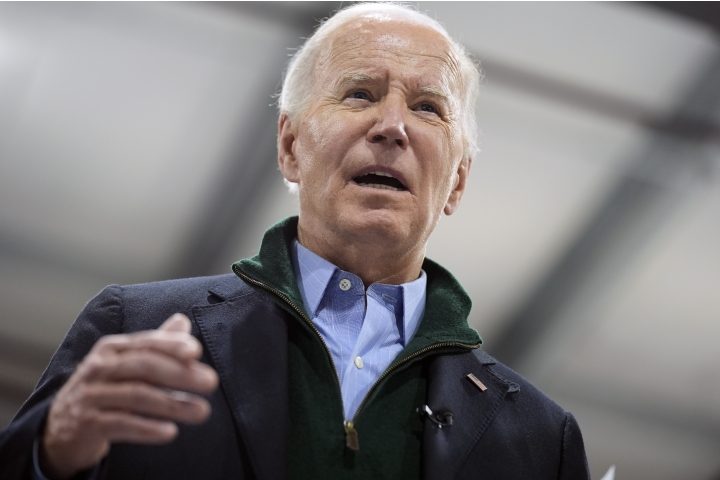

The joint military operation on Thursday evening by the United States and the U.K. against the Houthi rebels in Yemen, who have been disrupting international shipping in the Red Sea for several weeks, has received mixed reactions from Congress. There is bipartisan support but also some concern over President Joe Biden’s decision to take this action without broader consultation, which could potentially intensify the ongoing conflict in the Middle East.

In this coordinated effort, the armed forces of both nations targeted locations in Yemen under Houthi control through a series of airstrikes. Commenting to these actions, President Biden stated in a White House announcement, “I will not hesitate to direct further measures to protect our people and the free flow of international commerce as necessary.”

Representative Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) criticized the Biden administration for violating the constitutional separation of powers, declaring:

The President’s strikes in Yemen are unconstitutional. For over a month, he consulted an international coalition to plan them, but never came to Congress to seek authorization as required by Article I of the Constitution. We need to listen to our Gulf allies, pursue de-escalation, and avoid getting into another Middle East war.

A consistent supporter of the Constitution, Representative Thomas Massie (R-Ky.) echoed Khanna’s constitutional correction of the White House and praised his Democratic colleague for his courage in calling out the president: “Only Congress has the power to declare war. I have to give credit to [Rep. Ro Khanna] here for sticking to his principles, as very few are willing to make this statement while their party is in the White House.”

For decades, American presidents have assumed the authority to wage war, with combat operations being carried out in scores of battlefields across the globe.

As a matter of fact, Congress has not declared war since WWII.

Since the ratification of the current Constitution, the U.S. Congress has formally declared war on 11 occasions as part of five wars: first, the War of 1812; second, the War with Mexico (1846); third, the War with Spain (1898); fourth, World War I (1917); and, finally, as mentioned above, World War II (1941 and 1942).

Since WWII, then, there have been no “wars,” but there have been thousands of American soldiers, sailors, Marines, and airmen killed in combat, usually having been sent into harm’s way by the president acting alone.

Despite efforts over the years by presidents from both major political parties to prove the existence of executive war powers, the black letter of the Constitution, as well as the history of that document’s drafting and ratification, makes clear that Congress possesses the exclusive power to declare war.

It is true, however, that before putting “boots on the ground” in any of the theaters of combat opened in the last 77 years Congress could have declared war had the representatives and senators wished to do so. They have not done so, and don’t appear likely to resume the practice anytime soon.

It’s time to demand the policymakers take their own jobs as seriously as the men and women we ask to risk it all for our nation.

Doing so means restoring constitutional checks and balances. Congress has no greater responsibility than defending our country, and the Founders entrusted it with the power of declaring war because they wanted such a weighty decision to be thoroughly debated by the legislature instead of unilaterally made by the Executive branch.

As is the habit of The New American and The John Birch Society, we will provide insight from the Founders and from the Constitution itself on the issue of a president’s power to unilaterally make use of the military might of the United States, as well as his stiff-arming of the representatives of the people.

What the Founders Thought About Starting War

On August 17, 1787, delegates from 10 states began deliberating “on the clause ‘to make war’” at the Constitutional Convention. Charles Pinckney of South Carolina, a 29-year-old lawyer and planter, was the first to speak. Recorded in James Madison’s Notes of Debates, Pinckney argued for the Senate’s exclusive power to make war, criticizing the House for being too slow and too large for such decisions.

South Carolina’s Pierce Butler followed, advocating for presidential war-making authority. Butler “was for vesting the power in the President, who will have all the requisite qualities, and will not make war but when the nation will support it.”

Massachusetts delegate Elbridge Gerry countered, expressing shock at hearing “in a republic, a motion to empower the Executive alone to declare war.”

Virginia’s George Mason then voiced his opposition. “He was against giving the power of war to the Executive, because [he is] not safely to be trusted with it; or to the Senate, because [it’s] not so constructed as to be entitled to it.” He emphasized restricting war-making and easing peace-making. Mason, along with Gerry and Madison, suggested substituting “declare war” for “make war,” allowing the Executive to respond to immediate threats but not initiate conflict.

Roger Sherman of Connecticut supported this view, aligning with Madison that the executive “should be able to repel, and not to commence, war.” The convention’s president, George Washington, called a vote on the amendment, which passed with eight states in favor, one opposed, and one absent.

Rufus King clarified that while the legislature was to “declare” war, the “conduct” of war was an executive function. This distinction and the decision to place the declaration of war in legislative hands met no opposition in the state ratifying conventions.

Influenced by Emmerich de Vattel’s The Law of Nations, the Founding generation viewed war as a last resort. Vattel wrote, “The right of making war belongs to nations only as a remedy against injustice … it is the offspring of unhappy necessity.”

Thus, the Constitution grants “all legislative power” to Congress, indicating that only Congress can change a nation’s legal standing through war declarations.

This arrangement remained uncontested until Alexander Hamilton in President Washington’s Cabinet sought to realign this power, echoing the English constitution, favoring presidential authority in war declarations.

It was Hamilton’s zeal for converting the president into a monarch, and consequently empowering the former to wage war unilaterally as did the latter, that brought about one of the most enlightening and now forgotten episodes in our history, an episode that pitted Publius (the writer of The Federalist Papers) against himself!

James Madison: War-making Presidents Lead to Loss of Liberty

Within five years of the publication of The Federalist Papers (and four years of the ratification by the states of the Constitution), the co-authors of those seminal and influential essays on American political theory and constitutional interpretation were back at their desks once again, writing letters to the editors of newspapers.

This time, however, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton were not allies working to persuade others to commit to their common constitutional cause, but were opponents, striving through their letters to reveal each other’s perceived constitutional misdeeds to the American people. This episode in American history is known as the “Pacificus-Helvidius” debates, named for the pen names adopted by Hamilton and Madison, respectively.

In the first letter, Madison wrote that the power to declare war is “of a legislative and not an executive nature.” He continued that subject:

Those who are to conduct a war [the Executive Branch] cannot in the nature of things, be proper or safe judges, whether a war ought to be commenced, continued, or concluded. They are barred from the latter functions by a great principle in free government, analogous to that which separates the sword from the purse, or the power of executing from the power of enacting laws.

Madison was so strident in his insistence that the power to make war not be placed in the hands of the president, that his next letter (Helvidius No. 2) began with the bold pronouncement that if any president were to presume the war-making power, “No ramparts in the constitution could defend the public liberty or scarcely the forms of republican government.”

Did you get that?

James Madison warned us in 1793 that if Americans were to permit the president to make war, then the Constitution would not be able to protect us from tyranny!

Perhaps this is why the Helvidius letters are never studied in school anymore.

In additional warnings against allowing a president to make war, in another Helvidius paper, Madison made a clear and constitutionally sound statement on this subject of profound importance on the future of free government:

“Until war be duly authorized by the United States, they are actually neutral when other nations are at war, as they are at peace (if such a distinction in terms is to be kept up) when other nations are not at war.”

Finally, Madison explained, in Helvidius No. 4, why Americans must remain vigilant, keeping close watch over the actions of their elected representatives. To equal degree, though, Americans must be familiar with the powers granted to those representatives lest they claim to possess powers that are not enumerated in the Constitution.

Regarding the duty of Americans to learn for themselves and enforce on their elected leaders the limits of federal power set out in the Constitution, Madison wrote:

It is also to be remembered, that however the consequences flowing from such premises, may be disavowed at this time, or by this individual, we are to regard it as morally certain, that in proportion as the doctrines make their way into the creed of the government, and the acquiescence of the public, every power that can be deduced from them, will be deduced, and exercised sooner or later by those who may have an interest in so doing. The character of human nature gives this salutary warning to every sober and reflecting mind.

And the history of government in all its forms and in every period of time, ratifies the danger. A people, therefore, who are so happy as to possess the inestimable blessing of a free and defined constitution cannot be too watchful against the introduction, nor too critical in tracing the consequences, of new principles and new constructions, that may remove the landmarks of power.

And here we are. Americans have not been watchful and now “new principles and new constructions” are considered not only constitutional, but are praised by the leadership of both major political parties.