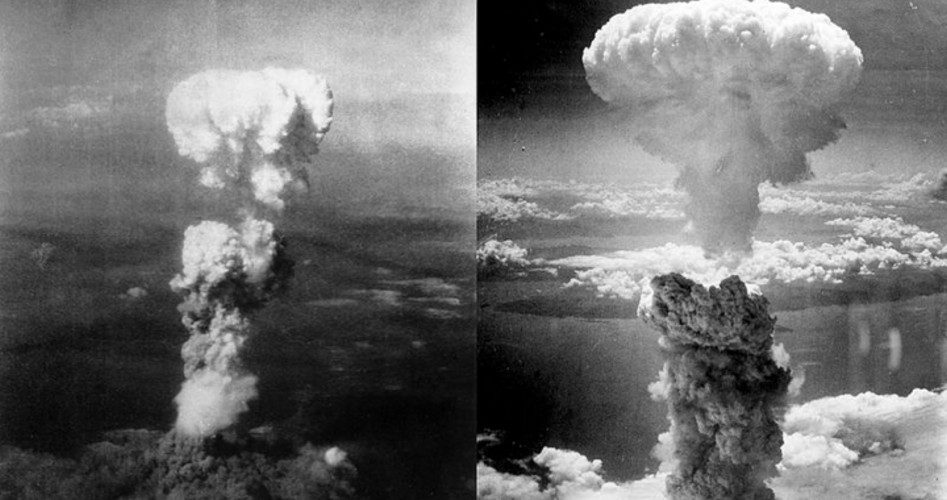

August 6 is the 70th anniversary of the dropping of atomic bomb by the United States on the Japanese city of Hiroshima (shown on left) — the first time such a weapon would be used against a civilian population. It was followed three days later by the dropping of a second atomic bomb on Nagasaki (shown on right). The two bombings killed an estimated combined total of 150,000 to 200,000 people, either from the immediate effects of the blasts or from the aftereffects of radiation poisoning.

Japan surrendered just 15 days after the second bombing on August 9, which was the same day that the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and invaded Manchukuo (Manchuria). Seven decades later, the bombings’ role in Japan’s surrender (and whether they were necessary to achieve that surrender), as well as the ethical justification for killing so many civilians, are still being debated.

The tragic event was commemorated today at an annual ceremony at Hiroshima’s Peace Memorial Park, drawing foreign ambassadors and dignitaries from 100 countries, including the United States. The Japan Times reported that the United States sent U.S. Ambassador to Japan Caroline Kennedy, for the second consecutive year and Rose Gottemoeller, undersecretary of state for arms control and international security, for the first time.

After observing a moment of silence to mourn those killed in the bombings, Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe reaffirmed his nation’s pledge to “eliminate nuclear weapons from the world.” Abe followed a theme common among those who blame the weapons themselves for the mass destruction and deaths — rather than the policy decisions to use them against civilians — when he said it was “disappointing” that world leaders were unable to reach a consensus on a final declaration during the ninth Review Conference of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in May. Abe said that Japan will submit a new resolution on the abolition of atomic weapons to the United Nations General Assembly in the fall, the Japan Times reported.

Hiroshima Mayor Kazumi Matsui joined Abe in calling for the abolition of nuclear arms, saying:

Policymakers in the nuclear-armed states remain trapped in provincial thinking, repeating by word and deed their nuclear intimidation.

People of the world, please listen carefully to the words of the hibakusha [surviving victims of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings] and, profoundly accepting the spirit of Hiroshima, contemplate the nuclear problem as your own.

The most common argument used to justify the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki 70 years ago was that a land invasion of Japan by U.S. forces would result in a very high number of Allied casualties, perhaps numbering in the millions. These figures were based on the premise — later demonstrated to have been false — that Japan would have refused to surrender had the bombings not taken place.

On July 26, 1945, just 11 days before the first bomb was dropped, the United States, Britain, and China released the Potsdam Declaration, which concluded: “We call upon the government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces, and to provide proper and adequate assurances of their good faith in such action. The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.”

Eleven days seems like a very hasty timeframe for unleashing such a devastating blow to an innocent civilian population. Japan was already largely in ruins as a result of prior U.S. conventional bombings. Surely, an invasion could have been put on hold for 30 days or more to give the Japanese bureaucracy time to consider the proposal. However, the widely held belief that Japan would not have surrendered without the atomic bombings is historically inaccurate.

The fact that most Americans accepted (and still accept) the premise however, explains why a 1945 Gallup poll indicated that 85 percent of the American public approved of the atomic bombings of Japan, and only 10 percent disapproved. However, that number has declined over the years, reported the Christian Science Monitor on August 6. The Monitor reported that the number of Americans who say the United States was justified in using the atomic bomb against Japan has dropped to 56 percent, according to a Pew Research Center poll conducted this spring.

However, the reasons for the decline in approval may be based not on the pros and cons of our military situation back in 1945, but on a growing fear of nuclear weapons. Allan Winkler, a professor of history at the Miami University of Ohio, offered such an explanation in a phone interview with the Monitor: “I think over the last 70 years, people have become more aware of what the nuclear age is and the consequences of it.”

When we consider the historic events of 1945, however, the moral justification and even the military justification for the atomic bombings begin to evaporate. An article posted by The New American on August 4, 2010 (“U.S. to Send First Delegation to Hiroshima A-Bomb Ceremony”) presented evidence that Japan actually tried to surrender long before Hiroshima and Nagasaki were destroyed. The following is an except from that article:

Among the best evidence making a case that the United States deliberately delayed Japan’s surrender to allow enough time for Germany to be defeated and for the Soviet Union to shift its attention away from the West and to enter the war against Japan, was presented in the 1956 book, The Enemy at His Back, by journalist Elizabeth Churchill Brown, the wife of noted Washington Star columnist Constantine Brown. Mrs. Brown had access to many of “the men who were no longer ‘under wraps,’” as she noted. She wrote, “With this knowledge at hand, I quickly began to see why the war with Japan was unprecedented in all history. Here was an enemy who had been trying to surrender for almost a year before the conflict ended.” In her book, Brown supplied abundant evidence about the treachery that prevented the Japanese from surrendering until the Soviets were able to enter the war against Japan and U.S. forces had dropped the atomic bombs on two Japanese cities. A sobering assessment was presented by Admiral William Leahy in his 1950 work I Was There, in which he discussed his reaction to the use of the bomb:

It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already beaten and ready to surrender…. It was my reaction that the scientists and others wanted to make the test because of the vast sums that had been spent on the project…. My own feeling was that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages.

In his article “Dropping the Bomb,” in the August 21, 1995 issue of The New American magazine, publisher John F. McManus further confirmed the pointlessness of destroying two cities and killing tens of thousands of civilians:

The first atomic bomb was exploded over Hiroshima on August [6], 1945; the second was detonated over Nagasaki [three] days later. On August [9]th, the Soviet Union declared war on an already beaten Japan. But other Japanese attempts to surrender had been coming fast and furious prior to these historically important developments. One of the most compelling was transmitted by General MacArthur to President Roosevelt in January 1945, prior to the Yalta conference. MacArthur’s communiqué stated that the Japanese were willing to surrender under terms which included:

• Full surrender of Japanese forces on sea, in the air, at home, on island possessions, and in occupied countries

• Surrender of all arms and munitions. Occupation of the Japanese homeland and island possessions by allied troops under American direction

• Japanese relinquishment of Manchuria, Korea, and Formosa, as well as all territory seized during the war.

• Regulation of Japanese industry to halt present and future production of implements of war.

• Turning over of Japanese which the United States might designate war criminals.

• Release of all prisoners of war and internees in Japan and in areas under Japanese control.

Amazingly, these were identical to the terms that were accepted by our government for the surrender of Japan seven months later.

When we seek to find an explanation for why our government would act in such an irrational and inhumane manner, we must ask the key forensic question often used in legal and police investigations to determine who has a motive for a crime — Cui bono? — which means, literally, “to whose benefit?”

First, who benefited from deliberately delaying Japan’s surrender, and second, who benefited from the dropping of the atomic bombs?

The prime beneficiary of delaying Japan’s surrender was the Soviet Union. The Japanese had first made surrender overtures through MacArthur to President Roosevelt in January 1945, but the Soviets were still fighting Germany, which didn’t surrender until May 7. Since the Western front near Berlin was nearly 5,000 miles from the Soviets’ Pacific port of Vladivostok, the Soviets required some time to shift their military resources that distance if they were to engage Japan. The U.S. refusal of Japan’s surrender offer bought them that time.

The atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki also ensured that Japan would be powerless when the Soviets went to war against the devastated nation. And so, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan the same day the atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, and were at war for just one week before Japan surrendered! In return for that token participation, the Soviets received the disputed Kuril Islands and Manchuria, where they found massive stores of arms that the Japanese kept there. The Soviets turned over these arms to the communist forces of Mao Tse-tung, enabling him to gain control of all of China. This also enabled the Chinese to support the communists in Korea, where the United States lost over 36,000 lives, and in Vietnam, where U.S. deaths exceeded 58,000.

Then there were the atomic bombings, themselves. They demonstrated a new horror that terrified the world and would produce a fear of a terrible nuclear holocaust that lasted throughout the Cold War. Following World War I, the internationalists who had established the old League of Nations were dismayed when the U.S. Senate refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles and to allow U.S. membership in the League. This time around, they needed a more convincing argument and the terrible example of what happened to Hiroshima and Nagasaki provided just the ammunition needed to frighten Americans into accepted the UN as mankind’s “last, best hope for peace.”

Furthermore, the internationalists who created the UN (and their communist allies) intended to give the international body control over the world’s nuclear weapons. U.S. Communist Party chief William Z. Foster wrote in an article appearing in the party newspaper Daily Worker on August 13, 1945: “If … the new atomic power which is a product of international science is to be directed to constructive uses, the general military control of it will have to be vested in the Security Council of the United Nations.”

This plan to turn over the world’s nuclear arsenal to the UN became more of a reality on September 25, 1961, when President John F. Kennedy presented to the 16th General Assembly of the United Nations a disarmament proposal entitled “Freedom from War: The United States Program for General and Complete Disarmament in a Peaceful World” (State Department Publication 7277).

After outlining the plan’s first two stages, the document states:

By the time Stage II [of the three-stage disarmament program] has been completed, the confidence produced through a verified disarmament program, the acceptance of rules of peaceful international behavior, and the development of strengthened international peace-keeping processes within the framework of the U.N. should have reached a point where the states of the world can move forward to Stage III. In Stage III progressive controlled disarmament and continuously developing principles and procedures of international law would proceed to a point where no state would have the military power to challenge the progressively strengthened U.N. Peace Force and all international disputes would be settled according to the agreed principles of international conduct. [Emphasis added.]

Had the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki not occurred, the concept of nuclear war would have been just an interesting theory, largely ignored by most. Because of the vivid images of the devastation of these two cities, however, nuclear war became the stuff nightmares were made of for several generations of Americans.

If the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were unnecessary to force Japan to surrender, they served another, darker purpose. They made Americans and the rest of the world so terrified that their own cities would be subjected to a similar fate, that they would be wiling to turn control over their nuclear arsenal to the UN to prevent nuclear devastation.

Along with the fear generated by the arms race between the old Soviet Union and the United States during the Cold War (during which the Soviets tested a 50 megaton bomb — 3,000 times more powerful than those dropped on Japan), Hiroshima and Nagasaki became the first examples of how nuclear blackmail could be used to frighten Americans into abandoning their national sovereignty.

The anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima commemorates a sad day in history, and its legacy stays with us in more ways than most people realize.

Related articles:

Dresden, Hiroshima, and Soviet Machinations

U.S. Ambassador Attends Hiroshima A-Bomb Ceremony