The week ended in Philadelphia with the temperature growing hotter and tempers getting shorter. Delegates sat in the old State House, suffering without ventilation (the secrecy rule required windows to be closed) while trying to hammer out a key provision of the new Constitution being drafted — representation in the House of Representatives.

In a curious breach of protocol, the 55 or so delegates present in Philadelphia on Friday, July 13, began a “long and excited debate” on a point which had not been referred to the committee, but was reported by it, nonetheless.

Readers of The New American will appreciate the fact that such assumption of authority was nothing new for the Constitutional Convention of 1787. As we have reported many times, from the very first day, the convention exceeded its mandate and, rather than recommend amendments to the Articles of Confederation, threw that constitution out and began negotiating a new charter.

The question being debated that day 227 years ago was whether in the House of Representatives each state should have one vote for every 40,000 inhabitants.

Before examining the particular points made by the delegates regarding this aspect of proportional representation, it is important to note that despite the allegations asserted by many modern historians that the Constitutional Convention of 1787 was nothing less than the landed aristocracy protecting their privilege, when the opportunity arose in the convention to directly prefer property to non-property, the vote went against any such arrangement.

With population established as the measure that would determine representation, the convention had to amend a provision passed earlier that called for the number of representatives allotted to each new state to be determined by “wealth and the number of inhabitants.” The word wealth was accordingly stricken from the measure and debate on the proportion continued.

Earlier in the debates, the line of cleavage was between the large and the small states regarding the question of representation in the Senate. When the same question was being worked out with regard to the House of Representatives, those blocs dissolved and the north versus south situation dominated.

It was universally believed that growth in the south would outpace that of the north and so the ratio that eventually was approved in the final version of the Constitution was one representative per 30,000 inhabitants. This way, the south’s control of the House of Representatives would be delayed.

With the compromise constitutional ratio (1:30,000) in mind and given that the U.S. Census Bureau reports that there are currently 313.9 million inhabitants of the United States, if the Constitution were being followed, there should be approximately 10,463 members of the House of Representatives.

As any junior high school civics student can attest, there are only 435 members of that body, just four percent of the constitutionally established ratio!

Why, then, are Americans not represented according to the ratio set forth in the Constitution?

It is because of laws passed by Congress in 1911 and in 1929. At the time of the debate on the bill setting the arbitrary limit on the number of representatives, Representative Ralph Lozier (D-Mo.) made the following seemingly obvious observation:

I am unalterably opposed to limiting the membership of the House to the arbitrary number of 435. Why 435? Why not 400? Why not 300? Why not 250, 450, 535, or 600? Why is this number 435 sacred? What merit is there in having a membership of 435 that we would not have if the membership were 335 or 535? There is no sanctity in the number 435…. There is absolutely no reason, philosophy, or common sense in arbitrarily fixing the membership of the House at 435 or at any other number.

Crunching the numbers reveals that for nearly 90 years, Americans have been the least represented population since the ratification of the Constitution (and the 1:30,000 representation ratio) in 1789.

In America today, each member of the House represents, on average, 721,609 Americans! For a bit of context, in 1913, two years after the bill setting the magic number of representatives at 435 was passed, each congressman represented only 200,000 Americans — still unconstitutional, but much closer to the correct constitutional proportion.

Obviously, the immense imbalance in the House of Representatives has many ill effects. First, the influence of lobbyists is increased. The larger the pool of potential donors per each representative, the more money special interests are able to raise, thus decreasing proportionally the influence of individual voters.

Additionally, the Founders’ concerns about a lack of representation are borne out when a representative is expected to know the opinions of over 700,000 people.

James Madison expressed the need for constituents to feel connected to their representatives to the national legislature. In Federalist No. 57 he wrote,

The house of representatives .. .can make no law which will not have its full operation on themselves and their friends, as well as the great mass of society. This has always been deemed one of the strongest bonds by which human policy can connect the rulers and the people together. It creates between them that communion of interest, and sympathy of sentiments, of which few governments have furnished examples; but without which every government degenerates into tyranny.

And in another Federalist letter:

The members of the legislative department … are numerous. They are distributed and dwell among the people at large. Their connections of blood, of friendship, and of acquaintance embrace a great proportion of the most influential part of the society … they are more immediately the confidential guardians of their rights and liberties.

This issue should be front and center in 2014 as November elections approach. Nearly every candidate appealing to constitutionalists has committed to eliminating the influence of special interest. Repealing the Reapportionment Act of 1929 would do more to accomplish that worthwhile aim than most other proposals. Not to mention the fact that such a solution would have the added benefit of being a return to strict constitutional principles.

The concept of subtraction by addition is a difficult one to comprehend, perhaps. That is to say, no one who flies the flag of the Constitution advocates an increase in the size of government. However, there is a possibility that by removing the 435-member ceiling and requiring representatives to reduce staff and take a significant pay cut (so as not to increase by one cent the amount of money spent on congressional salaries and staff), a lifetime spent in Congress might not be so enticing, and the increased turnover rate will please Americans of a Jeffersonian bent who long for a “revolution” every couple of decades.

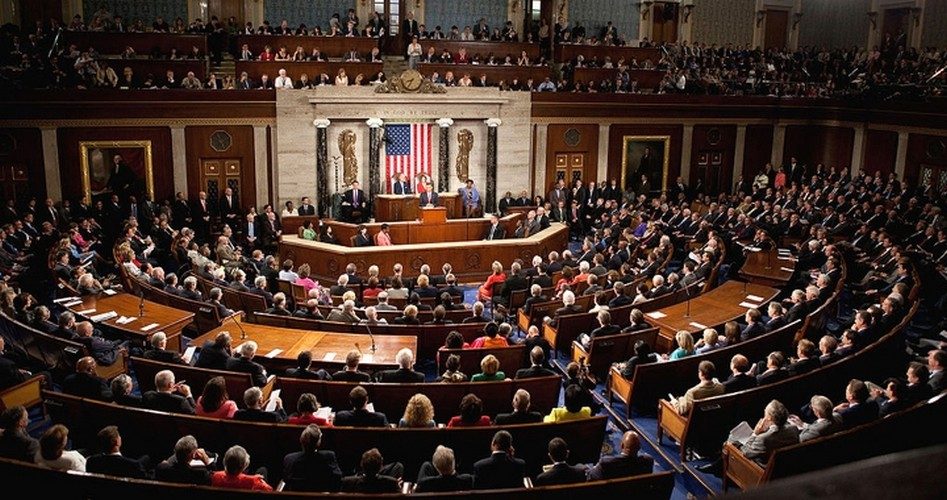

Photo of U.S. House of Representatives Chamber in Washington, D.C.

Joe A. Wolverton, II, J.D. is a correspondent for The New American and travels nationwide speaking on nullification, the Second Amendment, the surveillance state, and other constitutional issues. Follow him on Twitter @TNAJoeWolverton and he can be reached at [email protected].