Both major party candidates for president have advocated policies that violate basic rights and ignore the U.S. Constitution.

For example, during the debate held on September 26, Hillary Clinton, the Democratic Party’s nominee for president and Donald Trump, her Republican rival, put aside their professed differences to join in a call for the contraction of the right to keep and bear arms and the right to be free from unwarranted searches and seizures. Specifically, both candidates agreed that anyone finding himself on the “no-fly list” or the “watch list” should be disqualified from gun ownership.

“We finally need to pass a prohibition on anyone who’s on the terrorist watch list from being able to buy a gun in our country. If you’re too dangerous to fly, you are too dangerous to buy a gun,” Clinton said.

Trump stated, “First of all, I agree, and a lot of people even within my own party want to give certain rights to people on watch lists and no-fly lists. I agree with you. When a person is on a watch list or a no-fly list … and I have the endorsement of the NRA, which I’m very proud of.”

The problems with this proposal are manifold and are fundamental to the American concepts of justice, due process, and liberty.

First, being on a “no-fly list” does not mean a person is a “terrorist.” There is a requirement of due process that must be followed before a suspect becomes a convict. To skip this aspect of liberty would deal a blow to over 600 years of Anglo-American constitutional progress.

It is this due process that for those several centuries has stood between the despotism of the governors and the liberty of the governed.

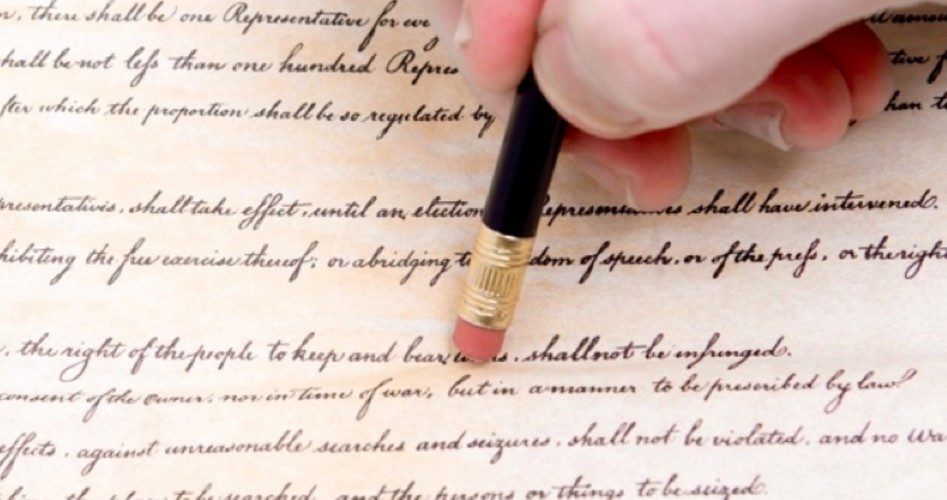

Next, the Constitution — the source of all lawful federal authority — grants to the general government neither the power to create lists of personae non gratae nor to subject those people to a summary deprivation of their liberty.

To some, this would suggest that there remains no protection for passengers on the nation’s thousands of flights. In the absence of government intervention, many say, there will be no way to safeguard the skies.

False.

No organization would have more to lose from a lack of security on planes than the airlines themselves. As private sector companies, the airlines could hire private security to enforce their own safety standards, without infringing in any way whatsoever on the freedom of fliers.

For example, if a particular airline’s security personnel felt that a passenger posed an unwelcome risk to other passengers, the former could be denied service without depriving him of his right to due process, a requirement for government actions, not those of a private entity.

What’s more, this approach to airline safety would provide passengers with a choice of carriers, undoubtedly leading to the increased prosperity of the airline that boasts of the safest history of incident-free flights.

And what would be perhaps the most welcome of all results of this free market solution is the elimination of the need for that most hated of all the quasi-government goon squads: the TSA.

The bottom line is that this approach advances the causes of decentralization, capitalism, competition, and consumer choice, all of which would work together to produce safer air travel while leaving liberty completely intact.

During his debate with Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump also advocated for the return of the law-enforcement practice known as “stop and frisk.” He declared that this practice helped reduce crime in New York City, where it was once officially applied by police in Gotham in contravention of due process and the Fouth Amendment.

Before analyzing whether the data support Trump’s statement, a brief explanation of the tactic is in order. An article published by the Cato Institute summarized “stop and frisk”:

Stop and frisk, as practiced in cities like New York and Chicago, refers to police detentions and searches of people with virtually no individual suspicion of wrongdoing. Advocates of the program insist that the Supreme Court’s ruling in Terry v. Ohio, allowing frisks where the police can articulate reasonable suspicion of criminal behavior, supports the practice, but that’s a far cry from the standard the NYPD used for years.

Police routinely cited “suspicious” behaviors such as “fidgeting,” “changing direction,” “looking over his shoulder,” and “furtive movements” to justify stops and searches of innocent New Yorkers. And the brunt of this policy was disproportionately borne by people of color (roughly half of the stops targeted black citizens, and roughly a third targeted Hispanic citizens, despite the fact that stops of white people were more likely to produce contraband).

Under stop and frisk, New Yorkers were stopped hundreds of thousands of times each year. Before the program was reformed in 2013, between 85% and 90% of those hundreds of thousands of stops uncovered no wrongdoing at all. In other words, the vast majority of people who were detained and searched by the government were not “bad people,” they were innocent New Yorkers going about their day.

In August 2013, federal Judge Shira Scheindlin held that the NYPD’s execution of former mayor Michael Bloomberg’s version of “stop and frisk” was no less than a “policy of indirect racial profiling” that was carried on disproportionately in minority communities. Judge Scheindlin found that police officers were frequently stopping and frisking “blacks and Hispanics who would not have been stopped if they were white.”

She held that the practice violated the protections afforded by the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which reads: “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

So-called stop and frisk encounters regularly failed to clear the constitutional barriers between the power of the police and the civil liberties of the people they are supposed to serve and protect.

Finally, as for Trump’s claim that the stop-and-frisk scheme carried out in New York City reduced crime, the data don’t lie and they don’t back up Trump’s testimony.

Studies conducted by Columbia University reveal that New York’s stop-and-frisk program “was not associated with reduced crime when the practice was indiscriminate.” In an article analyzing the study’s findings, the New York Times reported: “The stop-and-frisk policy was ineffective because civilians were regularly stopped on inconsequential pretexts and vague justifications, such as that a person was moving furtively. The result was officers wasting their time with civilians who were not criminals.”

These revelations should remind Americans that no one should have to walk down the street fearful that police will stop and search them when they have done nothing to arouse suspicion. This is not only a constitutionally propounded protection of liberty, but in cities and towns patrolled by militarized police and the well-publicized fatal interactions between those cops-turned-warfighters and citizens, it seems ill-advised to unnecessarily multiply the incidents of interaction between police and the people.

A practice such as stop and frisk, which has been proven to put innocent, law-abiding people at risk of being searched by an overzealous police force, could only serve to increase the violent atmosphere surrounding so many of our communities.

Law, order, peace, and justice would all be better served by keeping law enforcement under local control and absolutely free from federal interference or influence (any amount of which would violate statutes and the Constitution) and by eliminating the frequently egregious and regularly repugnant interaction between airline passengers and the TSA.

The solution is simple: The American people — who retain ultimate sovereignty — must demand that no one be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process and that no one be subjected to searches by government agents in the absence of the reasonable suspicion required by the Fourth Amendment.

As for the Second Amendment, it is the keeping and bearing of arms by the people (and their organized militias) that the Founders intended would serve as the final barrier between the people and the states, and the government they created to serve them.