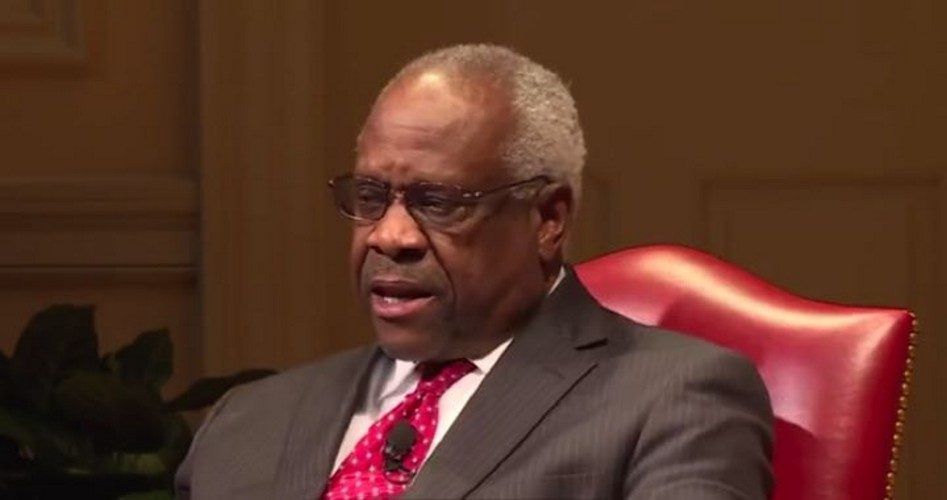

Clarence Thomas is perhaps the one true constitutional originalist left on the U.S. Supreme Court. Often known as the “great dissenter,” he has often gone alone in writing opinions in order to defend not only his own principles, but those of the Constitution itself.

In his dissent in Obergefell v. Hodges, the landmark case that paved the way for homosexual marriage in the United States in 2015, Thomas wrote: “The Court’s decision today is not only at odds with the Constitution, but with the principles upon which our Nation was built. Since well before 1787, liberty has been understood as freedom from government action, not entitlement to government benefits.”

We need more justices like Clarence Thomas.

With Anthony Kennedy’s resignation last year, Thomas is now the longest-serving justice on the Supreme Court. Now 70, an age when most of us are beginning to enjoy retirement, Thomas shows no signs of stepping down. And as the longest-serving member, Thomas may now be in a position to pull the court in his direction on key cases.

Ralph Rossum, the author of Understanding Clarence Thomas: The Jurisprudence of Constitutional Restoration, describes Thomas’ influence thusly: “He stakes out a position more forthrightly or vigorously than other justices are willing to go, but they’re kind of sucked along in his wake,” Rossum said, adding, “Thomas drags the court in his direction. They may not go as far as he goes, but they go further than they would otherwise.”

Over his 27 years on the court, Rossum believes that Thomas has moved the court closer to his position on voting rights, campaign finance, and the Second Amendment.

And Thomas is not mellowing with age. In February, he wrote against the landmark 1964 libel case the New York Times v. Sullivan and similar cases, calling them, “policy-driven decisions masquerading as constitutional law.” Thomas added, “We should not continue to reflexively apply this policy-driven approach to the Constitution.”

He has also equated Roe v. Wade with the infamous Dred Scott decision. Along with that, Thomas wrote an opinion chastising his colleagues for declining to hear cases about some states’ efforts to strip Medicaid money from Planned Parenthood, which Thomas called, “abdicating our judicial duty.” Both Gorsuch and Alito agreed with him.

The Supreme Court is one place left in society where its members value experience over expediency. Look at the Left’s worship of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Eighty six years old and held together with duct tape and chicken wire, Ginsburg is an icon of the progressive movement. Movies are made about her, and people have offered their own body parts to keep her alive.

But unlike Ginsburg, Thomas shies away from notoriety, rarely accepting invitations to speak and hardly ever even asking questions when court is in session. In fact, in March when Thomas asked a question during a case, it was front-page news. Thomas is clearly not on the Supreme Court for the notoriety, but because he loves America and the Constitution.

The job of a Supreme Court justice is to apply the Constitution to court cases, not make law by judicial fiat. Unlike some of his colleagues, Thomas understands this. His colleagues, particularly Kavanaugh, Gorsuch, Alito and, especially, Chief Justice Roberts would do well to emulate him.

Image of Clarence Thomas: Library of Congress