The U.S. Army Court of Criminal Appeals heard arguments October 11 regarding the future of accused Ft. Hood shooter Major Nidal Hasan’s beard. As we reported in August, Hasan has grown a beard while incarcerated, awaiting trial on the charges that he attempted to murder 32 people during an armed rampage at a deployment processing center at Ft. Hood, Texas.

Hasan thinks pleading guilty and growing a beard will keep him out of hell. At the hearing held on August 15, however, the military officer presiding over the court martial of the one-time U.S. Army psychiatrist rejected Hasan’s guilty plea and told him that he would order the devout Muslim to be forcibly shaved before the trial begins. This decision is the basis for the appeal.

“He does not wish to die without a beard as he believes not having a beard is a sin,” the Associated Press reports, quoting from the appeal filed by Hasan’s defense counsel with the appellate court clerk.

Judge Goss ruled that the beard is a distraction and pointed out that it is a violation of Army regulations. Goss will not allow Hasan to enter the courtroom until he complies with the regulation and has fined him $1,000 for failing to comply with the order. The Associated Press reports that Goss wants Hasan in the courtroom so that he cannot use his absence from the proceedings as a basis for a subsequent appeal should he be found guilty.

Army prosecutors claim that Hasan’s reason for growing the beard was less spiritual and more pragmatic. They insist that Hasan wants to make it hard for witnesses to identify him.

In December 2009, Army prosecutors charged Hasan with 32 counts of attempted murder in connection with the victims wounded in his armed rampage at Ft. Hood, Texas, on November 5. Among those injured by Hasan were the two civilian police officers who eventually fired on Hasan and brought him down, ending the massacre. These lesser charges are in addition to the 13 counts of murder with which the former army psychiatrist and alleged jihadist was charged.

On the day of the shooting spree, Hasan reportedly entered the center for soldiers awaiting deployment to Afghanistan and Iraq, brandished two pistols, and climbed on a table and opened fire. Then, targeting first those in uniform, Hasan shouted “Allahu Akbar!” — Arabic for “God is Great.”

Federal investigators claim that Hasan’s “militancy” was influenced by the late American-born Muslim cleric Anwar al-Awlaki. President Obama placed Awlaki on his infamous (and illegal) kill list and on September 30, 2011, while Awlaki was eating breakfast in Yemen, two unmanned Predator drones fired two Hellfire missiles, killing him.

Disregarding the sideshow that the beard issue has become, there is a legitimate and important constitutional conflict at the heart of the matter. That is, as a soldier, is Hasan’s constitutional right to freely exercise the religion of his choice in effect, or is it superseded by the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ)?

In an informative blog devoted to exploring issues of conflicts between military and constitutional law, the basic guidelines relevant in this conflict are set forth.

Many servicemembers find that there are conflicts between the requirements of their religion and the rules governing military life. People who wear religious clothing, such as yarmulkes or veils or whose beliefs require them to eat specific foods or worship at particular times often find their commands unsympathetic to their needs. A servicemember’s freedom to practice his or her religious beliefs will be accommodated “when accommodation will not have an adverse impact on military readiness, unit cohesion, standards, or discipline.” When there is continued “tension between the unit’s requirements and the individual’s religious beliefs, commanders are instructed to consider assignment, reassignment, reclassification, or separation” as well as punishment under the UCMJ.

The standards cited above come from Department of Defense Instruction 1300.17. This document “prescribes policy, procedures, and responsibilities for the accommodation of religious practices in the Military Services.”

In the instructions, the prevailing policy is defined regarding the accommodation of religious practice while in military service. Section 4 reads:

The U.S. Constitution proscribes Congress from enacting any law prohibiting the free exercise of religion. The Department of Defense places a high value on the rights of members of the Military Services to observe the tenets of their respective religions. It is DoD policy that requests for accommodation of religious practices should be approved by commanders when accommodation will not have an adverse impact on mission accomplishment, military readiness, unit cohesion, standards, or discipline.

Although the wearing of beards isn’t specifically addressed by the instruction, Section 3 (b) does exclude “hair and grooming practices required or observed by religious groups” from the definition of accepted religious apparel. With that exception in mind, it is informative to read the rule regarding the wearing of such clothing and jewelry.

Rule 5 under the “Procedures” heading mandates:

In accordance with section 774 of Reference (c), members of the Military Services may wear items of religious apparel while in uniform, except where the items would interfere with the performance of military duties or the item is not neat and conservative. The Military Departments shall prescribe regulations on the wear of such items. Factors used to determine if an item of religious apparel interferes with military duties include, but are not limited to, whether or not the item:

1. Impairs the safe and effective operation of weapons, military equipment, or machinery.

2. Poses a health or safety hazard to the Service member wearing the religious apparel and/or others.

3. Interferes with the wear or proper function of special or protective clothing or equipment (e.g., helmets, flak jackets, flight suits, camouflaged uniforms, gas masks, wet suits, and crash and rescue equipment).

4. Otherwise impairs the accomplishment of the military mission.

Regarding the wearing of beards generally, Army Regulation 670-1-1-8(a)(2)(c) mandates that “males will keep their face clean-shaven when in uniform or in civilian clothes on duty,” mentioning specifically that “beards are not authorized.”

Relevant to this important debate is the fact that relevant military regulations do not require that the religious practice for which a serviceman seeks accommodation be a requirement of that religion. The instruction sets the threshold much lower by allowing exceptions to be made based on the soldier’s own interpretation of the demands of his religion.

Read together, however, DoD Instruction 1300.17 and Army Regulation 670-1 would seem to make Hasan’s appeal an open-and-shut case with regard to the wearing of a beard, even as an expression of his religious beliefs. Congress has authorized the Department of Defense to proscribe certain religious expression and the Pentagon accordingly has issued rules forbidding the wearing of beards.

An important related inquiry that has not been made, however, is whether it is constitutional for Congress — the body whose actions are specifically restricted by the First Amendment — to allow a department of the executive branch to prohibit religious expression that is explicitly protected by the Constitution. That is, how is it legal for Congress to authorize one branch to do something that it is forbidden from doing itself?

That would be the case if it wasn’t for an exception to the zero tolerance policy on beards. In the regulation cited above, the Army provides that a soldier may wear a beard if it is prescribed by a medical authority.

It seems incongruous at best for the Army to carve out an exception for beards based on medical exigencies and not for the practice of one’s religious faith. Viewed objectively, this situation points to a U.S. armed force that is more tolerant of physical than spiritual needs. For the Pentagon that should be a difficult position to defend, particularly in light of the fact that the Constitution explicitly protects the latter from infringement by the federal government.

Whether or not the appeals court addresses this critical question of constitutional conflict of law, such a question must be addressed in order to maintain unit cohesion in a military composed of members of diverse religious devotion.

It is not known when the Army court of appeals will issue a ruling in Hasan’s case. Which ever way it comes down, the decision is likely to be appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces, the highest appeals court in the military judicial system.

A story in the Los Angeles Times reports that if the court ultimately rules against Hasan, he must shave voluntarily or he will be held down and have it removed forcibly by military guards.

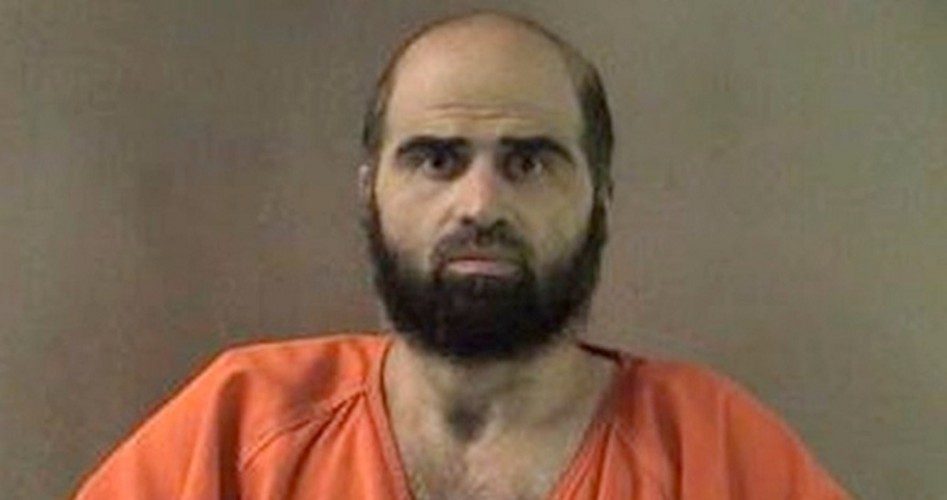

Photo of Major Nidal Hasan: AP Images