“If these people are radicalized and they don’t support the United States and they are disloyal to the United States as a matter of principle, fine. It’s their right, and it’s our right and obligation to segregate them from the normal community for the duration of the conflict.”

Thus spoke retired General Wesley Clark, a former Democratic Party presidential candidate, in an interview on MSNBC this past Friday.

Back in 2004, Clark, the former supreme allied commander of NATO, was harshly critical of what he considered the Bush administration’s excessive response to the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center towers and the Pentagon.

But since then, he has drastically altered his position, now strongly supporting the use of domestic internment camps, specifically citing those where Americans of Japanese ancestry were sent during World War II. (There were also camps for Germans and Italians, but in much smaller numbers.)

While many would have agreed with Clark’s earlier assessment that Bush went too far in his reaction to the 9/11 attacks, citing actions such as the PATRIOT Act’s reduction of civil liberties, Bush never suggested anything nearly as sweeping as that now proposed by Clark.

One can certainly understand arresting, trying, and incarcerating any person conspiring to commit acts of violence inside the United States; however, Clark’s proposal is chilling to constitutionalists. He is advocating going after those who are not only not involved in a conspiracy to commit terrorist acts, but who have not even yet been radicalized. “We have got to identify the people who are most likely to be radicalized,” he asserted. “We’ve got to cut this off at the beginning.”

“I do think on a national policy level we need to look at what self-radicalization means because we are at war with this group of terrorists,” Clark added.

Americans are understandably concerned about Islamic terrorism. Those who either commit or conspire to commit acts of violence should be arrested and prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law. But the idea of sending to internment camps those who might become radicalized, and might conspire to commit violence is absolutely chilling.

Once such a precedent has been set, who might the next target of the federal government be? The Obama administration considers members of patriotic organizations such as The John Birch Society, Eagle Forum, and the Tea Party to be extremists. Some even regard pro-lifers or evangelical Christians as “radicals.”

Who would decide which individuals would be sent to these internment camps? During World War II — Clark’s model — it was one man: President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

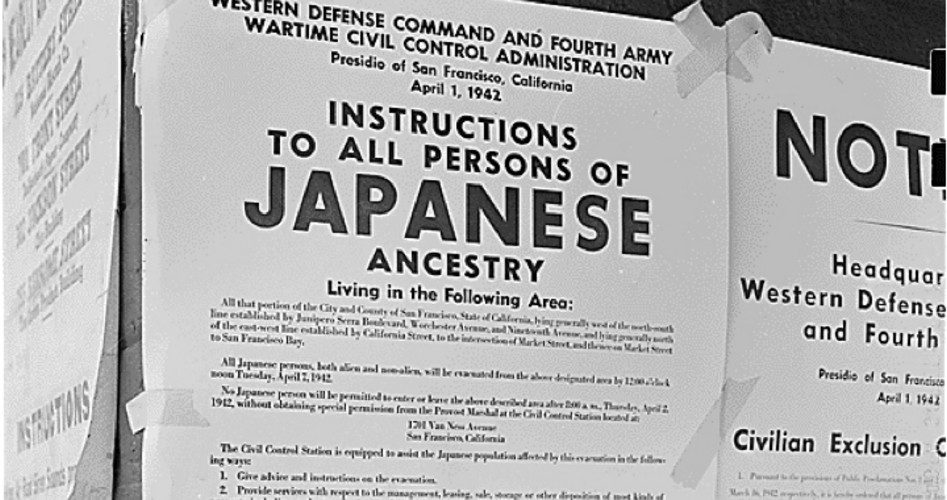

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, commanding that Japanese Americans be relocated away from the West Coast and into internment camps — without any due process, proof of disloyalty, or regard to American citizenship. This draconian policy led to the eventual incarceration of over 100,000 people, 62 percent of whom were U.S. citizens.

After Japan’s “Meiji Restoration” in 1868, in which Emperor Meiji wrested power back from the warlords and began the modernization and industrialization of his country, many Japanese had taken advantage of the opportunity to emigrate to the United States.

In 1936, as relations between the United States and Japan were souring, Roosevelt directed the Office of Naval Intelligence to create a list of “those who would be the first to be placed in concentration camps in the event of trouble” between Japan and the United States.

However, as the two nations moved closer to war, Charles Munson of Naval Intelligence delivered a report on November 7, 1941, that “certified a remarkable, even extraordinary degree of loyalty among this generally suspect ethnic group.” FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover supported Munson’s findings, contending to Roosevelt that the Japanese posed no espionage threat.

Despite this, FDR issued his order and appointed Lt. General John DeWitt, head of Western Command, the administrator of the internment program. “A Jap’s a Jap,” DeWitt explained, when reporters queried him about “loyal” Americans who just happened to have Japanese ancestry. DeWitt told Congress, “I don’t want any of them here. They are a dangerous element…. It makes no difference whether he is an American citizen; he is still a Japanese…. But we must worry about the Japanese all the time until he is wiped off the map.”

The attorney general of California — Earl Warren, later the chief justice of the Supreme Court — argued for the federal government to remove all Japanese from the West Coast. On February 2, 1942, the Los Angeles Times even editorialized of those Americans of Japanese ancestry, “A viper is nonetheless a viper, wherever the egg is hatched.”

Some of the interned Japanese chose to join the U.S. armed forces, ironically to “fight for liberty,” and were sent to the European theater. The bulk of them fought in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which emerged from the war as the most highly decorated U.S. military unit of its size, earning the nickname “the Purple Heart division.” Historian John Toland tells the story of an American prisoner of war who witnessed a battle between Germans and the 442nd. When a German soldier expressed to him surprise that they were having to fight Japanese, the American soldier advised the German that he’d been taken in by Hitler’s propaganda. The Japanese, he informed the German, are really on “our side.”

While the 442nd fought for America, most Americans of Japanese blood languished in the camps, which were cramped, with little room for privacy. One camp in Wyoming even had unpartitioned toilets. As the war progressed, conditions did improve in the camps, and life went on, with schools, such as they were, activities, including baseball games, and the like.

Eventually it became obvious that the incarceration had no good purpose; however, FDR opted to delay the release of the interned prisoners until January of 1945, so as not to endanger his reelection chances in 1944. In this decision he ignored the advice of both FBI Director Hoover and War Relocation Authority (WRA) director Dillon Myer that the internment should end in 1944.

The WWII internment camps are just what General Clark has in mind as a model for today. And he is not alone. Prominent neoconservative Daniel Pipes has called internment “a good idea” which offers “lessons for today.” And Michelle Malkin, in her book In Defense of Internment: The Case for Racial Profiling in World War II and the War on Terror, was blunt, declaring: “Civil liberties are not sacrosanct.”

Despite the clear protections of civil liberties in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, in 1944 the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in the case of Korematsu v. the United States that the internment camps did not violate the Constitution.

Former Supreme Court Justice Tom Clark, who assisted the U.S. Department of Justice in effecting the “relocation” of the Japanese, addressed this issue in the epilogue of his 1992 book, Executive Order 9066: The Internment of 110,000 Japanese-Americans:

The truth is — as this deplorable experience proves — that constitutions and laws are not sufficient of themselves…. Despite the unequivocal language of the Constitution of the United States that the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, and despite the Fifth Amendment’s command that no person shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law, both of the constitutional safeguards were denied by military action under Executive Order 9066.

The actual “lesson for us today” is not that we need to reimplement internment camps, but rather that all American citizens must develop a renewed respect for the protection of their civil liberties enshrined in the Constitution and Bill of Rights.