In an expertly written article published online earlier this month in The New American, Bruce Walker reported on comments made by Justice Breyer during an appearance on the television talk show Fox News Sunday.

In that interview, Justice Breyer explains that his dissent in the landmark case of District of Columbia v. Heller is soundly based in the circumstances surrounding the wording and eventual passage of the Second Amendment. That regularly debated part of the Bill of Rights was, as with most of the others, introduced by the illustrious James Madison in the First Congress.

Justice Breyer’s version of the history of the ratification of the Bill of Rights is curious, especially in light of the facts. As recounted by Walker:

In his opinion in that case, Breyer stated that James Madison included the language of the Second Amendment so that the states would ratify the Constitution.

As Walker then points out, Breyer’s assessment of the situation at the time of the ratification of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights is partially true. There was certainly an influential cadre of founders who acquiesced to the ratification of the original Constitution only with the understanding that there would be a bill of rights appended to the document as soon as practicable.

Fortunately, there are those who have made a thorough study of the Founding Era and the historic events that occurred in those days. One of the preeminent scholars in the field is Pauline Maier. Ms. Maier’s superbly crafted books have been reviewed in The New American, in fact.

Indeed, few authors are abler than Pauline Maier when it comes to the crucial task of presenting the Founding Era in a manner accessible to a broad audience without sacrificing the exactness required of respectable scholarship. Maier is the William Rand Kenan, Jr. professor of American History at MIT, and her back catalog includes the seminal American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence, a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle award. Consistently, Maier’s pen glides deftly across the page, and the result is always readable, quotable, and recommendable.

Not surprising, given her level of expertise and skill at writing, Maier recently penned what amounts to a refutation of the cockeyed chronicle of events offered by Justice Breyer on Fox News Sunday.

In an op-ed published on December 21 in the New York Times entitled “Justice Breyer’s Sharp Aim,” Maier provides a crucial bit of historical context (and truth) to the tale woven by Breyer. Speaking of Breyer’s appearance on Fox News Sunday, Maier writes:

He [Justice Breyer] said that James Madison wrote the Second Amendment because some Americans feared that Congress would call up the state militias and nationalize them. Madison proposed the amendment, the justice said, to appease these skeptics and to "get this document ratified." Justice Breyer continued: "If that was his motive historically, the dissenters were right. And I think more of the historians were with us."

Maier then proceeds to rebut that take on Madison’s motives.

There is a problem with this argument: by the time Madison proposed what became the Second Amendment on June 8, 1789, the Constitution had already been ratified and was in effect. Rhode Island and North Carolina had yet to ratify, but it’s hard to believe that Rhode Island, with its many Quakers, would be enticed into the Union by an amendment affirming the right to bear arms.

The record of the legislative history of the Second Amendment is illustrative here. As Ms. Maier rightly informs readers, the measure that would become the Second Amendment was brought to the floor of the House of Representatives on June 8, 1789, during the first session of Congress. The originally proposed language relating to arms was worded this way:

The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed; a well armed and well regulated militia being the best security of a free country but no person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms shall be compelled to render military service in person.

After some debate and revision by Madison’s fellow representatives, the version of the passage as sent to the Senate for deliberation read as follows:

A well regulated militia, composed of the body of the people, being the best security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed; but no one religiously scrupulous of bearing arms shall be compelled to render military service in person.

When the measure was returned to the House for reconsideration and vote, the Senate had reworked the language again:

A well regulated militia being the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.

On September 21, 1789, the House of Representatives approved the changes made by the other chamber and the amendment accordingly was entered into the House journal. However, there was one change made during the transcription. The words “necessary to” were added after “A well regulated militia being….”

Finally, as recently described in an article by this author in The New American, the Bill of Rights was adopted on December 15, 1791, having been ratified by three-fourths of the states as required by the Constitution.

With this bit of historical context in mind, one sees how Justice Breyer is inventing history for the sake of a good story, which in turn is used as the basis for a ruling on the constitutionality of the right of citizens to bear arms.

An elegantly simple synopsis of recent Court decisions is delivered by Pauline Maier at the conclusion of her New York Times piece:

Thanks to the decision in Heller, an individual right to bear arms is now established in American law. And in Heller’s sequel, McDonald v. Chicago, the court majority last summer said the states are bound by the Fourteenth Amendment to honor that right.

It is pleasing to read the well regarded opinion of a member of academia, a claque so often vociferous in their peer-reviewed denunciation of the Founders and the right to bear arms as protected in the Bill of Rights.

Now the vital question is whether we the people and the several states will be successful in our insistence for our natural right of self-defense, a right which protects us most securely against the rise of tyranny.

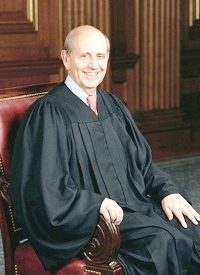

Photo: Stephen Breyer