In the current national controversy for the calling of an Article V convention, opponents have experienced two setbacks this year, when West Virginia and Oklahoma approved applications for a Balanced Budget Amendment (BBA) Article V convention. It was past time to “Win one for the Gipper,” and the state of Delaware just did it.

Last week, a resolution in the state’s legislature to rescind all previous calls for an Article V convention passed the Senate by a wide margin (16-4) following passage in the House of Representatives by 25-11. The legislation listed eight “live” (unrescinded) calls dating to 1907 for such a convention, and this bill canceled them all. Among them was a 1976 application for an Article V convention on the topic of a highly suspect Balanced Budget Amendment.

The U.S. Constitution provides two mechanisms for amending the document, outlined in Article V. It reads thus,

The Congress, whenever two thirds of both houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose amendments to this Constitution, or, on the application of the legislatures of two thirds of the several states, shall call a convention for proposing amendments, which, in either case, shall be valid to all intents and purposes, as part of this Constitution, when ratified by the legislatures of three fourths of the several states, or by conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other mode of ratification may be proposed by the Congress; provided that no amendment which may be made prior to the year one thousand eight hundred and eight shall in any manner affect the first and fourth clauses in the ninth section of the first article; and that no state, without its consent, shall be deprived of its equal suffrage in the Senate.

The second method listed, the calling of a convention upon the application of two-thirds of the states, has never been invoked under our current system. For an examination, and more history, read here.

Thirty-four states (two-thirds) are needed to force Congress to call such a convention. As of the beginning of 2016, 27 states had live applications for a constitutional convention, or Con-Con, so only seven more were needed. This year West Virginia and Oklahoma signed on, bringing the total to 29, leaving only five states to capture.

In March, an application for a BBA convention passed the West Virginia House and Senate. Oklahoma followed in April with its House of Representatives and Senate reversing last year’s defeat of a Con-Con application by passing a resolution “making two separate applications to the United States Congress to call a convention of the states under Article V of the United States Constitution.” One of these applications asked Congress to call a “convention of the states” for the purpose of proposing a BBA.

With Delaware’s passage of a rescission bill in May, the total is now reduced by one, with 28 states now on board with “live” applications for a BBA Con-Con — with six more needed to trigger a call. Still too close for comfort for Con-Con opponents.

Touted as the panacea for all political problems, Article V, according to proponents, “puts the states back in power.” The elephant in the room, remaining unaddressed by those in favor of a Con-Con, is that the states’ participation in such a convention ends at making the request. Congress will still remain at the helm in deciding how delegates are selected, when and where and how a convention will be conducted, and the method of ratification to be used. Proponents argue that the measure will return Congress to its constitutional boundaries, restore republican government, and rein in federal overreach. Having never been used under our current system, though, the Article V convention process is untested and undefined.

In the minds of opponents however, the movement is revealed to be a false solution. Inherent in the process is the fact that the same congressional body that is currently ignoring its constitutional boundaries will likely continue ignoring the boundaries of future amendments. So, assuming an expensive, time-consuming, and flawed procedure is accomplished, we might be worse off than before — with the added risk that the current Constitution, as abused as it is, could be obliterated altogether.

Texas, considered a crucial state in the fight for a Con-Con, convenes its biennial legislature in January 2017. While having defeated a Con-Con bill in the 2015 session, the Lone Star State still has open calls, including one dating back to 1899, and a new governor, Greg Abbott, who’s gone on record as being in favor of a convention. Opponents of a Con-Con in the South, who depend on what Texas does, bemoan that such a big state has been unable to completely kill the measure, while a tiny northern state has scored a huge victory. Kudos to Delaware.

On the upside, the Constitution provides hope through the 10th Amendment. Rather than the costly and risky battle over a Con-Con, it bears mentioning that the states can take back their power by adhering to their duties of simply ignoring unconstitutional federal laws. Many states are already successfully doing this. Seems a lot easier to just invoke the 10th Amendment, called, rightfully so, the “rightful remedy.” For more information on the how nullification of unconstitutional laws under the 10th Amendment is a better solution than revising the Constitution with an Article V constitutional convention, see “Nullification vs. Constitutional Convention: How to Save Our Republic.”

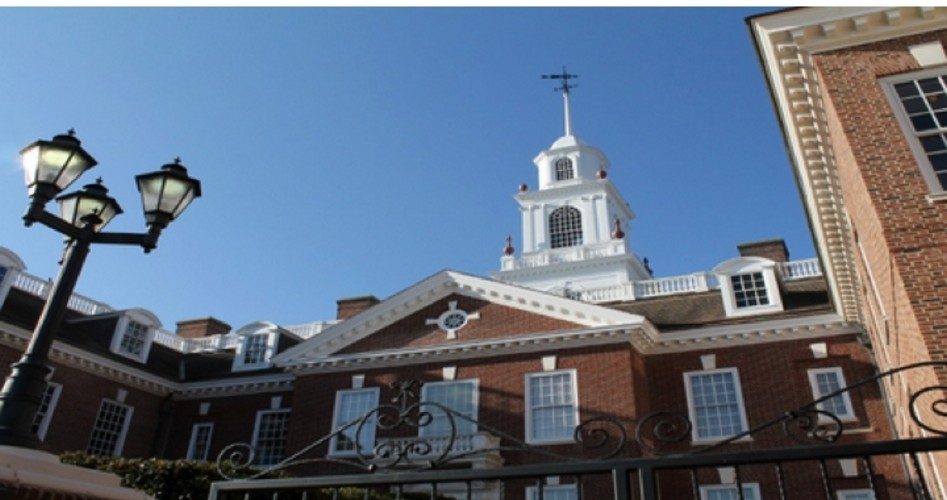

Photo of Delaware General Assembly