The 9th District Court of Appeals ruled two to one on September 4 that innocent people thrown into prison on material witness pretexts can sue former Attorney General John Ashcroft for losses.

"We find this to be repugnant to the Constitution and a painful reminder of some of the most ignominious chapters of our national history," Judge Milan D. Smith Jr. wrote. He added that “we hold that Ashcroft’s policy as alleged was unconstitutional.”

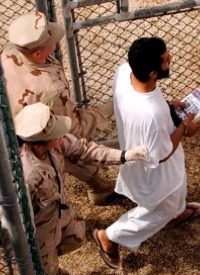

Attorney General Ashcroft’s policy was to detain people — including many innocent American citizens — solely for questioning, throwing them in prison leg-irons using the pretext of calling them “material witnesses.” Ashcroft did this even in cases where those American citizens willingly told officials what they knew, as was the case with Abdullah al-Kidd, a native American citizen and former University of Idaho football player who had converted to Islam and had won a full scholarship to a major Saudi Arabian university. The court described what happened:

Abdullah al-Kidd (al-Kidd), a United States citizen and a married man with two children, was arrested at a Dulles International Airport ticket counter. He was handcuffed, taken to the airport’s police substation, and interrogated. Over the next sixteen days, he was confined in high security cells lit twenty-four hours a day in Virginia, Oklahoma, and then Idaho, during which he was strip searched on multiple occasions. Each time he was transferred to a different facility, al-Kidd was handcuffed and shackled about his wrists, legs, and waist. He was eventually released from custody by court order, on the conditions that he live with his wife and in-laws in Nevada, limit his travel to Nevada and three other states, surrender his travel documents, regularly report to a probation officer, and consent to home visits throughout the period of supervision. By the time al-Kidd’s confinement and supervision ended, fifteen months after his arrest, al-Kidd had been fired from his job as an employee of a government contractor because he was denied a security clearance due to his arrest, and had separated from his wife. He has been unable to obtain steady employment since his arrest.

Remember, nobody ever accused al-Kidd (who was of African-American descent) with committing a crime, and there was no evidence he ever did anything improper. In fact, the court noted that he had willingly talked with the FBI whenever they had questioned him before his arrest. Yet al-Kidd was subjected to 16 days of strip searches and detention, followed by 15 months of house arrest. But al-Kidd did have a passing acquaintance with Sami Omar Al-Hussayen through the University of Idaho (where Al-Hussayen was a graduate computer science student), someone the FBI was investigating. So was Al-Hussayen a terrorist, and al-Kidd linked to a terrorist? No. The FBI did eventually claim Sami Omar Al-Hussayen ran a “jihadist” website, but it turned out to only be the Islamic Assembly of North America website, a mainstream site that has since become all but defunct. The FBI eventually indicted Al-Hussayen, an immigrant, for visa fraud and making false statements to U.S. Officials, but U.S. juries acquitted Al-Hussayen.

Sworn FBI statements at the time of al-Kidd’s abduction (it cannot legally be called an “arrest,” as no charges against him were ever filed) state that al-Kidd had obtained $20,000 in cash from Al-Hussayen and that al-Kidd had purchased a one-way first class ticket to Saudi Arabia for $5,000 in order to avoid testifying in Al-Hussayen’s case. Both statements proved to be false. Al-Hussayen had not given al-Kidd money, and al-Kidd had purchased a round-trip coach ticket to Saudi Arabia to attend university there for $1,700.

But the Aschcroft-run Justice Department under the Bush administration was politically vested in the detention of this American citizen without trial. FBI Director Robert S. Mueller testified before the House Appropriations Committee on March 27, 2003 about the FBI’s upcoming budget. At the top of Mueller’s list of “victories” was the unconstitutional detention of this American citizen without trial or indictment:

The prevention of another terrorist attack remains the FBI’s top priority. We are thoroughly committed to identifying and dismantling terrorist networks, and I am pleased to report that our efforts have yielded major successes over the past 17 months. Over 212 suspected terrorists have been charged with crimes, 108 of whom have been convicted to date. Some are well-known — including Zacarias Moussaoui, John Walker Lindh and Richard Reid. But, let me give you just a few recent examples…. On March 16, Abdullah al-Kidd, a US native and former University of Idaho football player, was arrested by the FBI at Dulles International Airport en route to Saudi Arabia. The FBI arrested three other men in the Idaho probe in recent weeks. And the FBI is examining links between the Idaho men and purported charities and individuals in six other jurisdictions across the country. [Emphasis added]

Mueller was only following orders in detaining American citizens without trial, not that it justifies Mueller’s conduct. Again, al-Kidd was never charged with a crime and was never charged with even knowing any terrorists. Ashcroft had announced new policies on October 31, 2001 where the federal government would begin imprisoning “material witnesses,” and it was inaugurated with a press release:

Today, I am announcing several steps that we are taking to enhance our ability to protect the United States from the threat of terrorist aliens. These measures form one part of the department’s strategy to prevent terrorist attacks by taking suspected terrorists off the street…. Aggressive detention of lawbreakers and material witnesses is vital to preventing, disrupting or delaying new attacks.

The court summarized al-Kidd’s case: “al-Kidd alleges that he was arrested without probable cause pursuant to a general policy, designed and implemented by Ashcroft, whose programmatic purpose was not to secure testimony, but to investigate those detained.” Al-Kidd’s lawyers from the ACLU argued: “Ashcroft either knew or should have known the violations were occurring and did not act to correct the violations.”

And Ashcroft’s lawyers have not contested the facts; they have simply argued that Ashcroft was entitled to “absolute immunity” as Attorney General. In other words, Ashcroft’s attorneys argue that the Attorney General is above the law when he is in his official capacity, even when he is abusing the powers of his office to unconstitutionally oppress citizens. But the court ruled that “United States Attorney General is not entitled to absolute immunity in the performance of his or her ‘national security functions.’” The court continued:

What we do hold is that probable cause— including individualized suspicion of criminal wrongdoing — is required when 18 U.S.C. § 3144 is not being used for its stated purpose, but instead for the purpose of criminal investigation. We thus do not render the material witness statute “entirely superfluous,” dissent at 12339; it is only the misuse of the statute, resulting in the detention of a person without probable cause for purposes of criminal investigation, that is repugnant to the Fourth Amendment. All seizures of criminal suspects require probable cause of criminal activity. To use a material witness statute pretextually, in order to investigate or preemptively detain suspects without probable cause, is to violate the Fourth Amendment. [Emphasis in original]

The dissenting Judge Carlos T. Bea noted that the basic issue was: “can a prosecutor, empowered by law to arrest an individual for one declared purpose, be immune from suit when he arrests that person with another, secret purpose in mind? Our natural reaction is, ‘Of course not!’ Such a prosecutor is abusing the vast discretionary powers we have entrusted to him. He is not playing fair; he is playing ‘Gotcha!’ But under our law, that natural reaction would be wrong.” Bea agreed with the Ashcroft defense that the Attorney General had unlimited immunity, was completely immune from suit by his victims, and noted the lack of court precedent for limiting the immunity of an Attorney General who had misused his official powers. But the deciding Judge Milan D. Smith, Jr. wrote that the lack of a precedent was due to the fact that no Attorney General had ever so brazenly claimed immunity in such a corrupt fashion before. The lack of a precedent, Smith noted, was “due more to the obviousness of the illegality than the novelty of the legal issue.”

Ashcroft’s decision to detain Americans for questioning using the “material witness” pretext is a clear violation of the Fifth Amendment right against imprisonment without due process of law and the Fourth Amendment’s search and seizure provisions. The court rightly concluded:

We are confident that, in light of the experience of the American colonists with the abuses of the British Crown, the Framers of our Constitution would have disapproved of the arrest, detention, and harsh confinement of a United States citizen as a “material witness” under the circumstances, and for the immediate purpose alleged, in al-Kidd’s complaint. Sadly, however, even now, more than 217 years after the ratification of the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution, some confidently assert that the government has the power to arrest and detain or restrict American citizens for months on end, in sometimes primitive conditions, not because there is evidence that they have committed a crime, but merely because the government wishes to investigate them for possible wrongdoing, or to prevent them from having contact with others in the outside world. We find this to be repugnant to the Constitution, and a painful reminder of some of the most ignominious chapters of our national history.

Ashcroft and the other architects of policies that assaulted the U.S. Constitution’s Bill of Rights under the Bush administration must be held accountable for their crimes if the Constitution is to be preserved.

Photo: AP Images