A Pennsylvania health system is making a significant change in how it charges patients for procedures. Instead of sending them or their insurers a complex bill with dozens of different charges after the fact, St. Luke’s University Health Network is posting all-inclusive prices for common procedures on its website, then having patients pay in advance.

This is, of course, nothing unusual in other sectors of the economy; most businesses tell customers how much something will cost up front. In the healthcare sector, however, it’s something of a rarity because for the last several decades, the primary customer has been the insurance company, not the patient, so patients had little desire or need to see how much a procedure would cost in advance. In fact, patients who did try to find out how much things would cost were often given the runaround, as The New American reported this summer:

“I called local surgeons and facilities to ask for hernia surgery costs, and never received a firm price, or complete information about what was actually done,” said Bob Singleton of Dallas, Texas. “The verbal estimates (they wouldn’t put them in writing) were in the $5k to $8k range, and that was after their ‘discount’ for cash payment, which was 5 percent.”

Some small, independent physicians’ groups such as the Surgery Center of Oklahoma (profiled in the above-linked story) have been offering up-front pricing for years. St. Luke’s, on the other hand, has a network of six hospitals and over 200 medical centers in Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

“We believe we are the first full service hospital and health system in the nation to offer this type of price transparency program,” Joel Fagerstrom, executive vice president and chief operating officer of St. Luke’s, said in a press release announcing the program.

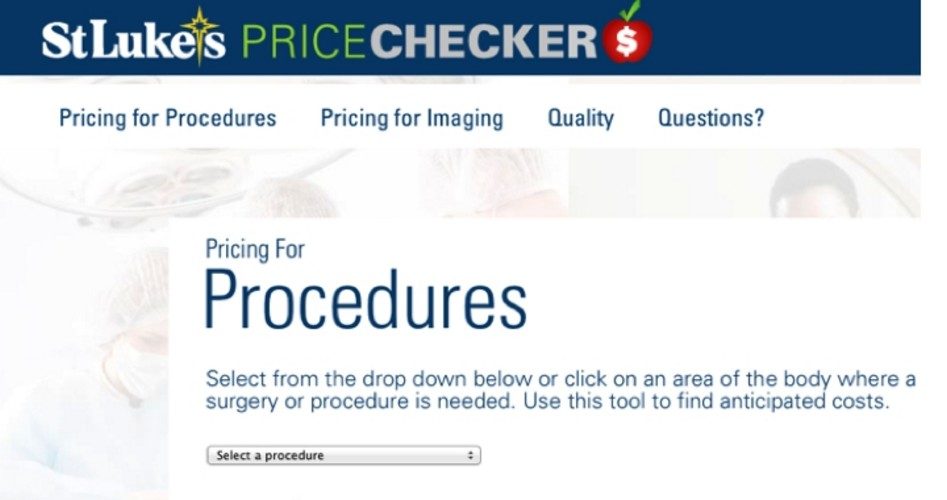

Visitors to St. Luke’s PriceChecker website can select from lists of common procedures, each one displaying the price, which includes the cost of the operating room, physician, imaging and analysis, anesthesia, and post-op doctor’s office visit. There are similar lists for imaging tests, the prices of which include both the study and the radiologist’s reading and reporting of it.

Once the patient completes an online form indicating which procedure he wishes to undergo, a St. Luke’s “navigator” will be in touch with him. According to the Express-Times of Easton, Pennsylvania, navigators “can help patients understand their payment obligations, navigate other financial resources that may be available and investigate various payment options, officials said.”

Although the bundled price covers the majority of the costs of a procedure, patients could still incur additional costs if, e.g., extra lab tests or procedures are needed. “A colonoscopy, for example, costs $1,050, but if the procedure finds cancer, the cost for treating the cancer is extra for the patients or their insurers,” noted the Hazleton, Pennsylvania, Standard-Speaker.

Why, after all these years of billing in the traditional fashion, did St. Luke’s decide to give patients the opportunity to prepay fixed prices for procedures?

For one thing, “the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services began posting average charges for 100 procedures at 3,300 American hospitals on its website two years ago,” wrote the Standard-Speaker.

More significant, however, is the fact that an increasing number of Americans are covered by high-deductible insurance plans, in large part because of ObamaCare, which is “unintentionally creating a consumer market,” as Dr. Keith Smith, CEO and managing partner of the Surgery Center of Oklahoma, told The New American. Since patients — whether they are covered by employer-based or exchange insurance — are now often paying their own way, they have a strong incentive to find the lowest-cost provider of the service they need. And with healthcare costs once again rising, that need is even more urgent.

“There’s really a pent-up demand for this,” St. Luke’s vice president for finance, Francine Botek, told the Express-Times. “With the migration to high-deductible health insurance plans, there is a greater need for a program like this, and we know there will be an even greater need in the future.”

The consumer market in healthcare inadvertently created by ObamaCare is therefore having some salutary effects. Unfortunately, those effects will be limited because the vast majority of the coverage growth under the healthcare law has come from its expansion of Medicaid, which gives its beneficiaries zero incentive to shop around (except for simply trying to find someone who will take their “insurance”). St. Luke’s program won’t apply to Medicare and Medicaid patients “because of limitations the government puts on health care providers,” explained Botek. It also won’t apply to the network’s facilities in New Jersey for the time being.

Still, anything that improves price transparency in any sector — but especially in one whose actual costs have been shrouded in negotiations between providers and insurers for so long — is an improvement. The best way to bring healthcare costs under control is not to impose price controls from Washington or heavily regulated insurance companies; it’s to make people responsible for the costs of their own care and then give them the information they need to make informed decisions about it.