“If you look for the bad in people, you will surely find it.” This quotation, generally attributed to Abe Lincoln, alludes to a simple truth: Everyone is a sinner — no one is perfect.

A corollary of this is that there’s no such thing as a “perfect” candidate (not literally speaking, anyway). Despite this, some people behave as if having the choice of only “the lesser of two evils,” as many put it, means they shouldn’t vote at all. But this is misguided, says a man who is something of an expert on evil.

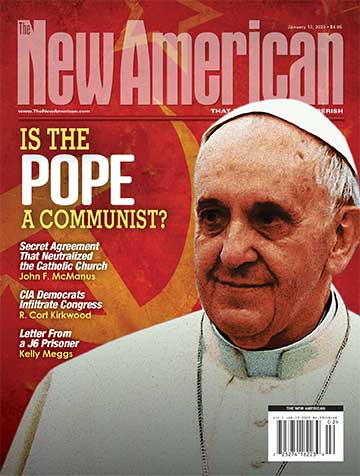

The counsel comes from Father Chad Ripperger. Aside from being a philosopher and theologian, Ripperger is also one of the Catholic Church’s most experienced exorcists. And, he says, the faithful actually have “an ‘obligation’ to vote for the lesser of two evils,” relates Breitbart. “However, that’s not the same as ‘voting for evil.’”

The Reasoning

Making his comments to hosts Jesse Romero and Terry Barber on Virgin Most Powerful Radio (VMPR), the clergyman elaborated:

And so people will say, “Well, yeah, but right now we’ve got, for example, candidates who are not perfect. One actually holds stuff that’s really evil, another guy holds stuff that’s also evil, but it’s not as bad,” etc….

Discussion of this has been reiterated throughout the history of the church, all the way up and through John Paul II had actually talked about it. So, but the basic principle is, in a situation like that, then your obligation is to vote for the lesser of two evils.

And the reason being is because, um, in the lesser of two evils, people say, “Well, you’re voting for evil.” No, actually, you’re not voting for evil. When you’re voting for a lesser evil, you’re not voting for the person’s evil or for the evil that the thing is doing. What you’re voting to is to preserve the good that would be lost if the other opponent got in, who’s more evil, or if the legislation got passed, which was actually even worse, or what have you.

Ripperger then said that failing to vote to preserve what good exists — and enabling a more evil person’s empowerment — is “negligence.” By this, he’s referencing what in theology is called “a sin of omission.” This is something you should have done, but didn’t (video below).

Sinister Semantics?

As with how phraseology influences polling results, however, much of this just has to do with wording. Consider: Asking “Should you vote for the lesser of two evils?” will inspire a certain number of nays. Asking, though, “Should you vote for the candidate who would ‘do more good’?” will evoke a more positive response. Yet both are substantively the same question. Only, one frames the matter negatively, the other positively.

Yet it’s not surprising that people focus on the negative. As an example, just imagine that 85 percent of a given candidate’s policy positions would please us. We may not know about, however (or remember), 80 percent of that 85 percent. It’s what sticks out like a sore thumb that attracts our attention. And what sticks out is generally what the media focus on — or what we disagree with passionately.

The epitome of such a candidate is Donald Trump. His policy accomplishments are many and quite “middle-of-the-road,” as is said. But how many Americans know of most of them? Attracting their attention are the eye-catching things he tweets and says — which are often magnified by media.

Imperfection Reigns

But this raises a point: Is it not generally imperfection itself that explains people’s reluctance to vote for the imperfect? That is, the decision to not vote (or support a fruitless third-party effort) is seldom a rational one. It’s usually an emotional reaction. Yet “The heart is deceitful above all things,” the Bible instructs. And as Ben Franklin warned, “Passion governs, and she never governs wisely.” Emotion has its place — but that place isn’t to supplant the decision-making role of the head.

As to rationality, a commenter under the above YouTube video illustrated the “perfect as enemy of the good” folly well. “I’m curious what people think: what if Catholics refused to vote until they found the perfect candidate?” he asked.

“My guess is that politicians would just stop representing Catholics” (or whatever the group in question is).

Built Into the System

There’s an irony here, too. Our system of government, our many checks and balances, are predicated on the reality that leaders will be highly flawed. As “Father of the Constitution” James Madison put it, “If Men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”

No one is truly worthy to be a parent, teacher, counselor, mentor, therapist, spiritual advisor, or clergyman — or leader. But somebody has to be. And we have only flawed humans to choose among.

Really, pondering this brings to mind an old Star Trek episode. Titled “The Changeling,” it involves an uber-powerful, artificially intelligent Earth probe that, after a deep-space accident, came to conclude that its mission was to cleanse the Universe of imperfection. The danger this posed to flawed human beings is obvious. Fortunately, after Captain Kirk cleverly made the automaton realize that it, too, was imperfect, it dutifully destroyed itself.

Sadly, our demand for perfection, or even figurative perfection, can also be suicidal. Remember, allowing, through inaction, evil to prevail is evil itself.