On Thursday, October 24, 1907, Wall Street was in turmoil. Crowds of spectators gathered to watch panicked bankers and their lackeys rushing about, desperately trying to halt the financial hemorrhaging of what would be known in the history books as the Panic of 1907. Outside one troubled bank, the Trust Company of America — where J. P. Morgan himself worked frantically behind the scenes to keep the institution solvent — long lines of angry depositors waited, hands jammed in pockets in the chill autumn air, to retrieve their deposited monies. No one knew whether the beleaguered bank, which Morgan had declared to be “the place to stop the trouble,” would have enough funds to survive the run.

No one paid attention to a poorly dressed 16-year-old boy standing in line with anxious depositors. He was small and slight of build, although his outsized coat concealed a back scarred by knife wounds from various street fights on the mean streets of Brooklyn. A stranger to the world of frock coats, silk hats, and high finance, young Sidney Weinberg had one thing in common with the men in suits milling about: he was on Wall Street to make money.

And make money he did, waiting in line for long stretches until he drew near to the bank doors, and then selling his place in line to some desperate depositor wanting to get to the cashier’s window to retrieve his life savings. Weinberg charged five dollars for his place, and then went to the back of the line to start over.

For several days, while the contagion of panic ran its course, Weinberg stood in line in front of the Trust Company of America, selling places in line to the desperate while the titans of finance met behind closed doors to bring the crisis under control. In the end, J.P. Morgan and his associates tamed the panic, and Sidney Weinberg, flush with new cash, skipped school for an entire week.

The activities of a truant schoolboy may have had more impact on the financial history of the United States than the deal-making of the Morgans and Rockefellers during the panic. Weinberg was expelled from school for truancy the following month, and returned to Wall Street to look for a job. He found custodial work at the then-middle tier investment firm, Goldman Sachs, and spent the rest of his life on Wall Street. It was Weinberg who turned Goldman Sachs into one of America’s most powerful investment banks and who, perhaps more importantly, used the resources of Goldman Sachs and his own considerable charisma to set up a collusive bond between Wall Street and Washington that persists to this day. The modern Goldman Sachs — one of the biggest players in the ongoing financial and economic turmoil — has become, thanks to the leadership of Weinberg and his successors, the very model of politically connected, taxpayer-guaranteed high finance.

Goldman Sachs Gets Going

Marcus Goldman, the founder of what would become Goldman Sachs in 1869, probably had no grand designs for a firm that got its start buying and selling commercial paper. Goldman, a European émigré who had come to the New World in 1848 to escape the chaos engendered by continent-wide revolutions in Europe, started his American career as a peddler in Philadelphia. After moving to New York, he brought a son-in-law, Samuel Sachs, into his firm, and Goldman Sachs & Co. was born.

During the Gilded Age, Goldman Sachs grew into a respectable player on Wall Street, but was overshadowed by the likes of J. P. Morgan and Kuhn Loeb, which enjoyed a corner on the then-lucrative business of underwriting stock and bond issues for railroads. This forced Henry Goldman, son of Marcus, to seek more creative financing opportunities. It was Goldman who conceived the notion that not only capital assets but also earning power could be used as a basis for financing. While this allowed Goldman Sachs to become involved in a greater variety of corporate ventures, like mercantile companies — which typically had little in the way of capital assets to serve as collateral but strong potential earning power — it also made confidence and investor perception much more critical to deal making and overall market strength. One of the first such major deals, the underwriting of a stock issue by United Cigar in conjunction with Lehman Brothers in 1906, left the two investment banks with 45,000 shares of preferred stock and 30,000 shares of common. The shares were resold to investors for a 24 percent markup. Goldman Sachs kept 7,500 shares as part of their compensation, giving the investment bank considerable leverage over the cigar company whose shares it had helped to float.

It must be borne in mind that all such activities were carried out under essentially free-market conditions. Well into the 20th century, Wall Street was still a bastion of laissez-faire capitalism, with the federal government declining to inject its unwelcome influence into the activities of investors, bankers, and entrepreneurs.

All of that began to change with the First World War, however. The war brought the first of several major setbacks to Goldman Sachs with the departure of its helmsman and chief financial innovator, Henry Goldman. Goldman was a public supporter of the German cause, and refused to temper his opinions when the United States entered the war in 1917. Goldman was finally forced to leave the firm, leaving a power vacuum that would eventually be filled by the upwardly mobile Sidney Weinberg.

Weinberg made partner in 1927, in the midst of the asset bubble of the Roaring Twenties. He was tasked with running the investment trusts division alongside Waddill Catchings, a flamboyant lawyer who was determined to take advantage of the fantastic run-up in stock prices by leveraging Goldman Sachs to the gills. When the stock market imploded in October 1929, so did Goldman Sachs’ share prices, swooning from more than $300 a share to about $2. The catastrophe nearly destroyed Goldman Sachs; as a last-ditch effort, Sidney Weinberg, one-time janitor’s assistant and mail-room worker, was promoted to senior partner and then to head of the firm in 1930.

Against all odds, Weinberg was able not only to salvage Goldman Sachs but to build it into a veritable financial empire. But he did it by helping to inaugurate the era of public-private Wall Street-Washington cronyism that continues to our day, and in which Goldman Sachs is still one of the preeminent players.

Prior to the Great Depression, the culture on Wall Street was still overwhelmingly free market-oriented, at least in comparison with today’s attitudes. The gigantic bailouts and flagrant favoritism for Wall Street fat cats that have disfigured recent American history were largely unknown and unwanted in the freewheeling days before the New Deal. When a newly elected FDR tried to fasten regulatory clamps on Wall Street, he met with stiff resistance. Fortunately for FDR, he found one man on Wall Street who was happy to play ball with the federal government, and to corral his fellow financiers into cooperating with the President’s grand new schemes: Sidney Weinberg.

Partnering With Politicians

Weinberg had first dabbled in presidential politics in 1932 as a member of the Democratic Party’s National Campaign Finance Committee, where he raised astronomical sums on FDR’s behalf. In 1933, he was appointed by the President to organize the Business Advisory and Planning Council, which became, as FDR intended, the liaison between the business community and the White House during the Depression. While such a thing might seem short of momentous in a modern world where the federal government is intimately involved in almost every aspect of American business, it was nothing less than revolutionary in the 1930s, when many Americans, including businessmen, regarded with horror the prospect of a federal government nationalizing industry and finance.

For that is what FDR intended to do, and with the help of Weinberg — whom he affectionately nicknamed “the politician” for his uncanny ability to soothe hackles and convert businessmen to the utopian cause of the New Deal — he managed to impose all manner of unprecedented controls and regimentation on the American free market. In this way, Sidney Weinberg, and by extension Goldman Sachs, was a central Wall Street figure in the first great Washington crusade against the free market. Under Weinberg, Goldman Sachs was one of the first Wall Street firms to become in effect a partner with the federal government, serving the interests of political insiders as much as the markets.

Weinberg was instrumental in helping to set up the Stock Market Board, the pred-ecessor to the Securities and Exchange Commission. During the war years, Weinberg, who believed that “government service is the highest form of citizenship,” was appointed assistant to the chair of FDR’s War Production Board, which sought to enlist every American businessman in the war effort and to mobilize every cent of private capital to serve the ends of the state. The indefatigable Weinberg called personally on nearly every major CEO in America to press them into the service of the federal government. According to historian Charles Ellis, whose recent book, The Partnership: The Making of Goldman Sachs, is the definitive work on the firm, Weinberg minced no words with the captains of industry and finance:

Our nation is in grave danger [Weinberg told them]. America needs an enormous number of talented executive leaders to organize a massive war production effort. The President has sent me here to get your help in identifying your very best young men. We need the smartest young stars you’ve got. And don’t you even think of passing off older men or second-raters. I’m asking the same thing of every major company in the country, and I’ll be watching very closely how well your men do compared to the best young men from all the other corporations.

In the face of such bullying, small wonder that most of American Big Business knuckled under to what can only be styled wartime fascism (though in private, they referred to Weinberg as “the body snatcher” for his ability to pluck away the best and the brightest from the private sector and put them to work for the wartime government). Nor was Weinberg slow to take personal advantage of the situation; after the war, many of these recruits, returning to the private sector (such as it remained) turned to Weinberg and Goldman Sachs for investment services, greatly raising the profile of the firm in the new public-private postwar business environment. The formula worked so well that Weinberg reprised his role of corporate “body snatcher” during the Korean War.

Sidney Weinberg also had a seedier side, matching a titanic work ethic and world-class ambition with a willingness to descend into unseemly conduct, often to serve the ends of the firm. He was a noted vulgarian, fond of dirty jokes, pranks, and ribald language. On one occasion, after a popular Washington, D.C., brothel was closed down by authorities, Weinberg had cards printed up and passed out that purported to give the phone number of the newly reopened house of ill repute; the number belonged to a friend of his in high finance. During the war, Weinberg worked on FDR’s Industry Advisory Committee under one Donald Nelson, a former Sears Roebuck executive. Part of his duties included, according to Ellis, “arranging the presence of attractive young women — the Miss Indianas and the Miss Ohios for whom Nelson had such an enormous appetite that the FBI worried that the Germans might figure it out and plant some of their female spies in Nelson’s bedchamber.” In one episode worthy of Hollywood film noir, an investment banker “who was there” told Ellis:

After making a lot of money going public with his own company, a corporate raider noticed that Baldwin United was selling at a very cheap price. So he took a big position and was going to offer to buy the rest of the stock at a price well above the market…. Takeover defense is something Goldman Sachs specialized in, so the firm was asked to help. Nobody was sure what to do, so Weinberg was asked for suggestions…. A little later, he told a young banker to call a particular guy. A meeting was arranged at Gage & Tolner’s restaurant in Brooklyn.

Weinberg’s man, wearing a black suit, black shirt, and a black string tie, came to the table and sat down, saying, “The only reason I’m here is I owe Weinberg.” After a brief explanation, the man in black said he would see what he could do…. Finally, he called to say, “We’ve got him. It’ll cost a hundred dollars — fifty dollars for a photographer and fifty dollars for the bellboy. He’s got a cutie holed up in a midtown hotel.”

A week later, the man in black called on the corporate raider and respectfully said to him, “You believe in this free country and so do I. Anybody can buy anything in this wonderful free country.” Then he started spreading the pictures from the hotel on the man’s desk, and said, “You can buy almost anything. But don’t do Baldwin or these could show up in the New York Post.” Then he excused himself and left. Nothing happened to Baldwin United, and nothing was printed in the newspapers.

Politically, Weinberg was something of a chameleon, supporting FDR for two terms but then switching his allegiance to establishment Republican Wendell Willkie in 1940. He was a friend and advisor to Eisenhower, Truman, and Kennedy, and by late in life had attained the same oracular status that Bernard Baruch enjoyed in an earlier generation, and that Warren Buffett enjoys in ours.

Despite his willingness to accommodate the vices of others, Weinberg led an unpretentious, even Spartan life, living in a modest home and using public transportation to commute to work. He was motivated less by money than by power and influence; by the end of his life, the man who had been a confidant of Presidents and captains of industry and had sat on dozens of corporate boards had amassed the comparatively modest fortune of only $5 million.

Sidney Weinberg was one of the leading architects of the postwar economic order, in which the federal government, no longer a neutral referee, was fully immersed in the goings-on of big business and high finance. The firm that Weinberg built into a financial superpower and on whose institutional culture he left an indelible mark has become, in the four decades since his passing, the preeminent player in the Wall Street-Washington spoils game.

Political Profits

Perhaps the privileged perspective of the new Goldman Sachs was best exemplified in 1995, when the Clinton administration, over howls of protest from Congress and from the voting public (who had just delivered a resounding electoral rebuke to the Clintons and the Democratic Party), rode to the rescue of the beleaguered Mexican economy, using funds from the little-known Exchange Stabilization Fund to send $20 billion to Mexico to bail out Mexican treasury bonds. The infamous Mexican bailout was an end run around Congress, using monies conveniently under the control of the executive branch, squirreled away in a fund created in the 1930s primarily to help shore up the unreliable Mexican peso. Adding to the outrage was the fact that Goldman Sachs held $5 billion in endangered Mexican bonds, and the man within the Clinton administration who lobbied most fiercely for the bailout was Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin, a former co-chairman of Goldman Sachs. Despite the flagrant conflict of interest (not to mention blatant unconstitutionality) of the Mexican bailout, none of the parties involved were ever prosecuted. Robert Rubin (whom President Clinton grandiosely styled the greatest Secretary of the Treasury since Alexander Hamilton) subsequently served an eight-year stint with Citigroup, and is currently an economic advisor to President Obama and co-chairman of the ultimate insider club, the New York-based Council on Foreign Relations.

The silky Rubin is far from the only Washington insider to have been plucked from the hallowed halls of Goldman Sachs. Another Treasury Secretary, Henry Paulson, architect of the Bush bailout, was a Goldman Sachs CEO (yet another Treasury Secretary, Henry Fowler, became a partner in the firm after his stint at Treasury in the 1960s). Another Goldman Sachs chairman, Jon Corzine, went on to become a U.S. Senator and Governor of the state of New Jersey. Robert Zoellick, former U.S. Trade Representative and Deputy Secretary of State and now World Bank president and prominent member of the Council on Foreign Relations, was a managing director at Goldman Sachs. Joshua Bolten, another former Goldman employee, was White House Chief of Staff for President George W. Bush; it was Bolten who encouraged the President to pick Henry Paulson to head the Treasury Department late in the Bush presidency.

The Obama administration has recruited former top Goldman Sachs operatives Robert Hormats, Mark Patterson, Adam Storch, and Gary Gensler, and for top economic posts has appointed men with long financial ties to Goldman Sachs, such as Timothy Geithner, Lawrence Summers, and Gene Sperling.

Internationally, Goldman Sachs has left its mark as well. Romano Prodi, twice the Prime Minister of Italy and also the President of the European Commission for five years, was on the Goldman Sachs payroll in the early ’90s and again in 1997. (Indeed, as British journalist Ambrose Evans-Pritchard reported in 2007, many Italians believe Goldman Sachs controls their country outright, given that, in addition to Prodi, Mario Draghi, the governor of the Bank of Italy, and Massimo Tononi, Italian Deputy Treasury Chief until 2008, had ties to the firm.) Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of Canada, worked at Goldman Sachs for 13 years, eventually becoming managing director. Michael Cohrs, head of global banking at Deutsche Bank, is a Goldman product, as is Malcolm Turnbull, a prominent Australian politician and former chair of Goldman Sachs Australia.

There is, of course, nothing amiss in finding and hiring the best talent, as Goldman Sachs has almost unerringly done for decades. Sidney Weinberg and most of his successors have successfully brought many of the brightest minds in finance to Goldman Sachs and perpetuated a corporate culture that has always placed heavy emphasis on satisfying clients’ wants. Goldman Sachs has been an extraordinary innovator in finance, pioneering and refining the use of such latter-day financial staples as block trades and derivatives. But Goldman Sachs has never scrupled to pass up opportunities to exploit its connections in the political establishment, both nationally and abroad, as the sordid Mexican bailout amply demonstrated.

More recently, the world has been convulsed by the worst financial and economic crisis since the Great Depression, and Goldman Sachs has been at the center of the action. Lehman Brothers, one of Goldman Sachs’ biggest rivals, was the first domino to fall in the panic of 2008, with the federal government, led by Treasury’s Henry Paulson, refusing to give the storied investment bank a bailout. In the wake of Lehman’s bankruptcy, Ellis tells us, some on Wall Street believed that “Paulson … let Lehman Brothers fail in order to take out a competitor of his old firm, Goldman Sachs.” But, Ellis hastens to reassure his readers, the former Goldman Sachs chairman-turned-Treasury Secretary was in fact merely acting in the best interests of the nation, responding to public outrage over the prospect of a yet another taxpayer-funded bailout of Wall Street plutocrats.

Reassuring as Ellis’ claims might sound, they are belied by the subsequent actions of the U.S. government. Having cut Lehman Brothers loose, Washington deal-makers proceeded to loot American taxpayers anyway to save Goldman Sachs and a number of other financials deemed too big (or, more accurately, too well-connected) to fail. The first step was to re-charter Goldman Sachs (and its ailing competitor, Morgan Stanley) as a commercial bank. This in itself was not necessarily an ill; the noxious Depression-era Glass Steagall Act, which forbade individual financial institutions from carrying out both commercial banking and investment banking activities, had been repealed in 1999. But the motive for the change was to give Goldman Sachs, as a commercial bank, untrammeled access to Federal Reserve lines of credit. The financial wizards at Goldman lost no time re-arranging their assets to configure Goldman Sachs along the lines of a commercial bank holding company, and the deed was done. An additional infusion of liquidity came from no less an eminence than Warren Buffett, which should have been more than sufficient to keep Goldman Sachs afloat. But when TARP monies were doled out, Goldman Sachs received a $10 billion piece of the cake.

In the wake of the crisis, Goldman Sachs has emerged stronger than ever, and with a significant competitive advantage, thanks to the loss of Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, Salomon Brothers, Smith Barney, and Bear Stearns as independent investment banks. Despite new accusations from the SEC that Goldman Sachs defrauded investors by shorting its own investments in subprime mortgages, and allegations that the firm helped Greece to conceal its fiscal weaknesses with creative accounting when the Mediterranean country first applied for membership in the EU, it is unlikely — given Goldman’s heft in Washington and governments abroad — that any such charges will stick.

Thanks to the corporate culture instilled by Sidney Weinberg, leadership at Goldman Sachs sees nothing amiss in its many ties with the political powers that be. “The vitriol toward Wall Street,” observed current Goldman Sachs CEO and chairman Lloyd Blankfein, “casts a pall over our industry, including Goldman Sachs. It’s ironic that our longstanding tradition of public service is now so misunderstood in Washington and in the media. It’s almost been turned on its head — a virtue turned into a vice. That weighs heavily on the people of Goldman Sachs, who care deeply about the quality of their work and contributions and how those are perceived. Reputation counts for a lot in this business.” Thus are the many politically motivated sins of Goldman Sachs, including complicity in the Mexican bailout and in the more recent financial catastrophe, recast as “public service.”

The 20th century was a time of extraordinary advances in finance, with the development of a bewildering array of new investment vehicles all calculated to ease the flow of capital and facilitate economic growth all over the world. There is a conspicuous tendency to vilify the wealthy and the successful for alleged greed, including brilliant financial innovators like Goldman Sachs. But such accusations amount to repudiation of free-market capitalism, which is one of the grossest errors of our age. Where mega-financials like Goldman Sachs are culpable is in seeking to take control of the political process, soliciting preferential treatment (like bailouts) and participating in what has become — thanks to the worldwide regime of fiat money — a gigantic financial Ponzi scheme, in which central banks pour newly created money into the coffers of money-center banks and investment houses and inflate asset bubbles that enrich the well-connected to the detriment of everyone else.

There can be no doubt that Goldman owes its uncanny success as much to its political connections as to its financial acumen. As long as that remains the case, Goldman will doubtless remain on top, to the perplexity of those who fail to grasp the significance of the Goldman Sachs-D.C. pipeline. Only by restoring the wall of separation between Wall Street and Washington, forcing investment firms like Goldman Sachs to stand or fall on their own merits, can America’s financial sector shake off the taint of political cronyism that men like Sidney Weinberg were happy to encourage.

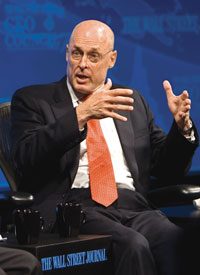

— Photo of former U.S. Treasury Secretary & Goldman Sachs head Henry Paulson: AP Images