Some of the opponents of the recently enacted health care legislation may have been premature with their warnings about "death panels." A death panel of sorts can be found in the Restoring American Financial Stability Act of 2010, the financial regulation bill that has Congress divided once again along partisan lines. The bill would establish in the U.S Bankruptcy Court in Delaware an ominous-sounding Orderly Liquidation Authority Panel to preside over the (presumably) orderly process of putting out of business a large bank or non-banking financial firm whose "financial distress or failure" could create "risks to the financial stability of the United States…"

Senator Richard Durbin (D-Ill.) cited the language of the bill to refute Republican claims that the bill, with its provision for a $50 billion "Orderly Liquidation Fund" — created by a tax on the financial firms — will result in more "bailouts" for firms deemed too big to fail. According to Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), the bill would "institutionalize" bailouts and require taxpayer funding when the Liquidation Fund runs out. As McConnell recalled, the bailout of AIG alone in 2008 was over three times the amount of the proposed Liquidation Fund.

That prompted Durbin to wonder aloud at a press conference on Thursday if McConnell "has read the bill, particularly if he has read the section between pages 110 and 295, which is entitled ‘Orderly Liquidation Authority.’ " Durbin went on to describe how a financially distressed or failing institution would be terminated.

"Liquidation is the end of the bank," he said, "not a bailout that it could continue in business… The management team is fired. The shareholders are wiped out. The firm’s assets are sold off to pay any firm debts. Once the money is gone, the creditors are wiped out. The taxpayers don’t pay for any part of this, and at the end of it, the company is gone. There is nothing to bail out."

No more company, no bailout. That seems clear. But why not let the bankruptcy laws already on the books be applied to the failing firms, rather than create a new Financial Stability Oversight Council and a separate Orderly Liquidation Authority Panel? The council will no doubt attempt to identify and deal with the distressed firms before their failure brings to fruition the aforementioned "risks to the financial stability of the United States." But critics of the bill say that liquidation of a firm under the proposed financial reform would be a bailout of its creditors.

"Recall that during the financial implosion of late 2008, Goldman (Sachs) was not bailed out directly by taxpayers, but instead received tax dollars as a creditor of AIG," wrote John Berlau of the Competitive Enterprise Institute. "Goldman received $12.9 billion in the "backdoor bailout" of AIG because of the credit default swaps it owned that AIG had insured. Goldman and other of AIG’s counterparties were paid by the government 100 cents on the dollar in this bailout, whereas creditors in bankruptcy court often get less than 50 cents on the dollar." Goldman Sachs is, of course, one of the nation’s largest investment firms, with a number of executives who have been in and out of high positions in government including former Treasury Secretaries Robert Rubin and Henry Paulson. And the firm’s executives and its political action committee are major contributors to political candidates of both the Democratic and Republican parties. But there are yet other examples of how favored companies and organizations benefit when Congress and the White House ride to the rescue of "distressed" firms and their creditors. Political analyst Michael Barone, reflecting on last year’s bailout of Chrysler, recalled "the Obama administration’s decision to force bondholders to accept 33 cents on the dollar on secured debts while giving United Auto Workers retirees 50 cents on the dollar on unsecured debts. This was a clear violation of the ordinary bankruptcy rule that secured creditors are fully paid off before unsecured creditors get anything. The politically connected UAW folk got preference over politically unconnected bondholders."

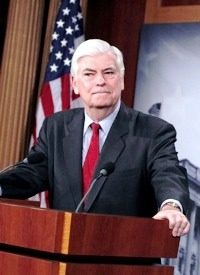

The bill’s sponsor, Sen. Christopher Dodd (D-Conn.) insists that Wall Street will bear all the costs of the new regulations and liquidations. "And middle class families on Main Street won’t have to pay a penny: the largest Wall Street firms will have to put up money for a $50 billion fund to cover the costs of liquidating the failed financial firm."

But the danger is that creditors will be more likely to lend to large financial firms involved in risky financial ventures if the federal government is standing behind them ready to pay off their debts. As Peter Wallison of the American Enterprise Institute put it, the law would create "Fannie Maes and Freddie Macs in every sector of the financial system where these large companies are designated for Fed regulation, including insurance companies, hedge funds, finance companies, bank holding companies, securities firms, and any other kind of financial institution the government wants to regulate. Since these firms will be too big to fail, they will be seen in the market-as Fannie and Freddie were seen-as ultimately backed by the government and thus safer firms to lend to than small firms that are not government backed." That would have the effect of consolidating markets into a few large competitors "operating under the benign supervision of the government," he said.

While most of the opposition to the financial reform bill has come from Republicans, Rep. Brad Sherman of California is one Democrat who believes there is less to the effort to "reform" Wall Street than meets the eye.

"The Dodd bill," said Sherman "has unlimited executive bailout authority. That’s something Wall Street desperately wants but doesn’t dare ask for."

Photo: Sen. Chris Dodd (and Sen. Mark Warner, D-Va., not shown) speak to reporters about financial reform on Wall Street during a news conference on Capitol Hill in Washington, April 19, 2010: AP Images