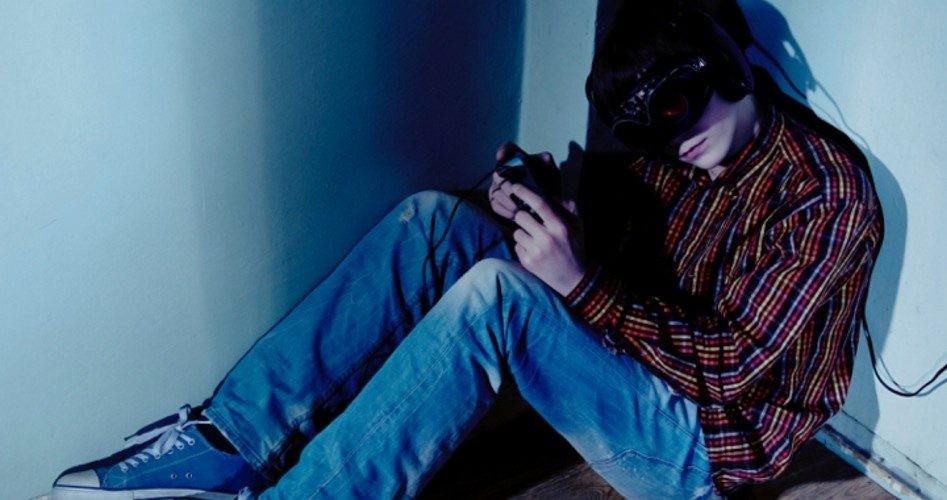

We’ve all witnessed the addiction: Not just adults, but kids, entranced by their phones-cum-computers, picking them up every chance they get. Studies show that children average 3.4 hours a day on electronic devices, while teens spend nearly nine hours daily imbibing media. But is this the problem it appears or just another old-fogey, Luddite-light concern?

Some contend the latter, as the Associated Press reports:

When Stephen Dennis was raising his two sons in the 1980s, he never heard the phrase “screen time,” nor did he worry much about the hours his kids spent with technology. When he bought an Apple II Plus computer, he considered it an investment in their future and encouraged them to use it as much as possible.

Boy, have things changed with his grandkids and their phones and their Snapchat, Instagram and Twitter.

“It almost seems like an addiction,” said Dennis, a retired homebuilder who lives in Bellevue, Washington. “In the old days you had a computer and you had a TV and you had a phone but none of them were linked to the outside world but the phone. You didn’t have this omnipresence of technology.”

Today’s grandparents may have fond memories of the “good old days,” but history tells us that adults have worried about their kids’ fascination with new-fangled entertainment and technology since the days of dime novels, radio, the first comic books and rock n’ roll.

“This whole idea that we even worry about what kids are doing is pretty much a 20th century thing,” said Katie Foss, a media studies professor at Middle Tennessee State University. But when it comes to screen time, she added, “all we are doing is reinventing the same concern we were having back in the ’50s.”

The AP then goes on to outline, and pooh-pooh, fears sparked by the advent of radio, television, and the early Internet. So what’s to worry? We’re all still here, right? It’s a very reassuring argument that many will want to believe — it’s also very deceptive.

What history really teaches is that up until modern times, outside influences often only entered your village, tribe, etc. with an invading force. Philosopher G.K. Chesterton pointed out that one great aspect of the Middle Ages is that everyone (in Europe) agreed on “what really mattered.” They didn’t have to worry about others telling their children homosexuality is a lifestyle choice, a boy masquerading as a girl is expression, or childhood disobedience is a legitimate exercise of freedom. Likewise, an isolated primitive tribe, no matter where, was united in its brand of primitiveness.

Yet insofar as influences were considered bad and perceived to be present, concern was evident. The ancient Greeks emphasized that the arts were so powerful they must be controlled, and philosopher Plato warned that changes in music could even influence government law. And do you think that exposing someone’s child to heresy — a concern not just in Christian cultures but also pagan ones, mind you — would be tolerated for a moment? Note that, rightly or wrongly, Greek thinker Socrates was executed in 399 B.C. for “mocking the gods” and “corrupting the young.”

It is true, though, that such concerns typified the 20th century, and for an obvious reason: Also typifying it was the newfound ability to rapidly disseminate information — and misinformation.

For most of history, communication was via the spoken word or the relatively few handwritten documents available (and most people were illiterate). Thus, generally, the only way someone could inculcate your child with “strange” ideas was to kidnap and raise him in an alien land. Yet communications-technology revolutions made it progressively easier for alien ideas to reach your child’s mind right in your home.

So, yes, every 20th-century generation of parents was worried about something, radio, TV, Internet , etc.

And every 20th-century generation of parents was correct.

While some portray them as having been technology-eschewing old fuddy-duddies, their critics are the ones behaving as one-dimensional simpletons. In reality, most people accepted the new tools technology birthed, but they also understood that all tools can be used for good or evil. And when the outside world suddenly has the capacity to invade your home in a new way, without an army, shouldn’t you be concerned about what will be fed into your children’s minds?

Some, such as Professor Foss, shrug this off when considering it in theory, but reality is clarified for them when their own philosophical ox is gored. As I wrote in 2013 in “Why the NRA Is Right about Hollywood”:

Sure, depending on our ideology, we may disagree on what entertainment is destructive, but that it can be destructive is something on which consensus exists. Just consider, for instance, that when James Cameron’s film Avatar was released, there was much talk in the conservative blogosphere about its containing environmentalist, anti-corporate and anti-American propaganda. At the other end of the spectrum, liberals wanted the old show Amos ‘n Andy taken off the air because it contained what they considered harmful stereotypes. Or think of how critics worried that Mel Gibson’s Passion of the Christ would stoke anti-Jewish sentiment or that Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ would inspire anti-Christian feelings, and how the Catholic League complained that The Da Vinci Code was anti-Catholic. Now, I’m not commenting on these claims’ validity. My only point is that when our own sacred cows are being slaughtered, few of us will say, “Well, yeah, the work attacks my cause, but I don’t care because it’s the values taught at home that really matter.”

(As to the last line, it should be mentioned, again, that modern communication devices do transmit “values” into your home.)

Media’s capacity to sway is why Adolf Hitler had his propaganda filmmaker, Leni Riefenstahl, and why all modern regimes have at times created their own propaganda films. It’s why conservatives are concerned about leftist indoctrination in schools and social-media and search-engine suppression of their views. It’s why social messages are put into children’s shows. It’s also why, even 25 years ago, hinterland youth far removed from any ghetto sometimes wore “gangsta’”-style baggy pants and why tattoos are defacing people now the world over. Internet and TV can spread fads, fallacies, and falsehoods like a disease.

Research has detected the effects of communication-tool misuse, too. As I also reported in 2013:

For instance, a definitive 1990s study published by The Journal of the American Medical Association found that in every society in which TV was introduced, there was an explosion in violent crime and murder within 15 years. As an example, TV had been banned in South Africa for internal security reasons until 1975, at which point the nation had a lower murder rate than other lands with similar demographics. The country’s legalization of TV prompted psychiatrist Dr. Brandon Centerwall to predict “that white South African homicide rates would double within 10 to 15 years after the introduction of television….” But he was wrong.

By 1987 they had more than doubled.

There’s also the work of Lieutenant Colonel David Grossman, a former West Point military psychologist and one of the world’s foremost experts on what he calls “killology.” He contends that the extreme violence viewed on TV and simulated video-game participatory violence amount to the kind of conditioning/desensitization used to inure soldiers to killing.

Then there’s the matter of why electronic devices are so addictive. As psychotherapist Dr. Nicholas Kardaras, executive director of The Dunes East Hampton and a former clinical professor at Stony Brook Medicine, wrote in 2016, “We now know that those iPads, smartphones and Xboxes are a form of digital drug. Recent brain imaging research is showing that they affect the brain’s frontal cortex — which controls executive functioning, including impulse control — in exactly the same way that cocaine does. Technology is so hyper-arousing that it raises dopamine levels — the feel-good neurotransmitter most involved in the addiction dynamic — as much as sex.”

None of this can be understood, of course, by viewing matters simplistically. Some will say “We can’t blame video games,” “We can’t blame TV,” etc. (but we can blame ourselves). The issue isn’t one factor in isolation, however, but a system in which a whole group of very powerful tools are frequently used to spread evil. Also irrelevant is the consideration of one person in isolation — i.e., “I used ______ and turned out okay” (of course, we all turned out “okay,” right?!). The issue is civilization’s overall cultural trajectory.

Also bear in mind that many hi-tech titans, such as Bill Gates and the late Steve Jobs, raised their children relatively tech free. There’s a lesson here. If a group of scientists created a supplement that they’d only give their own kids in infrequent small doses, would you give it to yours in continual large ones?

Photo: Slonov/E+/Getty Images